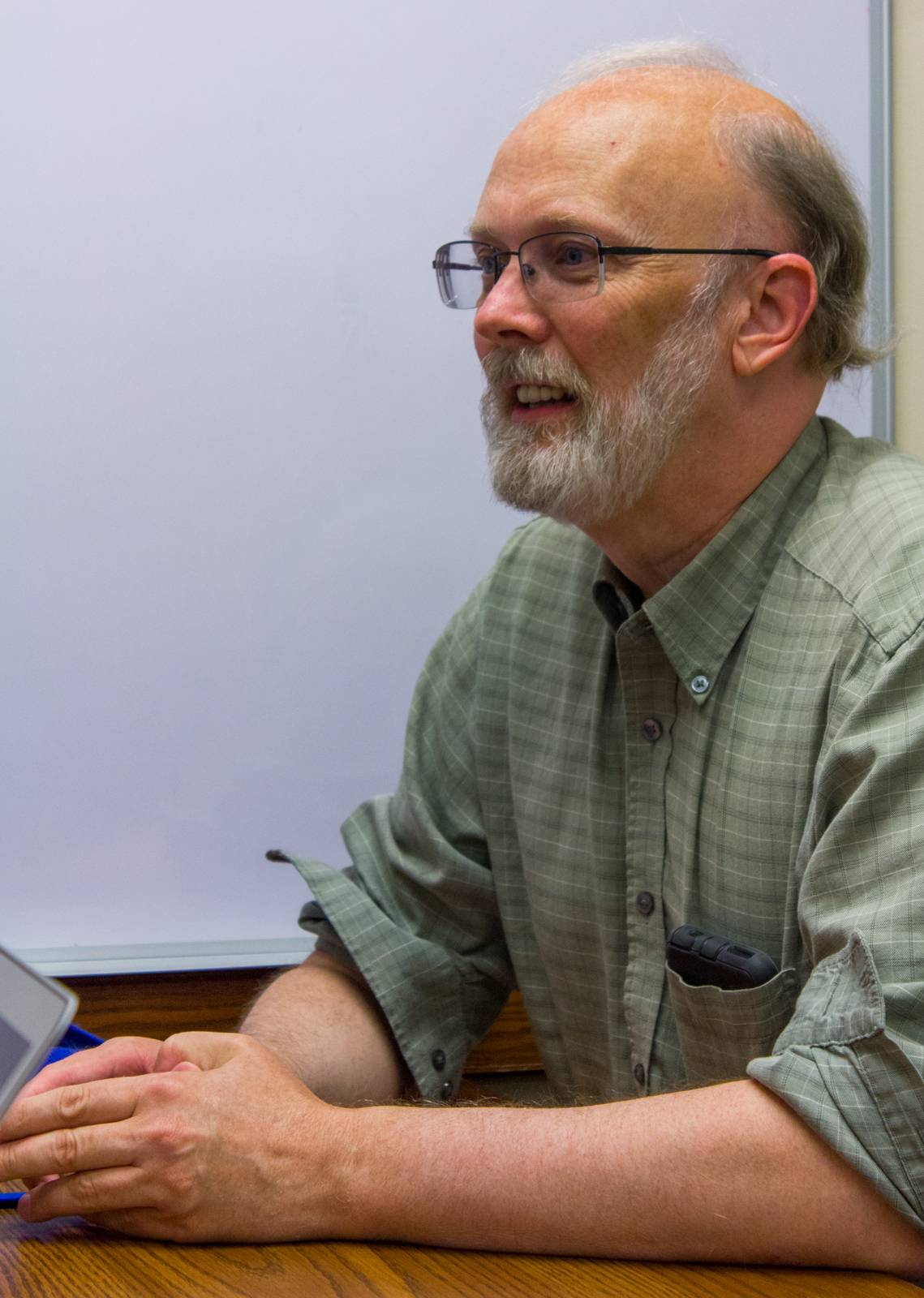

When Dr. Alan B. Craig was a child, he wanted to be a rock star. Unfortunately, he was born too late; younger than his brother and the other kids, Craig was not allowed to join their band. (Craig’s brother was older by six years and so we can’t really blame him for not wanting the kid brother in the band.) Craig’s only path to fame, it seemed, lay in his brother’s old tape deck. Like the band, the tape deck was off-limits. But life, as somebody somewhere says, finds a way.

