My first exposure to Archer Daniels Midland was during a campus recruiting event my senior year in college. Everything’s a little bit blurry in retrospect, but I clearly recall that the aged gentleman serving as a representative of ADM was missing a couple of fingers on his right hand. Maybe I’m making this up, but not intentionally: at one point in his presentation, indicating the stellar safety record at his plant, he held up his mangled appendage and said, “We’ve gone three years without a lost-time accident.” I wasn’t too disappointed when I wasn’t selected for an interview.

My first exposure to Archer Daniels Midland was during a campus recruiting event my senior year in college. Everything’s a little bit blurry in retrospect, but I clearly recall that the aged gentleman serving as a representative of ADM was missing a couple of fingers on his right hand. Maybe I’m making this up, but not intentionally: at one point in his presentation, indicating the stellar safety record at his plant, he held up his mangled appendage and said, “We’ve gone three years without a lost-time accident.” I wasn’t too disappointed when I wasn’t selected for an interview.

Upon graduation, a couple of my lab partners took jobs in Decatur (we’ve since fallen out of touch), and I accepted a position with a competing agribusiness company, Cargill. This was about the time that news was breaking of the price-fixing scandal which played out in The Informant!, and Cargill was trying to market itself as the friendly, honest alternative to ADM. During orientation, they made a big thing about the assertion that Cargill didn’t take bribes. I was clearly honored to work for a company with such high standards.

I’ve spent most of my so-called career on the fringes of ADM’s world, working for several of their competitors, but I’d never really known much more than hearsay about the operation of the company. I’d heard stuff like how they didn’t participate in any industry associations, how ADM stands for “Another Dead Man” because of their fairly callous attitude toward employee safety, and their reputation for cutthroat price-cutting to run out smaller competitors.

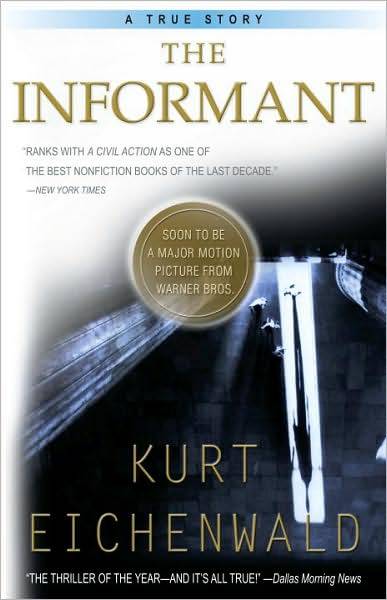

I figured that there’d never be a better opportunity for my actual work experiences to inform an article for Smile Politely than this particular moment in time. I recently read Kurt Eichenwald’s book, the less-exclamatorily titled The Informant, and then I watched the movie to bring things full-circle.

THE BOOK

THE BOOK

The blurbs on the back cover promised that The Informant reads like nonfiction Grisham, and I’m pretty sure that’s what Eichenwald was shooting for.

He takes a few dozen pages at the beginning of the book to lay out the history of ADM, with its chief executive, Dwayne Andreas. Andreas is a Zelig-like character in American politics (his campaign contribution to Richard Nixon ended up in the account of one of the Watergate burglars, and Hubert Humphrey was his son’s godfather), and he was able to parlay that influence into beneficial legislation for his company. That sets the tone of corporate entitlement that is prevalent at ADM in the book; no matter what they do, there’s an attitude that their lawyers and Washington connections will clean up the mess.

Eichenwald uses plenty of breathless, distracting foreshadowing, like “he had no idea of the events he was about to set into motion,” or “he had little doubt it would be needed later,” that wouldn’t be out of place in a pulpy thriller. Eichenwald also takes an incredulous tone, assuming that his readers would be shocked — SHOCKED — that corporate executives would break the law, have blatantly sexist conversations, and stab each other in the back at each and every opportunity.

However, the book shines as a law-enforcement procedural, as well as a look inside the warped mind of Mark Whitacre, the titular head of ADM’s Bioproducts division as well as a compulsive liar, thief, and wacky FBI informant. His deceptions start out as entertainingly daft, but become increasing pathetic as it becomes clear that Whitacre is mentally ill.

His lack of credibility also undermines the narrative of ADM as corporate criminal, placing more attention on the twists and turns of his increasingly unbelievable tales and less on the culture of “our competitors are our friends, and our customers are our enemies” that prevailed. ADM conspired to fix prices in lysine (manufactured by Whitacre’s division), citric acid, and possibly corn syrup, among other commodities.

It’s an incredibly detailed account of crimes and their ensuing investigation and prosecution that would never have seen the light of day without the lunatic at its center.

THE MOVIE

THE MOVIE

For all the weight that Eichenwald’s book tried to bring to the price-fixing scandal and the corporate culture at ADM, Steven Soderbergh’s movie takes every opportunity to lighten the mood. Matt Damon, fully inhabiting the role of Whitacre, conveys most of his personality through increasingly baffled gazes into space and non-sequitur-laced voiceover narration.

Everything is played for laughs, and sometimes rightfully so, as in the case of Whitacre narrating his surveillance recordings for the FBI. However, the ADM executives spend very little time on-screen, and are often depicted more as bumbling buffoons than white-collar thieves.

The impact of the price-fixing case is therefore minimized, and it almost seems insignificant compared to the time spent discussing the money that Whitacre embezzled from the company. By the time Whitacre himself asks, “Why did I get more [prison] time for stealing $9 million than the people who stole hundreds of millions from American consumers?” it’s too late for the audience to care.

The Informant! has some amusing scenes (including cameos by several fairly-well-known comedians, foremost being a memorable turn from Paul F. Tompkins), but it comes off as pretty lightweight. The most likable characters are probably the FBI agents, doing their job as honestly as they can while surrounded by deception.

THE VERDICT

In summary, the book is a meat-and-potatoes look at a complicated case, and the movie spends too much time goofing off without ever being that funny. I’m not sure either gets to the heart of darkness at the center of American agribusiness, but maybe we don’t want to know about that anyway. I might have ruined our appetite.