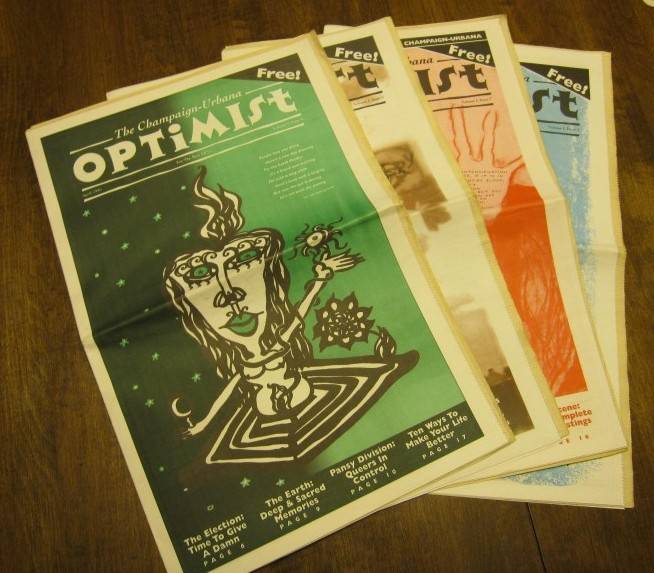

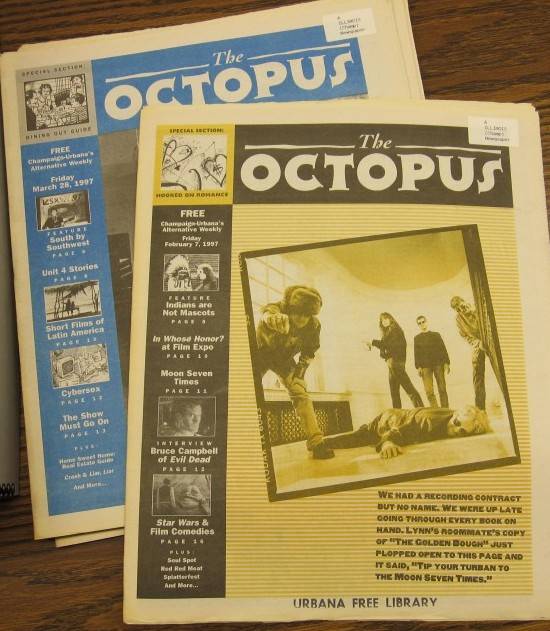

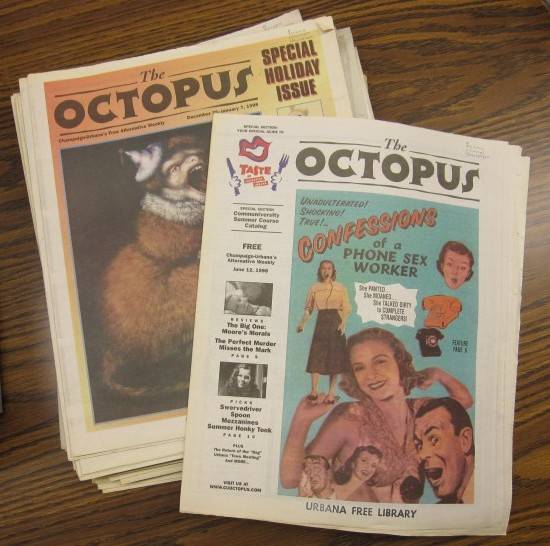

Eight years. Three names. Three owners. In its tumultuous tenure, the Optimist/Octopus/CU Cityview made a tremendous impact on the Champaign-Urbana community, an impact which still survives to this day. Every would-be journalist who attempts to shine a light where there now is darkness, every every citizen who writes something “for the rest of us” to read is following in the footsteps of the folks who soldiered on despite long odds.

It’s a play in four acts, with each change in ownership (progressing from idealistic to oblivious to cynical) bringing the paper closer to its ultimate fate, but the staff kept cranking out quality content every week regardless of who was watching the balance sheet, and whether their paycheck bounced or not.

The Octopus is kryptonite to Google’s Superman. Search engines cannot penetrate its paper-bound history, and that’s a shame which will hopefully be somewhat rectified with this article. The people who created this legacy still have memories of how they made it happen, and their experiences are incredibly relevant eight years on.

