The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is well-known for the achievements of many of its programs. From Engineering to Veterinary Medicine — it is a world leader. It’s also been at the forefront of exploration into electroacoustic music for the last 60 years. Beginning in the late 1950s, forward thinking musicians and researchers at U of I began examining the ways that electronic and acoustic elements could be combined to create new sounds and sonic possibilities and facilitate the musical interaction between humans and machines.

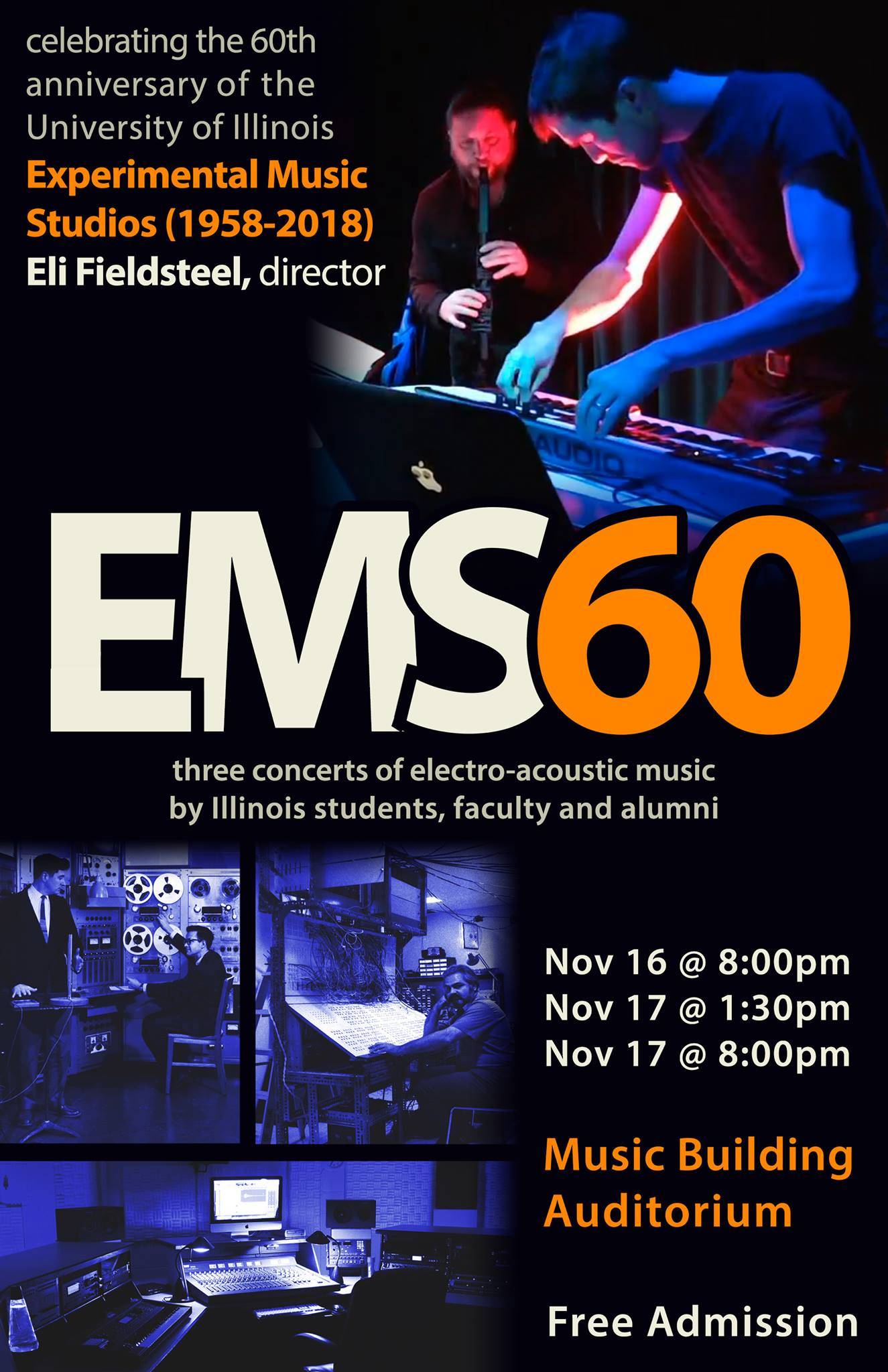

Tucked away on the top floor of the Music Building are the Experimental Music Studios, a collection of six, flexible studio spaces that cater to the needs of musicians and researchers and stand as a testament to the university’s history of innovative and creative music making. This weekend, the University of Illinois School of Music will be hosting a two day series of concerts to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Experimental Music Studios.

