At 7 a.m., people start lining up to get bread and pastries still warm from the ovens of the bakeries in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana, Illinois.

At 7 a.m., people start lining up to get bread and pastries still warm from the ovens of the bakeries in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana, Illinois.

The local diners have already sent their first wave of customers on their way, stomachs full of pancakes, waffles, and omelets to fuel the tasks of plumbing, wiring, and brick laying. By 10 a.m., the members of the laptop crowd have commandeered the tables of the local coffee shops, and are busy fleshing out characters in novels and writing new subroutines. This is the Silicon Prairie, after all. Between 10 and 11, the hum of the downtowns will be pierced by the whistle of a train pulling dozens, sometimes hundreds of cars of grain grown on the surrounding farms.

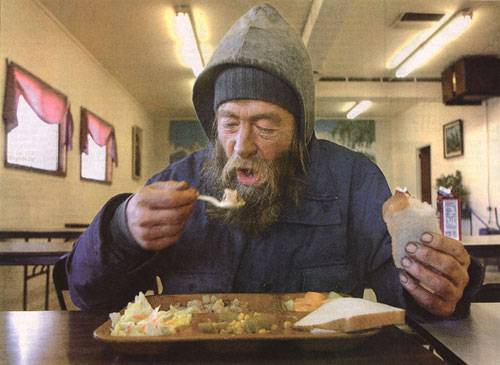

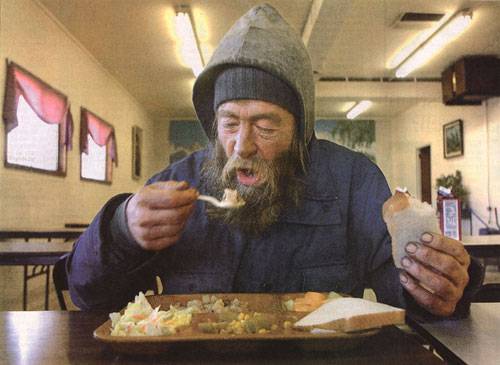

For all the world, Champaign-Urbana looks like a prosperous community. But sometime before noon, the illusion shatters. That’s when the line starts to run out the door and around the block at the Daily Bread Soup Kitchen just a few blocks from the center of downtown Champaign. Shortly after four, there will be another line forming in front of the door of St. Patrick’s food pantry on Main Street just a few blocks from the center of Urbana. And, if it is the third Thursday of the month, hundreds of people will file into the Wesley United Methodist pantry on the campus of the University of Illinois between the two downtowns, hoping their numbers will be called so they can fill their empty cupboards.

Despite being surrounded by some of the most productive farmland on earth, people are hungry here. Statewide, one in six children is at risk for hunger, but in East Central Illinois, the number of children who are food pantry clients is one in three. And it’s about to get worse. By the end of 2010, the number of homeless children in Champaign schools will have increased by 72 percent in just three years, predicts Barbara Daly, Assistant Superintendent of the Regional Office of Education for Champaign and Ford Counties.

Each week, food stamp case workers routinely violate case load limits just to dent the situation. Of those residents who receive assistance, some must resort to trading it on the black market to meet their family’s equally important needs for medicine — even if it means losing their food assistance forever.

To address the gaps in federal food assistance programs, local agencies and organizations are taking fresh fruits and vegetables into schools, providing food for children when schools aren’t feeding them, putting farmers markets in low-income neighborhoods, converting unused property into produce fields, and expanding the hours of pantries so that they can serve the working poor.

But feeding those who are hungry only solves part of the problem. Adults who are hungry experience higher levels of depression. Children in impoverished homes experience more anxiety, more respiratory illnesses, and more obesity due to the higher cost of nutrient-dense calories. Young children in poverty also are more at risk for cognitive development problems.

What’s working? What’s not? And what can we do as individuals to help keep our neighbors fed and healthy when federal programs aimed at doing so are failing so miserably?

How did we get here?

Hunger is invariably tied to stable jobs and housing. Employers like the University of Illinois, Carle Hospital and Clinic, Champaign Unit 4 Schools, Kraft Foods, Parkland College, and Provena Covenant Medical Center, are a big part of the reason that Champaign-Urbana has fared better than some downstate communities when it comes to unemployment. However, Carle had to layoff 93 workers in 2008. In November 2009, the University of Illinois notified all employees making above $30,000 annually that they would need to take unpaid furlough days in 2010 so that the institution could balance its books in lieu of the $500 million in payments owed to it by the state.

By the close of 2009, consumer belt tightening, layoffs, salary reductions and freezes resulted in a $5.17 million dollar shortfall in Champaign-Urbana’s retail economy according to the Illinois Department of Revenue. This made an already tough job market even tougher. Just two years earlier, the community’s annual unemployment rate was running at 4.4 percent according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. By 2008, it had climbed to 5.7 percent. In 2009 it nearly doubled, reaching 8.2 percent. This year, it has climbed higher still, averaging 9.5 percent. By the most recent Census estimates, this means just under 10,700 residents are presently out of work.

Less than 40 miles away, the industrial city of Danville is running a 13 percent unemployment rate. However, this isn’t the first time its unemployment rate has skyrocketed. The city took a serious hit in 1993 with the closing of a General Motors foundry and ran double digits during the mid 1980s, as well.

Despite its track record of stable employment or perhaps enabled by it, Champaign-Urbana is second only to Danville for extreme poverty rates in Illinois, outranking Chicago, East Saint Louis, and Rockford. These residents live at below half the poverty rate–less than $11,025 of household income for a family of four. Champaign-Urbana’s overall poverty rate is estimated to be at 19.5 percent, far ahead of Chicago Metro’s 12.7, according to the latest data from the Social IMPACT Research Center at Heartland Alliance.

This level of poverty puts a premium on temporary and permanent low income housing in the community, both of which have waiting lists and gaps in services. Though Champaign and Urbana have emergency shelters for single men and single women with children, options for entire families are very limited and made headlines in 2009.

In May of 2009, the owner of Gateway Studios, a former Holiday Inn converted to apartments, defaulted on payments to the utility company Ameren. With no gas or electricity, the City of Champaign was required to condemn the complex, which caused over 100 people, including some small children and disabled individuals, to become homeless.

A few months later, St. Jude Catholic Worker House and St. Mary’s Catholic Church defied city leaders by inviting the residents of the Safe Haven tent community to illegally camp on their properties during the summer and early fall as this allowed many of the families in the community to live together instead of being separated at local shelters. In November, the families and individuals of Safe Haven were offered temporary housing for winter by Restoration Urban Ministries in west Champaign until the cities of Champaign and Urbana could come up with more permanent options.

However, the homeless and those in extreme poverty are not the only ones whose food situations are in question, or as those in the field term it “food insecure.” Despite common perceptions, the majority of those receiving food from local pantries actually have jobs. Unfortunately their paychecks can no longer cover rent and increases in utilities, food, fuel, and medication. Many are forced to make impossible choices between these, often with food losing out.

Next: Trying to Keep Food on the Table

This piece was crowd-funded by Smile Politely readers through a collaboration with Spot.us. You can read this story on Spot.us and read the list of contributors here. Thanks to Spot.us, and our generous readers. Let us know if you have an idea for an investigative piece (that you or someone else could report on) that you’d like to see us pursue.