Thanks so much to everyone who gave so freely of their time for this history project: Paul Young, Jenny Southlynn, Doug Hoepker, Shelley Masar, Holly Rushakoff, Jeff Ignatius, Greg Springer, Mike Knezovich, Marci Dodds, Paul Kotheimer, Jason Pankoke, Ed Burch and Carl Estabrook.

PART I: A PORTRAIT OF THE OPTIMIST

Paul Young (Founder, Publisher: 1995 to 1997): Here’s what inspired me to start an alternative paper in Champaign. Way, way back in school, this would have been from ’79 to ’83 or so, I worked at a paper called The Weekly. Michael Metz was the owner/editor and there were offices near the Orpheum Theater, upstairs, maybe above the drapery place or something like that. And I was — I’m a graphic design major at U of I — so I did layout and production for them, paste and setup. So, that was my first taste of the newspaper business. I just learned by observing, understanding how it worked — it was a free paper of course, advertising-supported, so… He wasn’t the first, of course; there were many, many attempts at weeklies or alternative publications, and I admired their spirit, the way they work, and it seemed like a fun place to work. So, that sort of was in my memory. And the second part of it was traveling: I had a job in New York where I would travel a lot; I was a photographer’s advisor/counsel — these are commercial photographers, not fine art photographers — and I would be sent to Seattle, San Francisco, New Orleans, Miami, Minneapolis, wherever there are viable arts and cultural centers where commercial photographers do well. And wherever I went, this would be my late 20s, early 30s, to me, traveling was great fun. Whenever I would visit a city I’d never been to before, Minneapolis, for example, you have appointments, and the rest of the time, you have to find something to do. So, where do you look to find music, theater, dance, art, culture, where are the cool restaurants to eat, and so on? Every one of those cities had an alt-weekly. It was the source; the daily had nothing. So, if you wanted to know what to do in a city where you’d just arrived in, and the internet didn’t exist, consulting the daily made absolutely no sense. So, the fact that there was a network already, across the entire United States — every city that was cool, worth visiting had an alternative weekly, and Champaign-Urbana didn’t. So, when I came back…So, I just thought Champaign-Urbana was cool enough to have an alternative weekly like Madison or Ann Arbor.

Jenny Southlynn (Jack of all trades, 1995 to 2003): [Paul’s] wife, Bonnie, had a space in downtown Champaign, and she was doing some bodywork and some holistic healing; it was called the Whole Life Center. I’m a painting teacher, and I was going to do a painting workshop, and they gave me permission to do it at the Whole Life Center. So, that’s how I met Paul. We just hit it off, and I think he realized that we had a similar vision. He showed me his brand-new publication, and I was so excited, just to see the paper that he had created, the visual component of the paper alone were just unlike anything else in town. As a graphic designer, he’s first-rate. He had created prototypes for ads for the businesses in town, and I think that’s how he sold it: he took it around and showed all the businesses: “This is what I can do for you.” Just the fact that it was going to be a grassroots thing; he was going to draw from the community: creative, intelligent, energetic to participate. He had a meeting or two at that Whole Life Center space, and groups of people that were interested in graphic work, photography… a whole array of people just showed up, and everyone was willing to contribute in some way. And eventually, it just started to jell.

Paul Young: So, I had a computer, I had the skills as a graphic designer, it was the first issue, basically, I paid for out of my own pocket. We gave away free ads, that was the initial business plan: if we could show them… It was wrong to ask for money for something that doesn’t exist — how do you sell something that no one has ever seen? So, the idea was if we created a good enough first issue, gave out free ads, two things would happen: the people that we gave free ads to might like it enough to pay to be in the second issue, and once it was out, their competitors — let’s say if Strawberry Fields had an ad, which they did the first issue which we gave them, and I’m not sure who their competition was then, there probably wasn’t one, but let’s say Strawberry Fields had a competitor — “Oh, my gosh, Strawberry Fields is advertising in this publication, maybe we should too!” And it worked. It worked well enough that we were able to pay writers $20 for a story — and we’re talking 750 words, so it wasn’t much. It wasn’t much money, so it wasn’t a professional writing fee or something like that, but it was enough that people wanted to write for us. In terms of content, there was never enough space. So, then of course, the amount of space we had was completely dependent on the amount of advertisers we got. So, that was basically how we started.

Jenny Southlynn: None of us were journalists. They had a couple of people that stepped in as editors, like P. Gregory Springer, that had a background in journalism, a couple guys in there; no one ever lasted very long.