Craig used the tape deck in conjunction with a neighbor’s tape deck to combine his previously recorded guitar tracks with additional parts, bouncing the tracks from deck to deck, making a kind of one-man-band. But the band existed only on tape.

Craig used the tape deck in conjunction with a neighbor’s tape deck to combine his previously recorded guitar tracks with additional parts, bouncing the tracks from deck to deck, making a kind of one-man-band. But the band existed only on tape.

This was his first experiment with virtual reality (VR).

In melding present and past, concrete here with the ghostly traces of somewhere and somewhen else, Craig was beginning a lifelong interest with VR and augmented reality (AR) that would lead him to a three-decades-long career at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA).

“How do these things exist when they don’t exist?” Craig asks aloud with a laugh and a shake of his head.

It is a question answerable only by confidence men and gods. And by scientist-philosophers like Craig.

We have more than five senses

Craig’s career traces the rise and fall and reemergence of VR and AR in our popular imagination. In the 1990s, when Caterpillar wanted to increase operators’ visibility in tractors, Craig helped the company embed operators’ motion in visualization, reducing the need for Caterpillar to build physical models. When Alma was being restored, Craig, fellow scientist Dr. Robert McGrath (who is also a writer for this very magazine), and company made sure she wasn’t missing from any graduation photos. He finds VR/AR in unlikely places, like the Norwegian pop band A-Ha’s 1984 music video for “Take on Me,” in which people move freely between a flat, imaginary comic-book world and our real, three-dimensional physical space.

But in the early 1990s, something happened.

“The web came on the scene,” Craig notes, “and much of the energy that had gone to VR/AR went into web development.” The web’s dominance prevails, even in our mobile age where we’re supposedly not physically constrained by our Internet devices.

Craig shows me a slide with a picture of a little girl holding a smart phone. She strikes a familiar pose. Her head is ducked, her hands are in front of her, clutching the phone, her thumb slightly extended.

Helenka. Photo courtesy of morguefile.com.

“The web stole away the world and the body,” Craig comments on the picture.

“Mobile broke the ties to the stationary computer, as we have it with us in our pockets wherever we go. But our lives are now in a 2×2 inch screen and our mode of interaction is this,” he says as he holds up one hand and mimes swiping and pushing buttons on his palm.

“We have more than five senses and I’m hoping that’s what we can capture back.”

The first thing that Craig wants us to understand is that there is a difference between virtual and augmented reality. Both are interested in altering human perceptions of reality using various technologies like cameras, projectors, and software. But there is a difference, one that is both philosophically profound and potentially politically charged.

The first thing that Craig wants us to understand is that there is a difference between virtual and augmented reality. Both are interested in altering human perceptions of reality using various technologies like cameras, projectors, and software. But there is a difference, one that is both philosophically profound and potentially politically charged.

VR is when a person experiences full immersion in an exclusively digital world. “Virtual reality offers the opportunity to engage bodily in the virtual world,” Craig explains.

But how this opportunity is granted and what constitutes full immersion can be tricky. For starters, virtual reality at the University of Illinois means for many the Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE).

