William Roper: So, now you give the Devil the benefit of law!

Sir Thomas More: Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?

William Roper: Yes, I’d cut down every law in England to do that!

Sir Thomas More: Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ’round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man’s laws, not God’s! And if you cut them down, and you’re just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake!

(A Man for All Seasons)

By now, most of you know what happened to Dr. Kenneth J. Howell. The News-Gazette has done a pretty thorough job reporting this story. For those who haven’t heard, here’s a quick rundown:

By now, most of you know what happened to Dr. Kenneth J. Howell. The News-Gazette has done a pretty thorough job reporting this story. For those who haven’t heard, here’s a quick rundown:

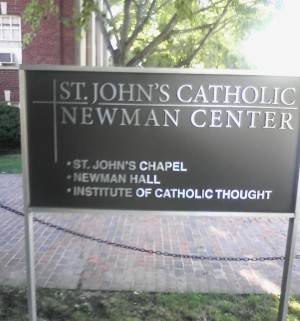

Until this summer, Dr. Howell was the Director & Senior Fellow of The Institute of Catholic Thought at St. John’s Catholic Newman Center at the University of Illinois. He was also an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Program for the Study of Religion at U of I. Howell has been with the Newman Center since 1998, and he’s been teaching Introduction to Catholicism and Modern Catholic Thought at the U of I since 2001. He’s both a minister and a college instructor, and it seems that recently the two hats he wears got crossed.

On May 13, 2010, a friend of one of Howell’s students sent an email to Robert McKim (head of the religion department), complaining that Howell was teaching that homosexuality is immoral. This is true; Howell had sent an email to his class that states that homosexuality goes against Natural Moral Law (NML), and is therefore unhealthy, unnatural and immoral. In his complaint, the author called Howell’s email “hate speech,” and he forwarded it to McKim. This resulted in Dr. Howell being told that he would not be welcomed back to teach at the U of I after the spring semester. He was effectively fired.

I’ve read the friend’s complaint. And I’ve read Howell’s email to his students. Both cause me huge concerns. I was raised in a strict, Catholic household, and I’m queer, so this is personally important to me. I’ve also taught English, Composition, and Rhetoric at the college level, so this is intellectually important to me, as well.

Before I read Dr. Howell’s email to his class, I first read the complaint by the student’s friend. He said that he is neither gay, nor a gay activist, so his anger and distress at what Howell (right) had written is especially honorable. But is he angry at what Howell said? Or is he angry that his own beliefs (and those of his friend) regarding homosexuality are being challenged? From his email: “Teaching a student about the tenets of a religion is one thing. Declaring that homosexual acts violate the natural laws of man is another.”

Before I read Dr. Howell’s email to his class, I first read the complaint by the student’s friend. He said that he is neither gay, nor a gay activist, so his anger and distress at what Howell (right) had written is especially honorable. But is he angry at what Howell said? Or is he angry that his own beliefs (and those of his friend) regarding homosexuality are being challenged? From his email: “Teaching a student about the tenets of a religion is one thing. Declaring that homosexual acts violate the natural laws of man is another.”

As I said, I was raised Catholic. As a matter of fact, the tenets of Catholicism actually declare that homosexual acts violate the natural laws of man. It may sound like “hate speech” to some (it surely does to me), but it’s strict Catholic doctrine. Howell was teaching a course on Catholicism, and everything he said in his email is true in regards to what the Catholic Church says about homosexuality (excuse me, “homosexual acts”):

Basing itself on sacred Scripture, which presents homosexual acts as acts of grave depravity, tradition has always declared that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered. They are contrary to the natural law. They close the sexual act to the gift of life. They do not proceed from a genuine affective and sexual complementarity. Under no circumstances can they be approved” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 2357).

And let’s not forget this guy.

So, the hard truth is that Catholicism teaches that people in same sex relationships are unnatural, immoral, and live outside of God’s law. And if Howell was discussing moral law in the context of Catholic doctrine, and homosexuality was brought into the discussion (as his email fully states it was), then he was doing nothing wrong in explaining the Church’s position on the topic and the reasons behind it.