Paul Young: My favorite writer was Shelley Masar. She was not a writer, she was not trained as a writer, and she struggled [with] writing. Often her writing needed some heavy editing to clean up, etc., but she was fearless in terms of the subject matter that she tackled.

Shelley (Masar) Washburn (Freelancer, 1995 to 2000):

I recognized Paul’s intentions to do this thing as well as it can be done anywhere and do it here. I loved that, and he was willing to take risks and hire people – the usual kind of hiring in Champaign-Urbana: I will hire you without paying you, but I will do everything I can to let you do what you want to do the way you want to do it, and if there’s any money at all, I’ll give you what I can.

Paul Young: It was a monthly, not a weekly. The name was the Optimist, not the Octopus, and the logical reason for the name is my life philosophy, or at least my friends tell me my personality is such that I’m an eternal optimist, so that seemed like a natural. We had to change our name — we were forced into it, we didn’t want to change it — by the Optimist Club. They didn’t like the fact that we used the same name as they did. Even though they’re not very active in the community, they didn’t want us to use their name. I think we got a letter from their lawyer. We did interview them, in our first or second issue we even wrote about the Optimist Club, but they didn’t like us. They didn’t want to share their name.

P. Gregory Springer (Editor, 1995 to 1996): The reason Paul called it the Octopus, I think, was because it had sort of taken over his whole life, and he and his wife were joking about how it was like an Octopus. There was an earlier underground newspaper back in the days of underground newspapers called the Walrus, so he thought that tied into Octopus, too, kind of.

Paul Young: When it became a weekly, it became a full-time job. But, even so as a full-time job, I was not able to draw a salary, believe it or not. So, what paid for the paper, or what paid my bills, anyway, is still freelance graphic design. The staff got paid first. Well, obviously we paid the printer first. If you don’t pay the printer, the next issue doesn’t go out. The rent’s gotta be paid; we actually had offices, over the Dallas and Company. So, there was rent and electricity… The hierarchy was printer first, rent, then staff, and then there was no money left over, so I didn’t get paid. It was never profitable, but it was fun.

C.G. Estabrook (Political columnist, 1995 to 2002): Paul Young called me — I did not know Paul at the time — and said, we’re putting together a paper and we know you’ve been doing this radio program, “News from Neptune,” would you like to write about that for the paper. And I think my first question to him was something sophisticated like, “Are you going to pay?” When he said yes, I said yes, of course. If he’d said no, I’d still have done it.

Paul Kotheimer (Music editor, circa 1996): I learned a lot from all the folks I met there, especially Paul Young. The staff were very gracious to put up with me back when I was an insufferable prima donna twentysomething. I guess I’m pleasantly surprised by how many folks from the Octopus I still meet and greet around town after all these years. Many of them have stuck around.

Jenny Southlynn: We did stories on everything from dildos to… you just can’t even imagine.

Paul Young: In fact, I would like to take credit for starting the Buzz. Not so much that I had anything to do with it, but the reason that the Buzz exists is that the Octopus existed. The Buzz was created to compete against the Octopus. The Daily Illini started a weekly entertainment magazine that could have been called the Buzz from the beginning in direct competition with the purpose to compete with us for advertising. I have a funny story to tell about that. Of course, it’s a student-run paper, and they tried to struggle to keep up with us in terms of music listings, etc. We discovered in reading their music listings that they were basically copying us. So, they would grab our issues as soon as they came off the press, which was on Thursday, I believe, and they would quickly write up their stuff for their Friday issue. And we didn’t want to sue them or anything, but we wanted to catch them, so to speak. We were friends with many of our advertisers, and Cody [Sokolski], who is One Main, used to own Periscope Records, which was right downtown here. He had this stage in Periscope Records, and he would book bands every now and then. We called Cody and said, “Want to play a joke with us? Let’s make up a fake band and pretend this fake band’s going to be on your stage.” We made up a name, wrote up a super-cool, hip description of the band, non-existent in fact, just to see if the people at Buzz would pick it up, and they did. And of course, as soon as they picked it up, the next week, we embarrassed them by putting it in print. Of course, the [music] editor immediately got fired. I actually called their music editor, as soon as their issue came out. I picked up the phone and called the music editor and said, “So, tell me about this band that you just wrote about.” And he wouldn’t admit to me, he hemmed and hawed, but I think he realized [he was caught]. It was probably the scariest phone call — the blood probably drained from his face when he got the phone call. And unfortunately we got him fired, but that was a fun story.