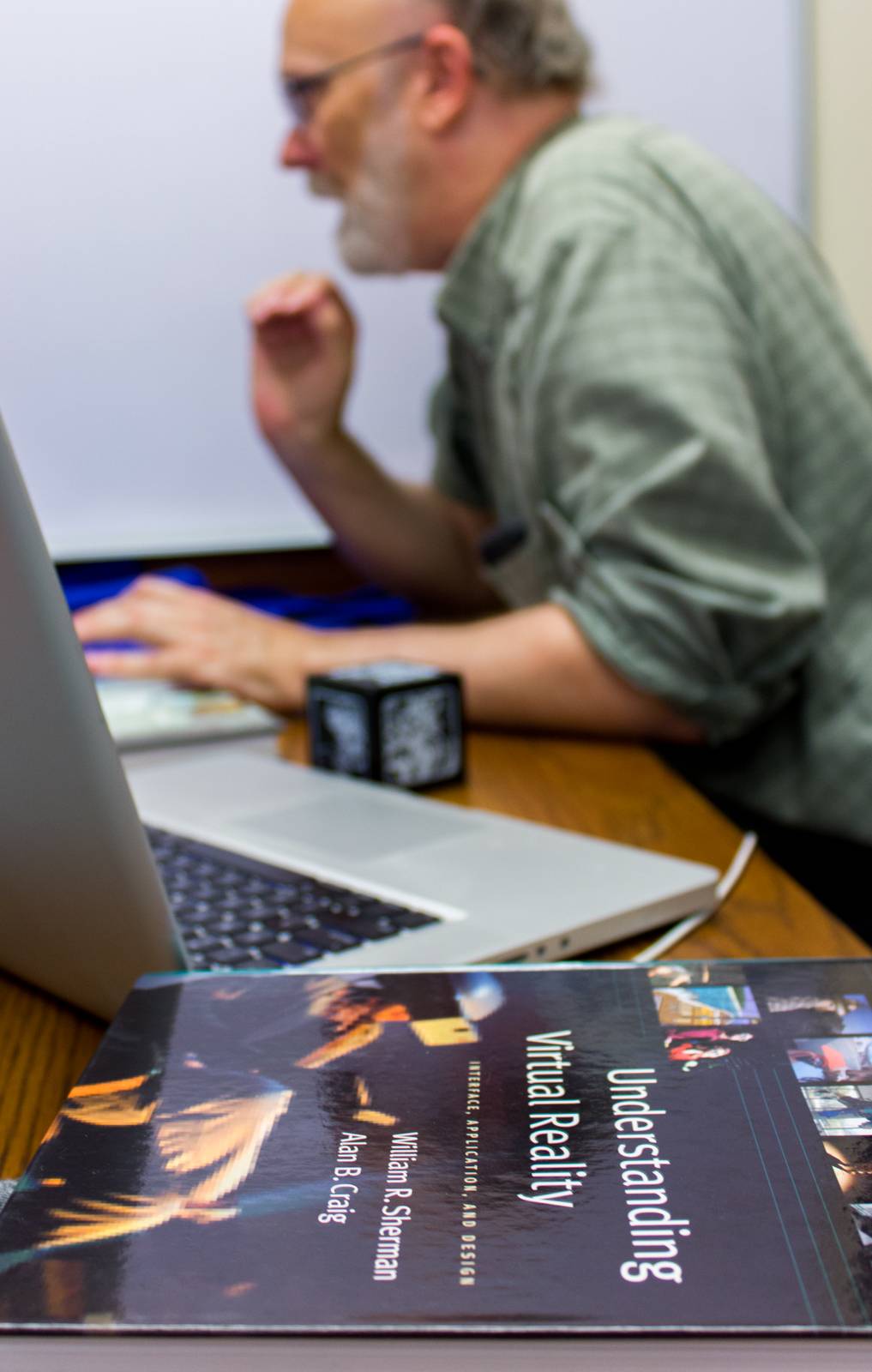

The CAVE is a room-within-a-room where participants experience, from Beckman’s website: “the world’s first room-sized immersive environment.” The CAVE is a multi-million-dollar project and access to it is restricted. And, yes, its name is both an acronym and a reference to Plato’s famous allegory, where men chained all of their lives within the cave’s walls mistake mere shadows for the real things that cast them.

Plato’s allegory of the cave. Image courtesy of genealogyreligion.net.

To others, it means that participants don a head-mounted display (HMD) such as an Oculus Rift and experience the digital world through the screens mounted in a device that looks a lot like a scuba mask. The mask includes sensors that tell the computer where the person is looking and what they are doing.

But even after gaining access to a virtual environment, VR still exacts a toll. And it can be quite high both individually and, especially, socially.

“To me, purely digital worlds shun our real world and our bodies. When you dive into a VR, you’re excluding the rest of the physical world,” Craig explains.

Even your own body tends to be left behind. People who practice virtual reality, for instance, are often so removed from their bodies in the process that they do not care about the appearances of the devices they are wearing. “You don’t see your own body,” Craig notes. Even though you cannot help but feel the “clunky weight of HMDs, especially when turning your head, you’re very disconnected.”

In the time it takes to draw breath, I think of Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One, of the freedom the protagonist feels when he straps on his OASIS headset and escapes the rusted trailer and dirty, slow flesh that marks his life in a dystopian 2044. I think of deep space and the promise of weightlessness.

I do not think of other people. Perhaps this is the problem with VR in its current state. To move into the digital is to move away from what most fully tethers us to this realm. People. Family. Friends. Random strangers we see walking along the street who, for just a second, capture our attention and we wonder where they are going and where they have been. “Unless I bring you in, you’re not there,” Craig adds. Silence fills the small room in which we sit.

Where virtual reality wants to strip the world away in order to give us a new one, augmented reality wants to give us two worlds in one. This orientation is evident, for instance, in the following live augmented reality video from National Geographic.

