Perched on a deck chair atop the manicured lawn of Maui’s Sheraton, Jerry Hester appears at ease, no fidgeting. It was the same in his playing days. Unflappable, stolid, serious.

These are apt adjectives to describe the 6’6” star forward of Illinois’ 1998 Big Ten basketball champions. Whatever’s going on inside, you can’t read it from his countenance.

Sea breezes waft over the Black Rock Cliff, a hundred yards west of the lawn. The Jacuzzi grotto gurgles softly, a few paces to the south. It’s about 80 degrees, but not too humid. The sun is shining.

You’d hardly know that Jerry is having the worst time of his life. He’s just starting to appreciate that, in a way, it’s also the best time.

“I’m not very technologically savvy,” said Jerry. He’d never had a Twitter account. He’d never used Skype.

That was last week.

Now he’s signed up with both communications networks. These two little changes in his life were prompted by one huge change in his life: His dad died.

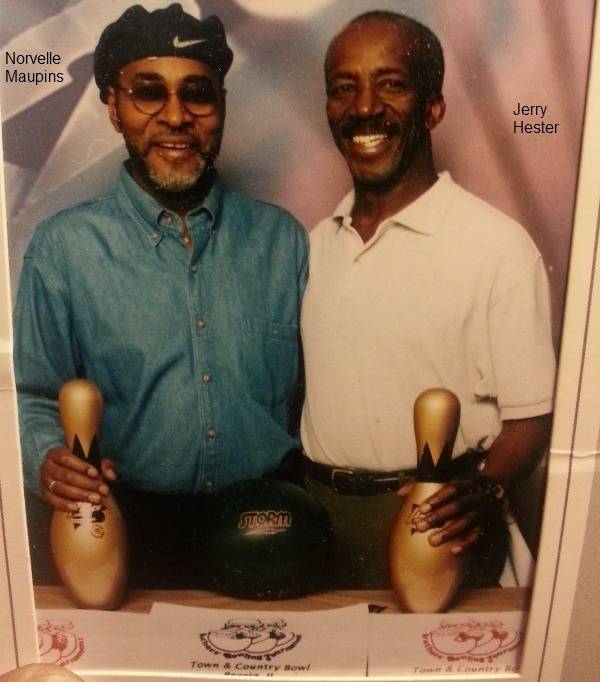

Friday evening, November 16, Jerry Hester Sr. lay unconscious in a Peoria Methodist Hospital bed, mortally felled by an aortic dissection. It was completely unexpected. He’d seemed perfectly healthy. Two weeks earlier, he just missed bowling 300, leaving the #9 pin on his penultimate turn.

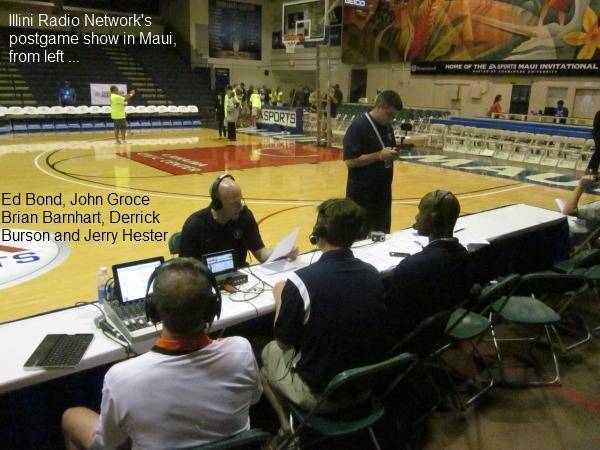

Jerry Hester II was in Honolulu, trying to get his wits together in time for the live broadcast of the Illinois-Hawaii match-up. He’s expected to provide cool, collected observations about a game. It’s not so easy when real life socks you in the gut. But Jerry decided to plow through. He called the game in Honolulu, and then flew on to Maui for the EA Sports Maui Invitational. Illinois won the tournament, handily.

“My dad and I had what I thought was a really good relationship. But it turns out we had a great relationship. He taught me to be a man.

“The reason I stayed (in Hawaii) is that he listened to every game on the radio. We talked after every game. And he would want me to be here. He wouldn’t want me to sit at home and be sad. He would want me to be here and continue to do my work. That’s what he would say all the time. ‘Do your work.’”

Hester Sr. was a glutton for work. Born July 2, 1944, he grew up in East Saint Louis. “They wore orange & black, like I did at Manual. He wore #40, so I wore #40.”

