This is…Champaign-Urbana!

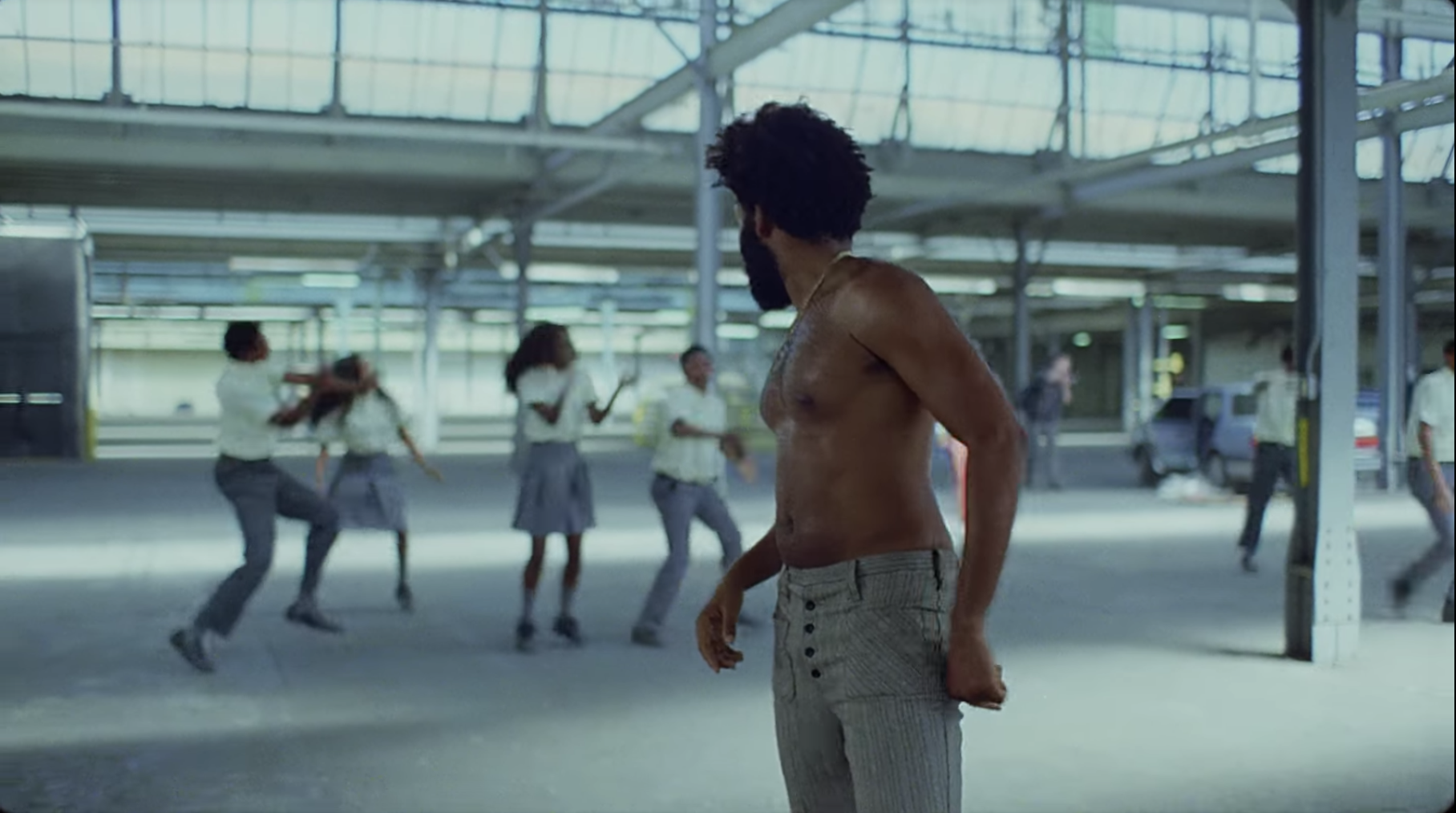

I am sure many of us have been reflecting deeply on many aspects of Childish Gambino’s video for his song “This is America,” but the youth dancing in the video is what is most profound to me. The dancing felt so familiar. Where had I seen the striking juxtaposition of children dancing through the violence before?

Then, I remembered.

The youth dancing in Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” reminded me of Champaign’s very own Central High School cheerleaders dancing to “Let’s Get It Started” to open the January 2018 Gun Violence Forum sponsored by the Unit 4 PTA. Like the youth in Childish Gambino’s video, Central High School students — black girls — were asked by the Unit 4 PTA to dance through their terror a month after the December 2017 shooting at the Central-Danville basketball game.

Yep, those parallels are chilling to me all over again.