For Craig, augmented reality “embraces the fact that we’re in a physical world, in a physical space, and that we want to bring the best of the digital into the world with us.” I ask what the “best” means, ever fearful that the advertising hellscape of Back to the Future II is just on the horizon.

Virtual shark attack outside of the Holomax, Back to the Future II. Image courtesy of news.com.au.

Craig commends my narrowed-eyed skepticism, and mentions that he has given a brief lecture on just this issue for a marketing class accessible on Coursera. (Spoiler alert: no hellscape is coming.) And he offers the hope that we each get to decide what is best for ourselves.

I’m making that curation for myself. I want the best of this thing, of what I care about, of what’s meaningful. We can have the best of the physical world and the best of the digital world at the same time. We’re subject to what developers provide for us now, but in the future, more people will be able to be creators rather than just the software developers. You won’t have to be a technical person to use augmented reality, to make a world with it.

Making a world is, of course, building a story in brick and stone, or in this case, in bits and bytes.

This work is about dreams

The second thing that he wants us to understand is that VR and AR are not technologies. They are media. To explain the difference, Craig turns again to popular culture, this time film.

If I asked you what a movie was, let’s say I had no idea, and I asked you what it was, and you said, ‘Movies are made with cameras and certain kinds of lights, and are shown with a projector,’ is that a movie? Not at all. Those are the technologies that make the movie possible. Movies are not projectors and lights. Movies are a medium through which we communicate and we tell stories.

