It’s been 50 years since 1968: The Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, the first image of the dark side of the moon. The experiences of the year, felt nationally and locally, fueled a persistent sense of loss and gain, a sense of identity that recognized the push away from the old ways of living while still maintaining a loose, pinky finger grip. The unsettled nature of the debate about damage done, victories won, drastic cultural shifts, and what it means to be “American” makes this year as subject so compelling, urgently drawing us to historical parallels in 2018. These are the themes that Museum of the Grand Prairie is exploring in their latest exhibit, 1968: A Time For Every Purpose.

What makes this unique from other museum exhibits that might be similarly reflecting on this year, is that it focuses on more than the events that made national news and the trends experienced at large. Now on view at the Museum of the Grand Prairie in Mahomet, 1968 features the local stories of the people of Champaign County as they both react, influence, and shape the national historical narrative. The exhibit also commemorates the Museum of the Grand Prairie’s golden birthday, highlighting its origin story, archives, and accomplishments throughout the past 50 years.

Each exhibit display tells a story: such as how the height of the Vietnam War was experienced through the eyes of Rantoul native Stephen Douglas, a boat captain in the Coast Guard; or how the political divisiveness of the time might have sparked Musicircus, one the largest Champaign-Urbana “happenings” coordinated by John Cage during his appointment at the U of I. Happenings is a term that is commonly used to describe loose, often improvised arrangements and choreography to encourage spontaneous interactions between the audience and the performers, musical instruments, or objects. Held at the Stock Pavilion, Musicircus looked like a giant livestock judging contest; the performers were placed on raised platforms to mimic the judges while the audience took on the role of livestock roaming around the floor.

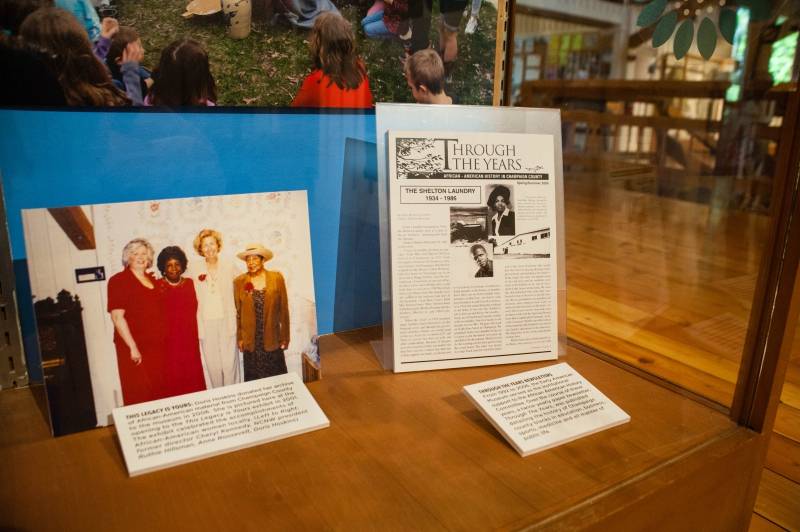

You can’t condense history into textbooks,” said Katie Snyder, Education Program Specialist for the museum. “You will never get the full story, or you will get only one side of the story.” Snyder, who curated the civil rights section of the exhibit, focused on local movements by Black communities for racial equality, all marked after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. Many of these pieces in this collection are from the Doris Hoskins archive. Doris Hoskins was a resident of Champaign, Illinois and long-time friend of the Museum of the Grand Prairie. Throughout much of her life and throughout much of 1968, Doris Hoskins was collecting event programs, underground newspapers, and any and all knowledge, information, and other cultural artifacts that came from the African American communities in Champaign-Urbana. This archive was given to the museum upon her passing in 2004.