More chilling still is that from the Central High School shooting through the spring 2018, local reporting continued to chronicle actual violence and threats of armed violence in local schools across East Central Illinois, including Champaign, Monticello, St. Joseph, Mansfield, Cerro Gordo, and Niantic:

- December 9th, 2017: Three Hospitalized After Shooting Outside Central High School

- February 15th, 2018: Middle Schooler’s Threat Prompts Hoopeston Area To Increase Police Presence

- March 9th, 2018: Student Found With Stun Gun At Jefferson Middle School

- March 13th, 2018: Edison Student Removed From School Over Snapchat Message

- April 2nd, 2018: Since Florida shooting: 14 threats of violence at area schools

- April 23rd, 2018: 7 Facing Charges In Chaotic Situation At Centennial That Sent 1 To Hospital

Central High School students participating in the National School Walkout in March.

Central High School students participating in the National School Walkout in March.

Despite these incidents — and plenty of others that are unreported — as summer approaches, I continue to encounter adults who speak of local school climate in hushed tones. “Nicole have you heard….” as the volume of the speaker drops when recounting the incident. Or, “Nicole, you know there was a meeting recently where…”…speaker’s voice falls to hushed tones when detailing the latest school concern.

Consequently, as we are preparing for summer heat, closed schools, unoccupied, under-resourced, and underserved youth with gun access or gun-fueled fantasies, the conversations about the potential for more gun violence barely registers with the public.

There are two fundamental questions that keep plucking my nerves:

- What are we going to do as a community to calm our flailing, hemorrhaging children?

- When do we find the time to figure out why our children hate themselves, each other, and us?

In her trauma trainings and work with C-U Peace and Resiliency Champions, Karen Simms challenges us to reconsider our interactions with others by moving away from focusing on “what a person has done or is doing” that might be negative, and instead asking “what happened to them?”

As we prepare to launch an array of summer camps, programs, and projects, it is crucial to have youth programmers consider whether they can answer the following questions for each young person they are preparing to serve, regardless of race, class, gender, faith, or location across our community:

- What is the most pressing problem or concern on the child’s mind this summer?

- How likely will it be that they arrive hungry? Do they have access to balanced meals and fresh food whenever possible?

- Will this program include recreation, activity, downtime, exercise, fresh air, safe spaces for play and renewal for the child?

- Is the child sick? Are their injuries, illness, and growing pains creating discomfort?

- How has their school year been? Did they enjoy school, or was it just another space of surveillance, judgement, and anxiety for them?

- Have they been bullied and are they being bullied now?

- Is there anyone abusing drugs or alcohol at home or where they live?

- Have the children been involved in or witnessed incidents of violence this year?

- Is their home or residence “hoarded out” and filled with clutter, trash, and/or animals?

- Are there unsecured weapons in the home or current residence?

- Are they homeless? Do they currently have residential instability?

- Do they have relatives that are deployed or serving in the military?

- Has anyone touched them inappropriately this year? Recently? Ever?

- Conversely, do they receive healthy, appropriate touch, affection, or encouragement on a regular basis?

- Are any of their relatives in jail or incarcerated?

- Does this program offer opportunities for parents/caretakers to feel welcome or be involved in summer activities?

- Are parents or caretakers working multiple jobs and rarely present?

- Does the child feel that they can communicate and be heard by the adults in their lives?

- Are parents present, but too consumed with work or technology to be fully present when they are with the child?

- If the child is stressed, bored, or anxious, how do they typically deal with those feelings?

- Does the child have prayer, meditation, or stress-relief practices by which they can steady themselves and/or manage anxiety?

- Has the child lost loved ones to death this year?

- Have loved ones moved away from the child this year?

- Does the child or youth believe someone owes them an apology that they have never heard?

- Do they owe an apology to someone else?

I know these questions may feel extremely intrusive, but they are the kind of questions that we must be willing to consider, and we must consider remedies for responses given, if we are to have any hope at getting to the core of why our children are so aggravated with themselves, each other, and us. The above are some of the questions that I hope we are considering as we are planning for youth programs, projects, and camps. Be sure to add your own pressing questions to this list.

Adults: We must shift some of the burdens of these questions raised back onto adult shoulders. Children across our community are being crushed under the weight of dealing with the questions themselves.

I believe grappling seriously with the answers to the questions can inform the kinds of programs and interventions we offer to fortify our children as they grow.

If we as adults are not willing to take responsibility for the harm that we inflict, or allow to be inflicted, on our children (intentionally or unintentionally at an interpersonal and institutional level), we can expect nothing but continued violence to come to our individual selves, our institutions, and communities.

Screenshots from Childish Gambino’s “This is America” video. Photo by Julie McClure.