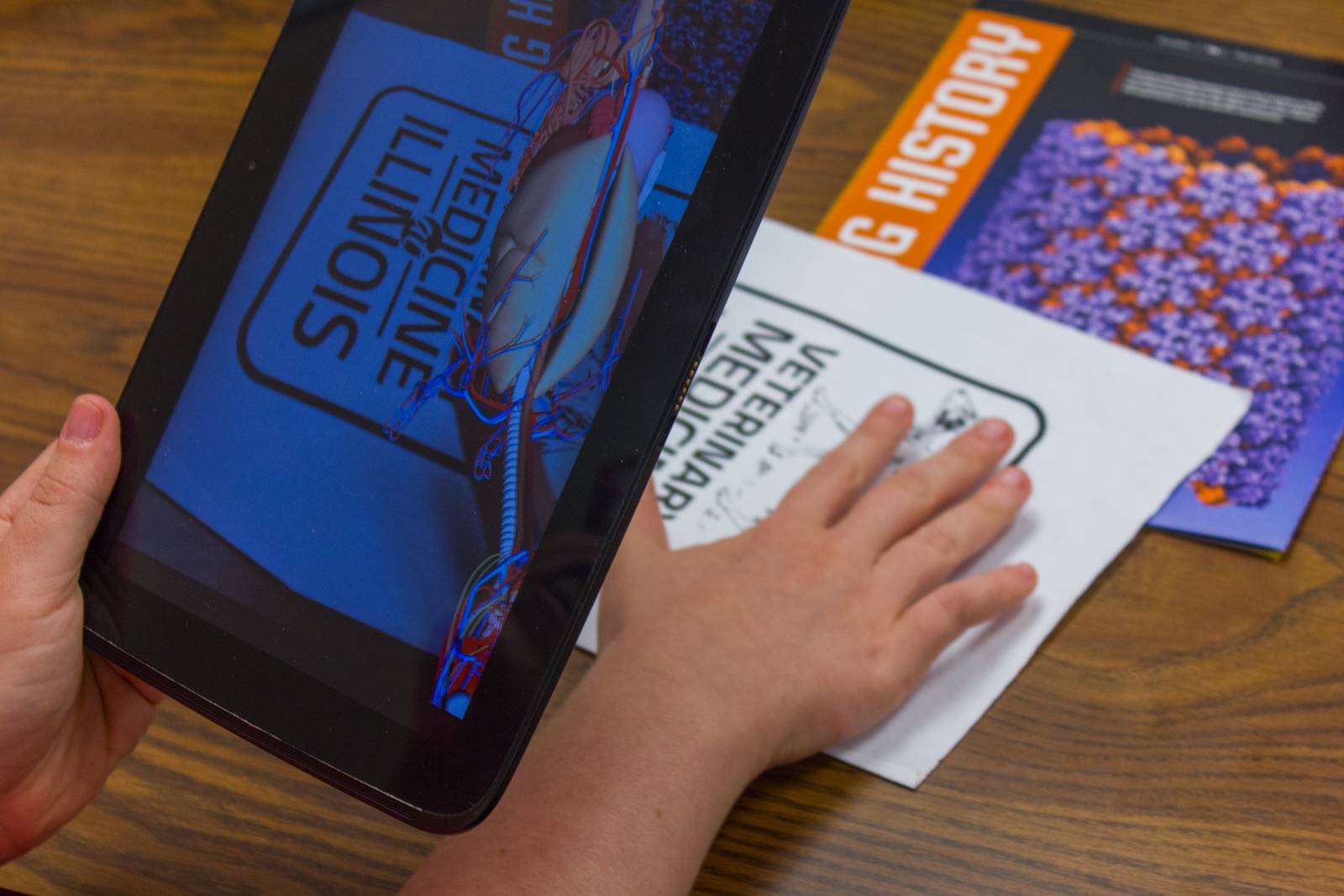

He demonstrates what some of these stories, told through AR, look like. Out of a blue recycled plastic shopping bag he pulls some of the most ordinary equipment I could expect. There is an iPad, an Android tablet, an NCSA magazine, a t-shirt with a heart on it, a block, and a piece of paper with an outline of a cow’s body printed on it.

He flips open the magazine to a page with a photo of a man on it. He loads the DAQRI app on the iPad and holds it over the image of the man. Suddenly there is sound; the man is speaking and moving in the app. I involuntarily gasp and fight the urge to check under the iPad for a tiny animate person somehow freed from the page. Craig laughs, his eyes sparkling. After three decades in this work, he looks at me with a huge smile and says, “Just like in Harry Potter, right?”

When he waves the iPad over the t-shirt, an orange and blue heart starts beating. When it hovers over the block, it becomes a rotatable object that, with just the touch of a button springs open to reveal its inner workings.

But the paper was true magic. It was a project Craig did with Vet Med. When its time came, an interactive three-dimensional cow body appeared to stand on the table. When Craig touched the paper cow’s head, the virtual cow’s head revealed a brain. When he touched the paper cow’s chest, the virtual cow revealed sharp white ribs.

Cow skeleton. Image courtesy of Alan Craig.

Cow skeleton. Image courtesy of Alan Craig.

But AR does not end with the iPad. Even as Craig marvels at the technology he helped create, he also seems a bit embarrassed by it, as if the technology was an A student who came home one day with an inexplicable B+. He remarks often on the iPad’s undeniable presence. “It’s in your way,” he says as I joyfully twirl the iPad above the paper cow. “It constantly reminds you that there is technology involved. But what if AR worked through your glasses?” he asks, tapping his own eyes. “What if it didn’t even need those?”

“That would be cool,” I say, eloquent as always and not really understanding why he seemed disappointed. “But I don’t really feel the iPad sometimes.” And it’s true, I didn’t, especially when I first saw those animated forms emerge on the screen as part of our world.

Craig is right, though. The postures I was holding to sustain that AR experience are not, in the long run, physically sustainable. Muscles just will not stand up.

He smiles again as if he has forgiven the iPad its sins. “But you were using your whole body to see those images, standing, moving the iPad this way and that. You weren’t just sitting there staring into a screen.”

The true story here is not the way in which the app is programmed to read objects in space (though that is really cool). And it’s not even in the cooler technology that’s hovering just on the cusp of reality. Thinking like that, Craig reminds us, is still too small.

Craig noted that the time was coming when I will be able to project a clock on my right hand and see without a bulky gadget mediating the experience.

“But how would I interact with it?” I ask, pushing my index finger and thumb apart in the familiar enlarge gesture on the ghost clock on my hand.

“There’s many ways we could interact with it, but that’s not the only important question to ask,” Craig responds.

The question is, what do you want to see? What do you want to happen? We should never limit what we want by the technology we have today. If we want something that is feasible today, that’s an engineering problem. Engineers evaluate what we have and build solutions today for our problems. If we don’t have the technology currently we will invent it.

He pauses a moment.

“But this work is about dreams.”

For more information on augmented reality, see Dr. Craig’s book, Understanding Augmented Reality. (Picture to right, courtesy of amazon.com.)

For more information on augmented reality, see Dr. Craig’s book, Understanding Augmented Reality. (Picture to right, courtesy of amazon.com.)

Unless stated otherwise, all photos taken by Stephen N. Kemp.