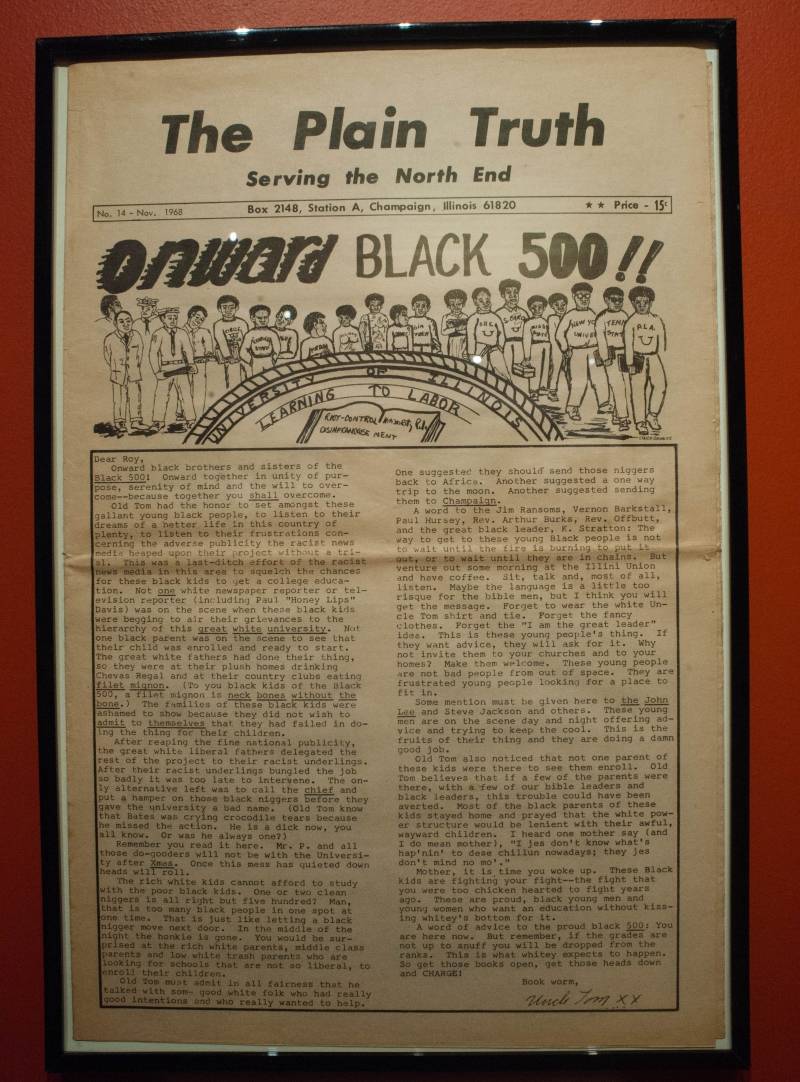

One piece in particular displayed from the Doris Hoskins archive is a front cover of The Plain Truth, a community newspaper produced by and for the African-American community on the north side of Champaign. This edition of The Plain Truth detailed ways the community could support Project 500, an initiative motivated by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. where Black students at the university, the Black communities in Champaign-Urbana, and the university administration launched an effort to enroll 500 African-American students to the University of Illinois. Snyder made a point to mention Project 1000, a current initiative that references the 1968 effort, led today by the Black United Front and other students of color on the campus. The 1968 campaign was a success, tripling black enrollment at the Urbana campus. But, as you learn in the exhibit, African-American enrollment at UIUC has stalled since then.