Hester Sr. studied Social Work at Arkansas–Pine Bluff, and took jobs in corrections counseling at Hanna City and Wilmington, where he met Bonnie Slaughter. They married in 1968. Hester Sr. then took a job at Caterpillar “like a lot of people in Peoria did,” recalls Jerry II.

If the typical factory employee comes home, pops a beer, and plops on the couch, then Jerry Sr. was not typical.

When he came home from work, he’d work some more. Just for the enjoyment of it.

“My old grade school, Christ Lutheran, had this huge tournament. Sixteen teams in this tournament, so they wanted to put up banners for each school.” But after designing a few, tournament organizers ran out of ideas.

“This was years ago, back in the eighties. So he created these banners, and painted each one by hand, at home, when he got off work. Working eight hours, doing that for nine or ten hours, and sleeping for three or four hours, and then going back and doing it every day until he got done.” That’s just the type of person he was.

Jerry leans forward from his deck chair, and draws a triangle in the air, about four feet high. His hands move, perhaps, the way his father’s hands moved across the medium, etching here, adding a brush effect there. Each creation unique and particular to the kids and community represented.

Maybe the original plan was to employ the banners just for that year. But the plan changed. “They stayed up for …” Jerry pauses to tabulate the years, before realizing “they may still be there. I haven’t been back to town in a while.”

Things changed at Caterpillar, but Jerry’s dad wasn’t finished working. He finished his degree in Social Work at Bradley. “For the last fifteen to twenty years before he retired, he worked with alcoholics and drug addicts, helping them get off the street in Peoria. He really enjoyed helping other people.”

“Helping other people” is the concept that keeps recurring as Jerry recounts the life and death of his father. It’s a theme within the Hester family. In their absence, and 5,000 miles from home, Jerry discovered it’s common to the Illinois basketball family as well.

“In times like this, most people would want to be with their families. But the one thing that I realized going through this is that even though I’m not with my mom and my sisters, I’ve had the Illinois family to really support me.”

Phrases like “the Illinois family” can sound corny when trotted out for a press release. But the people closest to the game share a common understanding. They’re real humans — despite the celebrity and its media trappings — warts, fetid foot odors, and all.

“Right after the game, when coach (John) Groce talked about it in the post-game and Steve Kelly mentioned it (during the radio broadcast), it’s just been non-stop support from people — a lot of different people. You probably couldn’t even put that many names in the newspaper — in an article — and still write the article.”

People who’ve experienced emotional trauma know about the incessant rush of thoughts and memories that pummel one’s mind in the aftermath of personal tragedy. You can’t shut them out. They just keep coming. Lying fitfully in bed, looking at a mural, the smell of pancakes and coffee. Just about everything jars a memory.

When facing hard times in the past, Jerry usually turned to his dad.

“If you had an issue and you brought it to him — I don’t know if he did it on purpose, because of his background — but he always made you come up with the answers. He would never judge, or give you the answers. He would just listen. And a lot of times, with some difficult things I’ve had to go through personally, talking to him was extremely helpful because I ended up coming up with the answers just by having him listen to me.”

So who do you turn to when the one who’s always listened is the one you can’t turn to, never, ever again? Jerry Hester II discovered that the answer is “a lot of people” — more than he ever knew, and some that he hardly knows.

“I just got a call today from somebody that I just met last year at the Final Four. She’s a U of I grad and her husband is not a U of I grad, but they opened up their home to us when we went to the Final Four. We haven’t spent a lot of time with them, but he gave me a call this morning that was very touching. Just talked about the fact that he had been through it twice with both his parents.

“In his way, which had some cuss words in it,” and here Jerry chuckles at the memory, “he made a difference.”

Hester pauses to recollect another piece of wisdom from a man he’d met the previous morning, while exercising in Maui. “He just lost his dad. This was a trip they were supposed to take together, coming out here together. Couldn’t do it.

“People that have been through it, and some of the stories they’ve been able to share, some of the feelings they’ve had — that I’m going through now — it’s been helpful.”

In the Hester family, being helpful is a core tenet. It’s a professional calling and a pastime.

“Most people don’t know this, and I probably never talked about it publicly, but after my basketball career I thought about being a fireman. Because my mom and my dad both work in jobs where they help people. And that’s something I always wanted to do just because that’s what I saw growing up.

“I went another direction in helping people — obviously [he chuckles again] — with my financial services industry career.”

Bonnie Hester worked at the health department in Peoria. “She did that for, oh I don’t know … thirty years? I don’t know how long it was, but she retired a couple years ago. And now she’s an elected official in Peoria, County Board.