I sat down with current EMS director, Assistant Professor Eli Fieldsteel, to talk about the history of the EMS and the upcoming anniversary festival.

Smile Politely: Can you tell us a little about yourself and what you do at UIUC?

Eli Fieldsteel: Sure. This is my third year at U of I. I am an Assistant Professor of Composition-Theory and I am also the Director of the Experimental Music Studios. In that capacity, I teach upper level courses on electroacoustic music covering beginning, intermediate and advanced topics in that area. I also compose and lately my composition projects and research have been focusing on exotic control schemes.

SP: Very cool. Prior to reading about the EMS at 60 concerts, I had no idea that the University of Illinois Experimental Music Studios (EMS) existed. What are they? Based on the name of the festival this weekend, I’m assuming they’ve been around for 60 years? How did they begin?

Fieldsteel: This morning, I considered inviting the former director of EMS, Scott Wyatt, who has been at the university for 40 years to come talk. He would be an infinitely better person to ask this question to [laughs]. He knows the history in and out and I’ve gleaned bits and pieces.

It’s now plural — studios — but it began as a single studio. The Experimental Music Studio, singular, was founded in 1958 by Lejaren Hiller. He was a chemistry scholar and had an interest in music and the emerging field of electronic music or using electronics to create music. There was some money received to found the studio, but not much. I think a lot of the gear was just sort of cobbled together from stuff that other departments were throwing away. Kind of like junkyard discoveries. So that’s how it started.

In there beginning, there was a lot of instrument building. One of the first analog synthesizers was built here. That was James Beauchamp’s “harmonic tone generator”. And one of the big, early happenings was Lejaren Hiller’s string quartet composed by computer, a very old, primitive, large computer with physical logic circuits.

Eli Fieldsteel

SP: I didn’t realize that the university had been involved in researching and creating electronic music for so long. How has the role of the EMS changed over the years?

Fieldsteel: So, from the early 60s until today, there have been a few different directors. Herbert Brün was the director for a while and Salvator Martirano. Scott Wyatt became the director in the mid-70s and he was the director up until 2016.

As the years progressed, it became clearer and clearer that the merging of electronics and music was inevitable and now it’s completely inseparable. The original studio was located in a building that no longer exists anymore. But, there are six studios now, on the top floor of the Music Building.

SP: Why is having six experimental music studios on campus important?

Fieldsteel: Well, it’s more than most schools. Many schools will have a fully modernized studio space for recording and production and creative research. Most will have more than one. But, we’ve got a suite of six and they’re very flexible. I’ve re-designed three of them since I got here, sort of changing out software and hardware components, trying to better serve students, guest composers and researchers and practitioners who come here. We try to keep things up-to-date to be able to cater to any sort of project you might imagine pursuing as someone who is interested in computers, electronics, and music.

SP: Is there a distinction between an “experimental music studio” and a “traditional” music studio?

Fieldsteel: No. My understanding, or at least what I’ve been telling people, is when the experimental music studio was founded, using computers and electricity to augment the music creative process was extremely experimental. It was experimenting with music. And nowadays, that kind of facility is called an electronic music studio because it’s not at all experimental [laughs]. Now it’s kind of weird to not use a computer.

SP: Following up on the last question, can you tell us a little bit about the upcoming festival? Who will be performing? What will they be performing?

Fieldsteel: Sure. Scott Wyatt, who ran the program for 40 years, is still here as an Emeritus faculty member and I knew the 60th anniversary [of the EMS] was coming up and I wanted to do something to celebrate the significance of EMS while Scott was here. So, 9 or so months ago, I put out a call for works to a few big electronic music listservs and various organizations asking for works. I indicated that priority would go to individuals who have official affiliations with the University of Illinois and, preferably, the Experimental Music Studios. And I got a huge response, something like 300 and I was able to accept almost all of the alumni submissions. I think we have 3 or 4 pieces by current students, one piece of Lejaren Hiller, who will open the Friday concert, a piece by Scott Wyatt, which will be the final piece of the last concert. The rest of it is, I think, all alumni, spanning the past three decades. I think it will be really cool.