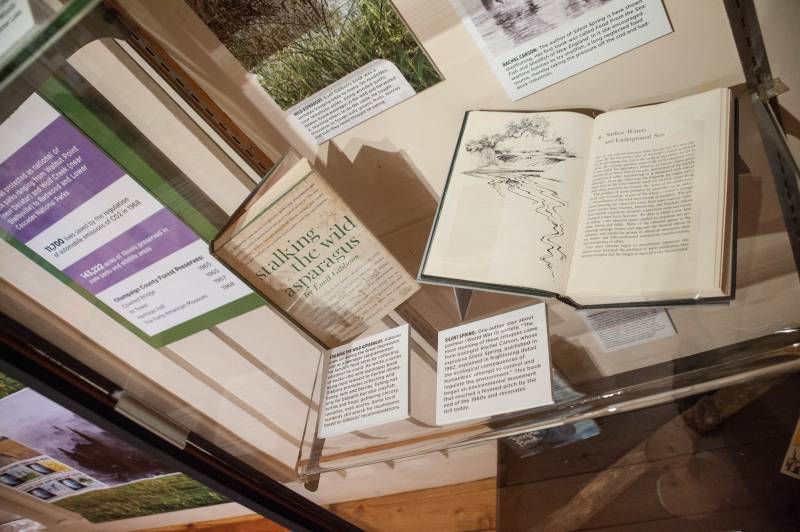

“As you walk through the exhibition, you will begin to draw parallels through some of the events, practices, and trends featured in this exhibit and see them at play today,” Snyder added. In the adjacent exhibition display, we experience the story of how an admiration for the natural world through food foraging practices led to the writing of salient environmental activism works, such as Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, who discovered that DDT pesticide runoff from farms was polluting the streams, poisoning water supply, and destroying the ecosystem. In the glass case adjacent to Silent Spring is a popular foraging book at the time, Stalking the Wild Asparagus by Euell Gibbons. Snyder recalls as a child of the sixties how food foraging was very much a part of her life and how she sees some of these self-sufficiency practices coming back into use today.

“I remember my dad taking us out to forage for wild asparagus. He knew how to find all of the good spots, and loved hunting for all sorts of delicious, culinary mushrooms. He would never tell anyone where his morel mushroom spots were,” recalled Snyder. “Today, I think people are coming back to self-sustainable practices and re-instilling a sense of wonder through the appreciation of nature that drives people to practice environmentally-sustainable habits and get involved in efforts to save the Earth.”

Making another historical parallel, this time in the culture and counterculture section of the exhibit, Snyder points out the iconic image of the Tommie “Jet” Smith and John Carlos, African- American athletes and medalists in the 200-meter sprint at the Olympic Games in Mexico, lowering their heads and raising black gloved fists during the national anthem in protest of white supremacy. The gesture led them to being stripped of their medals. Patrick Cain, Public Services/Visitor Coordinator for the museum, said that he definitely had in mind Colin Kaepernick and other NFL athletes who have taken a knee during playing of the national anthem before before the game kickoff. “I’m really into athletics and sports history,” said Patrick Cain. “I wanted to also feature a historical piece of activism that can be seen at play today with athletes in the United States.”

As the 1968 exhibit description reads, “In tumultuous times, it is helpful to look to the past to understand what we might learn.” The mission of the Museum of the Grand Prairie is to tell the history of the people of Champaign County; and, to experience history not as a series of events but as narratives, the stories of everyday people, making connections from past to present.

“We may have an exhibition about President Abraham Lincoln as one of our permanent exhibitions, but the stories of Lincoln’s travels and visits here in Champaign County is experienced through the primary texts of people who lived here,” said Barbara Oehlschlaeger-Garvey, Museum and Education Department Director. “It is through the telling of diverse experiences of Champaign County that the Museum of the Grand Prairie seeks to inspire our audiences with a sense of connection to, and stewardship of, their natural and cultural world.”

Through the Museum of the Grand Prairie’s early american archives, which included a large collection of implements and primary texts that were donated by William Redman, you get a sense of of life in Champaign County during this time. It is William Redman’s “Pioneer Collection,” that gave birth to the museum in 1968.

Imagine what the Museum of the Grand Prairie’s 2018 exhibition might look like in 2068 and what stories might be told. Anyone can contribute to the archives of Champaign County, and Museum Curator Mark Hanson gives us a tip on personal archiving and collections. “If you hesitate for a bit as you consider throwing anything away, hold onto it,” Hanson said. “Then, give us a call. We will look through your collections with you and let you know if it’s something that we can archive at the museum.”

1968: A Time for Every Purpose will be on view for the public all year long at the Museum of the Grand Prairie from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday-Saturday and from 1 to 5 p.m., Sundays. Be sure to check out the calendar on their website, as they plan to host speakers and special events to bring various perspectives and themes that the 1968 exhibit investigates to new life.