I also read Howell’s email, and the context of why he felt the need to write it is important, and it’s something that I think has been lost in all of the emotion surrounding what happened. Howell was trying to prepare his students for their final exam. In a recent lecture on utilitarianism and Natural Moral Law (NML), the class seems to have gotten off-topic, and began discussing homosexuality and morality, a discussion that Howell considered “incomplete” in the context of the larger issues of utilitarianism and NML. Howell wrote that there would be a question on utilitarianism on the exam, and he wanted to bring the class back on-topic: “I realized after my lectures on moral theory that even though I talked about the substance of utilitarianism, I did not identify it as such and so you may not have been able to see it.”

He then takes their previous discussion on “the morality of homosexual acts” and uses it to demonstrate the Catholic Church’s views on utilitarianism and NML. And surprise, surprise, the Catholic Church thinks homosexuals are sinners. Who could have seen that coming?

I’ve come away from this controversy with two main questions:

- Given the course itself, given who Dr. Howell is, what did these students think they were going to hear in this class?

- What is so terrible about a professor challenging his students’ beliefs and ideologies?

#1. Howell was teaching a class on Catholicism. This wasn’t a philosophy class, or a comparative religion class, or even a theology class. If it was, I’d feel very differently. It was a class on Catholicism. What in the world did the students think they were going to be learning? Did they not research this class at all before they signed up for it? Or Dr. Howell, himself? Did they not research the Institute of Catholic Thought? A quick keyword search of “Homosexuality” in its library holdings will tell you everything you need to know about its views on LGBTQ people.

#2. I loved teaching. But each semester, with a few exceptions of course, I had to talk my students down from a ledge when it came time to write research papers. I required them to address the counter-argument to their theses, and this was something they struggled with mightily. It wasn’t just because they found the assignment intellectually difficult. It was because they didn’t like having to think about — or treat with respect — the “other side’s” opinion. When they would address it, they’d attempt to either blow it off in a sentence or two, or treat it as ignorant or . . . immoral.

I’m not sure when it happened, but students no longer expect to be challenged by their teachers. And they’re not happy when they are. I’m not talking about the challenges of learning facts and writing papers and studying for difficult exams. Rather, far too many students vehemently eschew the aggressive intellectual inquiry that I’ve always thought a good college education must have, especially if it’s a liberal arts education.

The humanities demand vigorous, dialectical debate if we’re to understand anything at all. A classroom should be a place for challenging our most precious values and ideas. It’s a place that is supposed to cultivate and welcome debate and discussion. A classroom should rarely be intellectually comfortable. Getting a classical education should always be difficult, fulfilling, enlightening, sometimes frightening, oftentimes infuriating, and always, always engaging.

In college, I heard the following paraphrased statements from my professors:

- “Why couldn’t Cordelia just give in? Why couldn’t she swallow her pride and say what her father wanted her to say? That’s the way daughters were supposed to behave back then.”

- (qtd. Churchill) “If you’re not a liberal at 20 you have no heart, if you’re not a conservative at 40 you have no brain.”

- “Some believe that the entire universe was once the size of a man’s fist. Some will believe anything.”

These statements were made to get us thinking, to make us care, maybe to make us a little angry, to provoke us out of our complacency. And I wrote some damn good papers in response to those statements. Maybe my professors were serious; maybe they weren’t. Maybe Howell was serious in his email (likely), or maybe he was trying to engage his students, and encourage them to think about these issues (unlikely) — issues that clearly made at least one of them uncomfortable. But what is wrong with being made uncomfortable in the classroom? Isn’t that supposed to happen?

The student’s friend writes: “I can only imagine how ashamed and uncomfortable a gay student would feel if he/she were to take this course.” I have every reason to believe that his feelings are sincere, and I do appreciate them. And I especially appreciate his use of proper pronouns (he/she, instead of “they.” Yay parallelism!). But I digress…

As I said, I appreciate this gentleman’s empathy for his gay classmates, but in no better place can gay young adults learn to defend themselves than the college classroom. A good, liberal education teaches us to correctly define our terms, spot logical fallacies, such as red herrings and straw man arguments (and Howell’s email has them). It’s in a classroom setting, just like this one, that a gay student could shine. And Howell’s email gave him all the ammunition he’d need. The only way we will achieve our full civil rights in this country is through our intellects, and I find it disheartening and not a little frightening that many students today expect to avoid intellectual and ideological challenges in the classroom.