PART II: THE END OF THE BEGINNING

Paul Young: It was fun, I’m glad I did it, but I wouldn’t do it again.

Jenny Southlynn: Because once it became the Octopus, Paul was on the brink of bankruptcy, and he was forced to sell the paper.

Paul Young: I ran out of money. I didn’t have enough cash because we were always in the red, we were never profitable, ever. The only way to keep it going was to get someone with deeper pockets, so that’s why we sold.

Jenny Southlynn: Initially, he actually offered it to two of us on the staff: Sandra Ahten and myself, because we were just there all the time, we were loyal, we were perfectly willing to just take it back to the basement, so to speak, and just try to do it on a shoestring. But, these guys from Yesse! [ed.: pronounced yes] Communications stepped up and bought it. They apparently were buying weeklies all over the Midwest.

Paul Young: Why [would they] want to do that? I don’t know, because in my opinion it’s not a very smart business decision. In terms of a way to put your money, I would say if you want your investment back with some profits, alternative weeklies is not the smartest place to go.

Jenny Southlynn: They picked it up right after we settled into the building where Mad Dog Press is, right above Dallas and Co. I found the space, and I was very excited about it because I’m a painter and I wanted to teach painting classes, and I also saw that it could be used by the newspaper as its production space, and we could split it. That’s exactly what we did: Paul and I signed a lease together, and I used half of it to teach painting classes and run to the other side and do whatever I needed to do for the Octopus.

Doug Hoepker (Ad sales, General Manager, Music Editor, Distribution Manager, 1999 to 2003): The entrance for it was off the dock at the back alley, so you’d step onto the dock and walk into the back of that space and go up the stairs. So it definitely was not a public face for the newspaper; it was tough to find us.

Jenny Southlynn: And not very long after these guys bought it, they turned around and fired its creator; they fired Paul. And it was shattering, it was really, really horrible, because he was the creative inspiration for the whole thing. I was there the day they let Paul go and announced it to the staff. We were all so… it was just the ultimate violation to let go of the creative heart of the paper. I just said to Paul — and I have no idea to this day how he feels about it — but I promised him that I’m going to keep that paper alive. A lot of people were going to quit in protest, and I just felt his vision was such an important aspect of this community, it became so vital a forum, that I didn’t want to see it die. It was his vision and I wanted to keep it going. I told him that, I whispered in his ear, I said, “I’m going to keep this going.” And I kind of flew under the radar, and somehow or another, I was kept on all the way through to the end.

Paul Young: I was actually fired because of one specific story. It was the La Bamba’s story. I interviewed two people who used to work with La Bamba’s and they got fired. And I tape-recorded the entire conversation about their treatment and Shelley and I both edited the article and printed it, and we made one factual error. In the interview, it came out that what I thought they said was that the owners had been in jail for some reason, I can’t remember the details. There were two brothers who owned La Bamba’s, but the factual error was that only one of the brothers went to jail, but not the other. So, legally, if you say someone’s been to jail and they haven’t, it’s stronger than [libel], it’s one level above it, I don’t remember the exact term, and you can be liable for that [libel]. And we were actually sued by them, and Yesse! Corporation actually had to pay out a fee for that, I can’t remember an exact amount, because at that point I didn’t own the paper any more, so any legal expense was the responsibility of the corporation.

Shelley (Masar) Washburn: Paul was a freer spirit than Jenny or the editor after him, and I missed his willingness to take risks, even though I knew the price of it.

PART III: WORKING FOR THE YESSE! MEN

Jeff Ignatius (Editor and eventually Editor and Publisher, 1998 to 2000): When I was there, the Octopus was a young publication run by green people (in terms of their experience in their current jobs), and it begged for hands-on management by experienced, on-site people. But from August 1998 to July 1999, there was no on-site publisher, and after that the on-site publisher was me — a relatively young journalist who was learning the business end on the job. That’s not a recipe for success.

Holly Rushakoff (Everything from Music Editor to Graphic Designer, 1999 to 2000, 2001 to 2003): When I was there, Jeff Ignatius had to create some code of conduct manuals [with rules], one of them being you can’t come to work drunk.

Jenny Southlynn: They moved us into different offices, you know, a little more upscale. They moved us into the building on Main Street, the Lincoln Building. They started us with a fresh set of editors — they had an editor, a young guy, that came down from the Springfield paper, and he had some experience: his name was Jeff Ignatius. He was a terrific editor to work for.