SP: It sounds like almost like an EMS retrospective! What kind of pieces will be performed?

Fieldsteel: There will be a couple of fixed media pieces, where it’s just a predetermined audio file where all of the gestures and sounds are “baked in” to the audio file. Some of them are 8 channel pieces, so you’ll be sitting in the auditorium and there will be sound coming from eight different speakers all around you. And then there are pieces with live elements, either a live performer or someone performing on controllers. There’s a laptop improvisation, there are pieces with live video processing. It’s a good mix and I am really looking forward to being regaled with stories of EMS so I can actually learn more about the history and that one time that something caught on fire [laughs], you know. Whatever the stories might be. It’s a huge program, it’s one of the oldest programs in the U.S. And from humble beginnings, we’ve grown quite a lot.

SP: Throughout the program information for the festival, the term “electroacoustic” pops up. What does the term mean?

Fieldsteel: Sure, yeah. Electroacoustic music is somewhat of a fluid term, especially to people who are active practitioners. When used in the phrase, “electroacoustic music”, it refers to music which has electronic elements and acoustic elements. And this can take different forms. It can be an acoustic recording which has been electronically processed. It can refer to a piece which involves an unprocessed live performance and a computer simultaneously generating sounds. It’s a pretty loose term, all things considered.

All “chart toppers” undergo rigorous mixing and mastering process, which is all computer aided. But that’s not what we consider electroacoustic music. No one would call the latest, uh, Cardi B, “electroacoustic music”. You’d call it “pop music”. Electroacoustic music refers to what most people would call “academic music”, something that has an experimental angle to it. Something which has a research component to it, something where you’re studying a particular aspect to sound and discovering things and then working them into a creative composition that can be presented or performed.

SP: The idea of academic music and studying sound might be a little hard for some people to conceptualize. Are there any musicians whose output you’d point to as embodying this type of music?

Fieldsteel: There are so many names to pick from. I would definitely put Elainie Lillios at Bowling Green University on my list. And certainly Scott Wyatt. He’s got tons of very masterful electroacoustic compositions. Jeffrey Stolet at the University of Oregon. And Paul Koonce who will have the penultimate piece in our festival.

SP: For a lot of people, “electronic music” conjures up an almost unintelligible, inhuman cacophony of beeps, bloops, scratches and glitches and is generally an unapproachable kind of expression. For others, it a fertile vein of underexplored creative possibility and potential that both reflects and is shaped by humanity’s relationship with technology. What is electronic music to you? Why should people care about it?

Fieldsteel: To me, I just really enjoy creating sounds using computers. It’s an activity which I feel I’ve become very adept with. I’ve gotten to a point, it’s taken a long time, but I feel like I can now imagine a sound and with the hardware and software at my disposal and with the skills I’ve acquired, I can get very close [to creating it], which is cool.

I come from a family of math professors. My parents are both math professors and my brother has a PhD in Math. I was a double major for a while. So, I’ve always been good at analytical thinking and this is just a perfect blend for me. And with a programming language like Supercollider, it’s like I have a third arm and I can do things that people with two arms can’t do [laughs].

But that’s the value it has for me. And I don’t feel nearly as comfortable asserting why it has value for other people because it very well may not. And that’s fine. Some people think of techno and house when they think of electronic music and some people think of bleeps and bloops and a synthesizer just playing by itself in some studio somewhere making the weirdest sounds ever. There are a lot people who have no interest in [electroacoustic music] and that’s fine with me. I’m gonna keep making pieces and write papers and disseminate discoveries and teach and interactive with people who share those interests.

SP: Final Question: why should people come to the festival? As they walk out at the end the performances, how might they expect to feel?

Fieldsteel: It will not be a traditional concert, but it will be very exciting. You’re gonna hear some things that you’ve never heard before. Types of sounds that you wouldn’t expect to be on a concert. So, you should come if you are the adventurous type and you want to hear some new stuff that you may not have ever imagined in your wildest dreams.

The EMS at 60 Festival starts tonight, Friday, November 16th at 8 p.m. It continues tomorrow, November 17th, with shows at 1:30 p.m. and 8 p.m. All shows are free and take place in the Music Auditorium Building.