I found Howell’s email vile. Hurtful. Infuriating. Ignorant. He comes off as not only a homophobe, but also sexist and transphobic, as only Catholic doctrine regarding homosexuality can. And Howell is nothing if not a parrot for his Church. Moreover, the fact that every single one of Howell’s examples focused only on gay men is very telling. Very telling, indeed.

I found Howell’s email vile. Hurtful. Infuriating. Ignorant. He comes off as not only a homophobe, but also sexist and transphobic, as only Catholic doctrine regarding homosexuality can. And Howell is nothing if not a parrot for his Church. Moreover, the fact that every single one of Howell’s examples focused only on gay men is very telling. Very telling, indeed.

Unlike the young man who wrote that email, I am a part of the LGBT community. And, unlike him, I am a gay rights activist. And I have no doubt that Howell believes everything he wrote. I don’t like being in the position to defend such a man. I hope to never meet him in person. I wouldn’t shake his hand if I did. But my feelings have nothing to do with whether or not he was doing his job. He was teaching Catholic doctrine as it is today. At the time of this writing, there is no evidence that he was violating his students’ rights.

I wasn’t in the classroom. I don’t know Howell’s history as an instructor at the U of I. He’s been with the Newman Center for over a decade, and he’s been teaching for nine years. Have there been past complaints about his lectures? Does he grade fairly? Has his grading ever been challenged? From his email: “All I ask as your teacher is that you approach these questions as a thinking adult. That implies questioning what you have heard around you… All I encourage is to make informed decisions [sic].”

As long as “questioning what you’ve heard around you” includes what they’ve also heard from Howell, then I see no problems here. Yes, he was overzealous; he was preparing them for their final exam. Why didn’t these students “fight” him in their essays and exams? Why didn’t they debunk his weak, ignorant arguments? That’s what college is for.

That being said, Howell’s decision to give his class a final lecture (and that’s clearly the intent of his email) in the format that he did was incredibly disrespectful to his students. In a proper classroom setting, they would have been able to respond. With email, they were forced to read (listen), but had no chance to engage in the conversation. That was a thoughtless decision on Howell’s part. But worthy of firing? After working here for over a decade and receiving two recognitions for excellence?

Professors must have intellectual freedom in the classroom (especially nontenured ones). Those who value academic freedom and the free expression of ideas have to see that a dangerous precedent has been set (many religions hold the same doctrines about homosexuality as Catholicism does). Cary Nelson (right), president of the American Association of University Professors, states that professors are free “to share their beliefs with students” and to “advocate for a particular position.” From his email — and this is all we have to go on for now — Howell has acted appropriately.

Professors must have intellectual freedom in the classroom (especially nontenured ones). Those who value academic freedom and the free expression of ideas have to see that a dangerous precedent has been set (many religions hold the same doctrines about homosexuality as Catholicism does). Cary Nelson (right), president of the American Association of University Professors, states that professors are free “to share their beliefs with students” and to “advocate for a particular position.” From his email — and this is all we have to go on for now — Howell has acted appropriately.

As far as I can tell from the News-Gazette‘s article, there have been no complaints against Howell concerning unfair grading, and he states that “penalizing [students] for their beliefs” is something he considers “injurious.” He also said that he’s used to students disagreeing with him, and until now it’s never been a problem. In fact, Howell even allows that his word isn’t Gospel: “If what I just said is true…” Again, there is no evidence that the students’ rights were being violated.

If Howell is telling the truth, if his students “are never required to believe what [he’s] teaching and they’ll never be judged on that,” then this can be proven by researching his past grading practices. If he’s found to be guilty, then yes, fire him. But if not, discipline him for his infamous email and let academic freedom ring.

It’s gratifying to learn that straight students and faculty are offended by bigoted, homophobic beliefs. But far too often we fail to differentiate between advocacy and activism. LGBTQ college students don’t need protection from hateful ideas, quite the contrary. Learning to intellectually refute hateful ideas is important and necessary. A classroom is not supposed to be a safe haven from hateful ideas. Students are supposed to feel uncomfortable sometimes. Analyzing what’s made us uncomfortable, or afraid, or offended, or angry, and then taking the time to understand it, challenge it, and finally come to a conclusion — oftentimes not the one we expected — that’s what education is.

The best thing for LGBTQ students — and all students — is to be torn from their comfort zones, and to learn how to rationally and intellectually respond to that experience. Perhaps the best place to do that is on the bloodless battlefield of the college classroom.