Last winter, looking for a rest stop off the interstate south of Pueblo, Colorado, my family came across a small picnic park with a monument to the victims of the “Ludlow Massacre,” a bloody 1914 incident that occurred during a standoff between striking miners and the National Guard. In the end, 20 people died, including many women and children who suffocated in underground bunkers when the army set fire to the strikers’ tent city. You can actually walk down into the cellar where the victims perished. Eerie, yes, but perhaps even more uncanny is how abandoned the park felt, surrounded by miles of sagebrush and open desert. Somewhere there is a history book about 1914, but this story probably isn’t featured. It’s like floor 7½ in the film Being John Malkovich: the place in-between stories. The monument that nobody sees.

Last winter, looking for a rest stop off the interstate south of Pueblo, Colorado, my family came across a small picnic park with a monument to the victims of the “Ludlow Massacre,” a bloody 1914 incident that occurred during a standoff between striking miners and the National Guard. In the end, 20 people died, including many women and children who suffocated in underground bunkers when the army set fire to the strikers’ tent city. You can actually walk down into the cellar where the victims perished. Eerie, yes, but perhaps even more uncanny is how abandoned the park felt, surrounded by miles of sagebrush and open desert. Somewhere there is a history book about 1914, but this story probably isn’t featured. It’s like floor 7½ in the film Being John Malkovich: the place in-between stories. The monument that nobody sees.

Monuments are in themselves bereft of meaning, in spite of the sometimes heroic efforts spent in their creation. Monuments only mean something when we give them meaning, and believe me, some monuments are super-charged with meaning. The Lincoln Memorial, for example, is so laden with received meaning that the plaza directly in front is considered hallowed ground, and those speakers who have taken the podium there are blessed and sanctified by the monument’s proximity. Imagine the shock, then, of tourists when last year I tried to haul one of my cranky, travel-fatigued kids over to the spot where Martin Luther King gave his “I have a dream” speech and my cranky kid screamed, “SO WHAT???”

After I died of parental shame, I considered his point of view. Could it be that he has a point? The pavement itself, its small gold plaque, is not all that important. It is the story we tell ourselves about that place, that monument, that makes us travel across the continent to be there. Our American identity is at stake, and the monument tells a story that we want to be true.

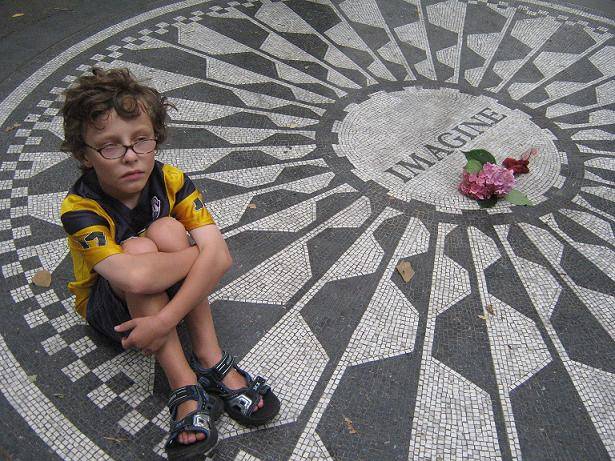

But the relatively new “Imagine” memorial up the way in Central Park, across from the Dakota apartment building where John Lennon was killed, is fast becoming a popular pilgrimage site. A woman from Louisville leaves a note on the memorial: “John, I love you and miss you”. A couple speaking German leaves white carnations. This memorial tells many stories, but especially the one about hope and the power of imagination. Americans like that one, especially if you leave out the part about banishing religion.

The National Park Service has three warehouses to store the gifts left at the Vietnam Memorial. Once, a veterans group left a brand-new tricked-out Harley Davidson for their fallen comrades.

But veterans in Wichita, Kansas refused to allow a new monument honoring South Vietnamese allies who died in the Vietnam War to be placed in a veteran’s memorial park. After much debate, the monument will be placed at the edge of the park, a mound-wall separating it from the others.

Floor 7½. A lost story. A monument that nobody sees.

I am searching for these lost monuments. Because I believe what we deny, forget, cast out, is what sometimes reveals the most about us.

Ludlow, Colorado is a ghost town. In central Illinois, Mount Olive to be exact, only a few short miles from the monument marking Lincoln’s grave, there is another cemetery monument, this one tended to by a league of retired women dedicated to preserving the memory of Mary Harris Jones, better known as Mother Jones, who was almost single-handedly responsible for the creation of laws protecting children and factory workers in the early part of the industrial age in America. In guidebooks, this monument is mentioned after the paragraph about the oldest gas station still in existence on historical Route 66.

There are no tourists here. No flowers, Harley Davidson’s, tour guides or related fanfare. Evidently, the Mother Jones monument isn’t a story we really want to hear. At one time, she was called the most dangerous woman in America. She led marches, influenced politics, and lost her entire family to yellow fever. What is it about powerful, resilient women that often, not always, relegates them to monumental obscurity? Better to be an imaginary woman like the  Statue of Liberty, welcoming the tired and the poor to a nurturing bosom.

Statue of Liberty, welcoming the tired and the poor to a nurturing bosom.

Mother Jones was in Ludlow, Colorado just a few days before the firestorm. She was an agitator, a morale-lifter, a radical, and most likely bolstered the strikers’ resolve in the days leading up to the tragic confrontation. In the end, the strike and its aftermath eventually forced John D. Rockefeller Jr. to improve working conditions in the Colorado coalmines.

Before I had ever read the story, I knew she had been there. I knew it because of the remoteness of the place and the stories of women still hiding under the ground.