Holly Rushakoff: I thought one really cool device that Jeff Ignatius started [was] this giant corkboard, it was almost the size of a wall, and we put masking tape horizontally across it making rows, and then we had all of the issue dates going down a column, and going across we had all of the different departments. So, we really strategized and planned out what our stories were going to be, and you were able to visualize how each issue was going to come together.

Marci Dodds (Music Writer and Editor, 2001 to 2003): I loved everything about working at the Octopus. Working as an editor at a newspaper was something I had always wanted to do, but never thought I ever would. I mean, I didn’t go to journalism school. I didn’t know all the official editor’s marks (some of them, but not all.) I didn’t like scotch or gin. My name wasn’t Ben Bradlee. I did smoke at the time, and could handle Jack on the rocks if it came to it, but I never quite felt those were enough to qualify me for an editor’s position (Yes, I know I had been the editor of a music newspaper, but we’re talking insecurities here, not rational thought.) So I could hardly believe my luck every time I walked in the door.

Jason Pankoke (Production Manager, 2000 to 2001): The Octopus team made me feel at home and as part of something unique in terms of projecting the little-heard voices of our community in an easily accessible format.

Edward Burch (Music Writer and Music Editor, 1999 to 2001): I think of mostly the small, open work atmosphere there, because everybody was in charge of making sure they got their own sections of the paper together for every week’s issue, but then all of us sitting around and looking over everybody’s flats before they went to press.

Marci Dodds: My first assignment was to a writer (Beth Finke) to find out the positives and negatives of live music from the club owners’ point of view. She was — remains — a good writer and a good journalist. She was thorough — and very good at getting people to talk. Club owners, who had never been asked, had quite a lot to say. Even though she was balanced, the upshot of the piece wasn’t “all live musicians are wonderful and all club owners are greedy, bloodsucking pigs.” I think we pissed off every musician in town with that piece — and oh, my. The scathing letters I got! I had wanted to establish the music section as independent and maybe even a little provocative. I think I succeeded. Perhaps a smidge too well. I swear sometimes I think there are musicians in town who are still mad at me from that story.

Holly Rushakoff: [Jenny] helped start the Boneyard Arts Festival. Either the first or the second year, it was just paintings on the Octopus wall. I got some oil paint on my brand new jeans — oops! This painting which Jenny now owns called ‘Mickey Mouse’ or something — this figure holding a gun, and its head is a Mickey Mouse head — and it was in my window.

Doug Hoepker: When we moved into the Lincoln Building, we went from this cramped space into what felt like this luxuriant space, at least in terms of the square footage. We used to shoot nerf guns at each other, and ride bicycles around.

Holly Rushakoff: So, now every time I walk past the Pilates Center [the Lincoln Building’s current tenant], I always think of it as the Octopus. One time someone called to find out where we were located, and I told them the Lincoln Building, and they said that was a cool old building. And I said, “Yeah, it’s got a lot of crooks and nannies in it.”

Doug Hoepker: We knew we sort of had to raise our expectations for where we were going, and we felt a lot more pressure from Yesse! Communications to make money, to turn the corner.

Jenny Southlynn: As Yesse! began to unravel, because it went into its own Chapter 11 [they eventually folded, and I can’t find any mention of them after 2002 -ed.], they were closing papers. They owned a paper in Springfield, they were in and out. Yesse!, they were not in the office, they were in Indianapolis. They would travel and visit us and just wreak havoc around the paper while they were there; made everybody paranoid and they would fire people and do these really draconian things like change the locks on the doors and stuff, you know, stuff that we weren’t used to.

Doug Hoepker: The year 2001, we spent that whole year really on the skids, and not sure if our paychecks were going to cash each time. They were giving us paychecks that would bounce. We would get instructions not to release paychecks until this time of day, or they would instruct us to hold the checks for an extra day. So, it was really tenuous just to keep the doors open. We were always a month or two behind on bills, even rent bills. We owed the printer in Danville lots and lots of money. I think the only reason they didn’t cut us off was that they realized that if they cut us off, they’d have no opportunity to earn that money back.

Jeff Ignatius: I was forced to resign (along with the sales manager) in February 2000. The reason given for my de-facto dismissal was sales performance, but it’s more complicated than that. There were personality issues between me and the paper’s owners, or perhaps more accurately differences of opinion on protocol on certain issues.

