In the classic era of the author, career paths for young writers did not stray far from a list of five or six possibilities. Their formative years were usually spent teaching, writing for a newspaper, witnessing the carnage of war as a soldier, sailing the high seas, performing odd jobs for food money or attending college as an independently wealthy upper-class twit.

In the classic era of the author, career paths for young writers did not stray far from a list of five or six possibilities. Their formative years were usually spent teaching, writing for a newspaper, witnessing the carnage of war as a soldier, sailing the high seas, performing odd jobs for food money or attending college as an independently wealthy upper-class twit.

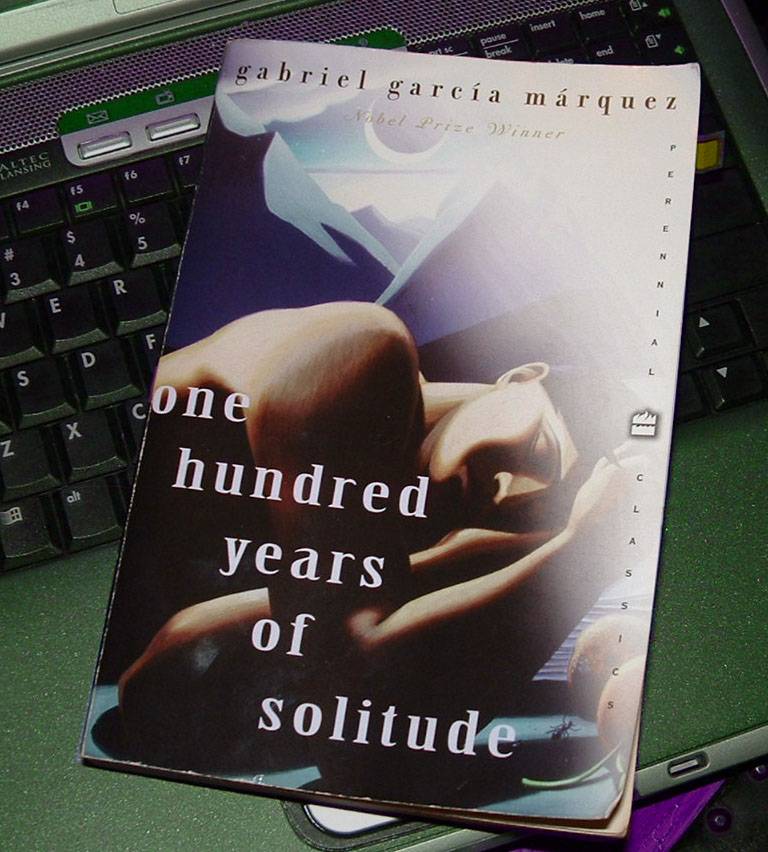

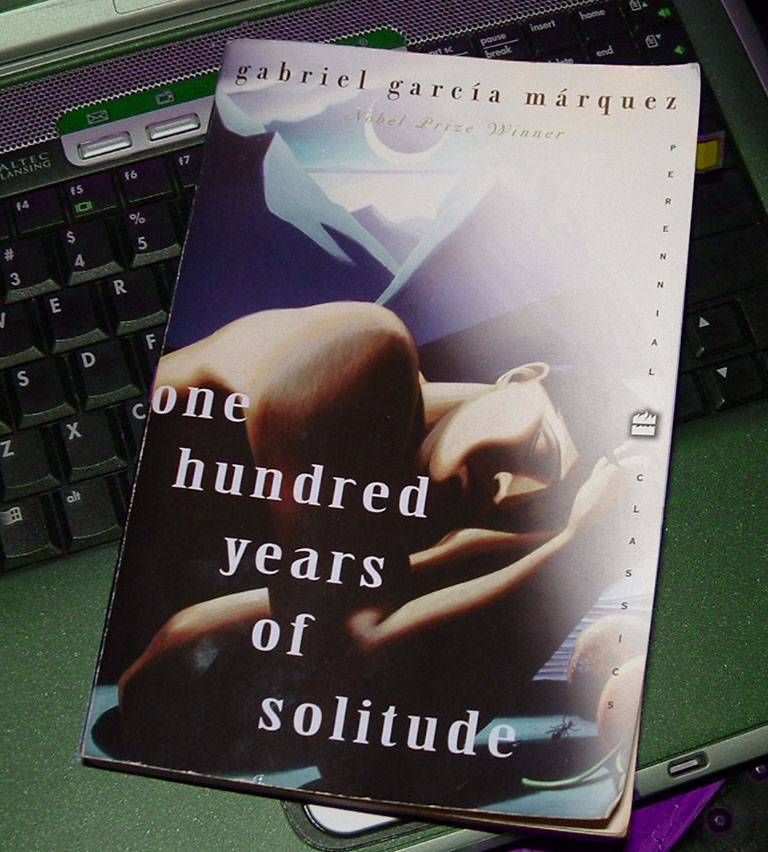

Before Gabriel García Márquez became an acclaimed author with a Nobel Prize, he was a perfectly respectable journalist. He wrote for several newspapers until his short stories began to draw attention. Then he locked himself in a room for eighteen months and wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude while his long-suffering wife pawned nearly everything of value to keep food on the table. The novel has since gone on to sell millions of copies throughout the world, to the great relief of Márquez’ wife.

When the author was a boy, his grandmother told him wild stories, mixing the mundane with fantastic exaggerations in the same tone of voice until they were inseparable. Many of the novelists swept up in the Latin American Boom of the 1960s must have drawn inspiration from their grandmothers’ stories, as their influence spawned a literary sub-movement called “lo real maravilloso,” Magical Realism. A prime example of this style, Solitude comes in close proximity to the surreal sphere of Alice in Wonderland. There are no talking animal characters or trippy existentialism, but there are gypsies, if that does anything for you.

Solitude follows the lives of the Buendía family line. The patriarch, José Arcadio Buendía, founds the village of Macondo where much of the story takes place. After fifty pages, it is easy to believe that anything might happen in Macondo: a plague of insomnia, an inexplicable ascendance to heaven or a rainstorm lasting four years, eleven months and two days.

Located near the front of the book is a diagram of the Buendía family tree. Refer to it early and often. José Arcadio Buendía and his wife, Úrsula, have three children: Aureliano, José Arcadio and Amaranta. And so on, and so on, as succeeding generations assume the same names. There are so many combinations of Aureliano and José Arcadio that it’s hard to keep everyone straight in your head, especially when they all have similar personalities.

The Aurelianos are quiet and prefer their own company, while the José Arcadios are all brash men, eager for the novelty of meeting new people. The boys also inherit indelible memories from their namesakes. So, while events and circumstances of their lives change, it seems the same two people are born again and again.

“The history of the family was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity were it not for the progressive and irremediable wearing of the axle.”

The consanguinity of the Buendía family probably contributes to the grinding axle. The original José Arcadio and Úrsula were cousins, products of centuries of intermarriage. Their families opposed the wedding, fearing the couple’s children would be born with tails, but the cousins marry anyway. Two of their sons have children by the same woman. An aunt sleeps with her nephew. As the family bloodline disintegrates, so does Macondo. Near the end, the village is empty. The dry wind sweeps both into memory.

Márquez’s novel did not blow me away. It is an interesting read, but the twists and turns of the plot were far more interesting than the characters. It didn’t change my life, but for Márquez, it was well worth the eighteen months of his own solitude. The widespread popularity of his first novel brought the royalty checks flooding in, which allowed him to quit his day job — a writer’s ultimate goal.

Rating: 3 of 5