“It’s funny because my dad’s not into politics at all,” Jerry continues, slipping into the present tense to describe the difference between his parents. “So they used to fight, in a loving way, about the fact that he couldn’t stand politics and she was involved in it when she retired.”

Apart from politics, the Hesters were a tight-knit family. Jerry has two older sisters, Lorry and Amie. He says they all had good relationships with their parents. When Jerry Sr. was stricken, they all came together. But because Jerry II was in Hawaii, and Lorry lives in the nation’s capital, they came together via the Internet.

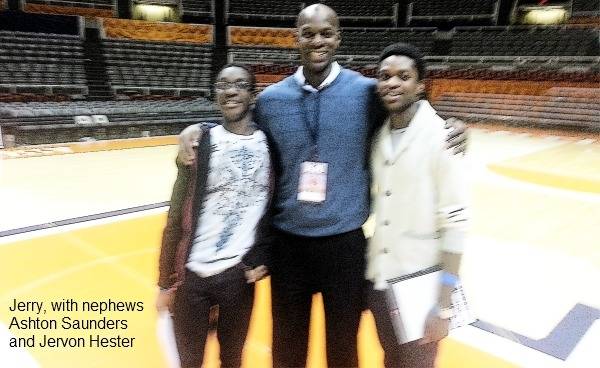

When the family convened at Peoria Methodist, family friend Jan Martin fetched a laptop. Amie’s son Jervon, 17, helped the older Hesters install Skype. Jerry signed up too, from his hotel room in Honolulu. Lorry signed on from Washington.

In Peoria, the surviving Hesters pointed the laptop’s webcam at Jerry Sr. so his son and daughter could see him one last time, and say goodbye.

And then an idea struck Jerry II. He realized he could use modern technology to keep his dad’s memory alive, both within himself, and for others. He signed up for a Twitter account, @JHes_Legacy.

“The reason I named it ‘Legacy’ is because, after my dad passed, ‘how can I honor that person, and keep him in my life?’

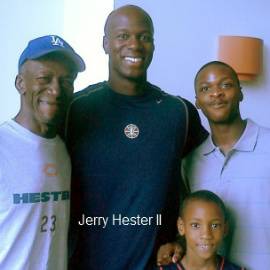

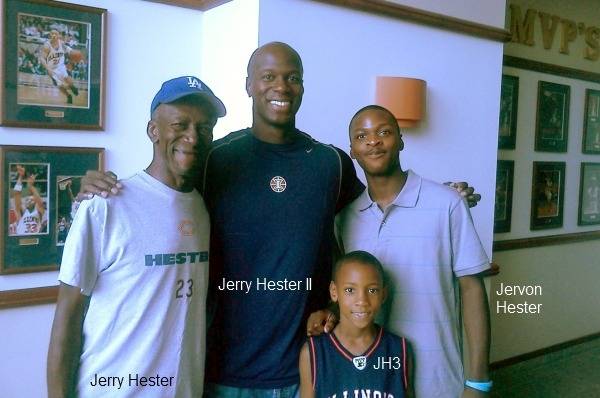

“What I realized when I looked in the mirror Saturday morning is that we have the same name, and that’s the legacy. And my son has the same name. He’s the third. And I named my Twitter account @JHes_Legacy because … you know I named my son Jerry because of the way I feel about my dad, not because of how I feel about me.

“Hopefully, if my son has a son he’ll do the same thing.”

Does he look like his dad? “Exactly.”

Does Jerry III (now eight years old) look like his dad? “Exactly,” Jerry declares, before adding “well, he’s a little lighter.”

Through Twitter, Jerry hopes to reach out to everyone who was there for him. And to share the wisdom, the legacy of his father, whenever memories pop up.

And yes, there will be tweets about basketball too, especially adventures with play-by-play partner Brian Barnhart. “Oftentimes, Brian and I go to these crazy, hole-in-the-wall places,” he says, adding that his favorite television show is Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives, a theme with which he’s had extensive experience in the seven years since he joined the Illini Radio Network. “I’ll tweet about all the fascinating people we meet on the road.”

Finding comfort in life’s oddities and absurdities is, perhaps, an inescapable component of confronting profound loss. It’s helped Jerry cope. But it’s also helped him remember. He cherishes each memory that pops up. And then shares it.

“Obviously there’s emotions, up and down. But for the most part …” He pauses again. “I’m doing as well as I can, I guess you could say.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Previous versions of this story appeared in the Peoria Journal-Star (Tuesday, 12-4-12) and Champaign News-Gazette (Thursday, 11-29-12). I encourage you to buy a hard copy. It turns out we here at Smile Politely favor the printed word. My thanks, and warm feelings to the Hester Family.