Doug Hoepker: [Jeff] was very opinionated, and he put his foot down and said we’re not going to do it that way, and the folks at Yesse! Communications said do it our way or hit the highway. And they both said, “Fuck you,” and they left.

PART IV: THE SAGA SAGA

Jenny Southlynn: So it had all these permutations and the thing was, it just became more and more diluted in terms of its content, its visual impact, because each consecutive owner was trying to find a way to reach that top tier of advertising so that the paper could survive financially. And you know, when you water down your product and you’re not giving people what they want, they stop fucking reading it! And that’s what happened. So it was fated to be — and it’s such a tragedy, because it was such a phenomena in its beginning. Beth Finke wrote for the paper, she was a blind woman and her works were just so compelling; her husband, Mike Knezovich was actually an editor during the Saga years.

Mike Knezovich (Managing Editor, 2001 to 2003): I completed my master’s [in journalism] in the summer of 2001, and I got wind — I’m not sure how — that the paper was for sale. With a friend and his brother, we actually put in a bid to buy the paper. It was modest because when we looked at what was there, not a lot was of value in the business. It was losing a lot of money, its reputation had suffered because of, I think, what was perceived as some shoddy journalism or unfair journalism. I know they’d had trouble meeting payroll more than once, and morale wasn’t great. We took a deep breath and decided to put a bid in, and we learned later that we had been outbid by this Saga Communications, which owns a handful of radio stations there in town [like WIXY-100.3 FM, WCFF-92.5 FM, WLRW-94.5 FM, WXTT-99.1 FM]. They outbid us considerably, I think our bid was something like $25,000 and I think they bid something like $125,000, which we couldn’t really understand, but they did.

Doug Hoepker: They were dipping their toe into the print market for the first time, with the grand scheme that they could corner the market in Champaign-Urbana, sell print and radio in one fell swoop, and make a lot more money with a lot less effort. But Saga had never owned a newspaper, let alone an alternative newspaper, and just didn’t have any idea what they were doing.

Mike Knezovich: Well, they needed someone to be the managing editor of the newspaper, and they retained the old owner to make the transition. Craig approached me about doing the job, and that’s the long story. My official title was senior editor, but in function, it was more like a managing editor, because everything, as I would find out, would fall to me.

Doug Hoepker: I don’t think they wanted to own a paper called the Octopus. I don’t think they felt comfortable selling something called the Octopus. I think they recognized that we had a lot of baggage associated with that name, a lot of negative baggage in the eyes of the advertisers that they wanted to reach. I think they felt the best move was to rename us, but the unfortunate part was that they didn’t involve the staff of the Octopus at all in the renaming process. We just showed up one day and learned that we were going to be called CU Cityview. And everyone was just like “Are you fucking kidding me? That’s a terrible name.”

Mike Knezovich: The biggest problem we had to get over was people not wanting to talk to reporters from the paper. For example, the Urbana school board would not take our calls. I don’t remember the details, but I had a chat with their public information officer, I think, and I said, “I just want to know.” And she said, “Well, two or three times, we’ve just been really burned by things that we feel like you either mischaracterized or got wrong.” And I didn’t agree with everything she said, but some of the things she said, I thought, that was just bad reporting, there was just stuff that was wrong. We ran into that a lot. We ran into this idea that a lot of bridges had been burned, at least in terms of what I thought we needed to be doing.

Holly Rushakoff: One time, our staff came in on a Saturday, I think, and we had a really tall Christmas tree, and we totally strung popcorn together. Maybe more than other places people work, we were friends.

Mike Knezovich: I just came from what I understood to be the values of community journalism, and how neither the News-Gazette or the DI had been filling that need. One thing that really helped us, I think his name is Arthur Culver, had just been hired by the Champaign school district to be superintendent, and he walked into a buzzsaw because of the consent decree, which was still underway and which Champaign was falling behind on executing. He was an African-American, and he was sort of a polarizing figure almost from the day he got there, but I was fascinated by the guy, because I thought in a weird way, this guy has the biggest, toughest job in either town or at the university right now, because it’s really an impossible situation. And maybe because he was new to town, I just started dogging him to sit down for a long interview. We won’t let you edit it, but you’ll say what you say and it’ll find it’s way into print. So Kathy Claar and I got an audience with him, and it was really good. It was something that I was really proud of.

Jenny Southlynn: They just shut it down unceremoniously. People were completely unaware that they were going to lock the doors. They called us all to a meeting and pulled the plug. It was pretty horrifying.

Doug Hoepker: The way I got the news, I was in Chicago with Holly Rushakoff, and we were at this Champaigh-Urbana music showcase that was being held at the Fireside, which was an all-ages venue. I want to say this was the 2nd or 3rd of January. I was in my hotel room getting ready to go to the show, when I got a phone call from Mike Knezovich, and Mike said, “I’ve got some really bad news. The paper has been shut down. This was Saga’s decision and blah blah blah yadda yadda yadda.” He apologized for having to tell me the news in the fashion that he did, over the phone, impersonal, etc., but Saga forced him to do it that way. He had known about this for a couple of weeks beforehand, but was put in the position of “Don’t tell the staff anything until this time.” So, most of the staff wasn’t in the office when they got this news.

Mike Knezovich: The thing that was heartbreaking was that we had gotten through the worst of it. We had gained the trust of people, including the Urbana school board, we’d had a couple of award-winning stories, and people were starting to take us seriously. We had some new life, and what happened was, the Saga Communications people looked at it and said, this is never going to really fly, let alone break even — although we were going to break even that next year. But a company like that doesn’t get involved in a venture like this to break even,

Holly Rushakoff: I was on vacation when they announced they were closing the paper. They packed up my desk for me. They didn’t get everything out. I think I lost a lipstick and a mirror in the drawer, but that’s ok. I had a little notebook of funny things that happened in the office, and that got sealed away, so I don’t know where that went.

Mike Knezovich: I was there into March of 2003, because somebody had to help — ugh, it was awful — kind of bury the body, you know? There were just a lot of loose ends, everything from storing equipment to cleaning out the place, so I ended up employed for 2-1/2 months doing that sort of thing.

Jenny Southlynn: And then I bought it as a partner, along with Don Elmore, Cody Sokolski, Carlos [Nieto], a bunch of local businessmen who wanted to keep something going, and we created The Paper, and that only lasted a year. And it became the Hub and then that just passed away.

EPILOGUE: CITYVIEW AND THE WAR ON TERROR

C.G. Estabrook: I got a call from the FBI a week or two after my farewell column. You know, local FBI office, always looking for something to keep them busy. The FBI guy calls me and says, “The Cityview has received a terrorist letter that mentions you. May we come talk to you about that?” I have a brother who’s a criminal defense attorney, and with years of dealing with police and FBI, the response is always no. But in this case, I was so intrigued, so piqued by the notion of a terrorist letter mentioning me to the Cityview paper, come on! I mean, I don’t think Al Qaeda is working on the Cityview paper. And the FBI guy was so from central casting, like Jack Webb from the old Dragnet show, I called my brother and said, I gotta talk to this guy and see what this is about. And my brother says, Put two chairs in your front lawn and wait for him to pull up and when he does, offer him a chair. Don’t let him in the house, and stop at any point where it look like… So this FBI guy brings me this letter, signed with a fake Arab name, saying ‘We’re so upset about the Cityview no longer running Mr. Estabrook’s column that we intend to blow up a bus full of Israeli children.’ I said, ‘This guy isn’t tied too tight,’ and the FBI guy says, ‘Oh, we take this stuff very seriously.’ Oh, come on. The interview didn’t last too long, because I said it’s an obvious hoax, and I know you guys need something to justify your budget, but this is a little silly — I did not say that, but that was the subtext. And that was the end of it until they busted a kid, broke into his house, seized his computer, a 21-year-old guy called Weissberg, Max Weissberg, whose father, Robert Weissberg, was teaching political science here at the time. Max Weissberg, who is now a filmmaker and had a thing at SXSW, he must be rising 30, and he had written this letter after writing a series of letters under his real name complaining about my anti-Israeli position. They dragged the poor guy into court, and the court took a dim view of it. He was supposed to go off to college at Reed, in Oregon, and the court, after much effort, agreed that he could leave the jurisdiction to go to college, but they reamed him pretty well, and they shouldn’t have. I actually called his attorney and said it’s an obvious hoax and it shouldn’t be treated as anything other that protected political speech. Well, the lawyer thanked me for my legal opinion.

Bottom row: Will Jou, Holly Rushakoff, Jenny Southlynn, Ted Veatch

Middle row: Davee Davis, Kathy Schuren, Laurence Mate, Mike Knezovich, Sam Xu, Kathy Claar

Back row: Chuck Koplinski, Doug Hoepker