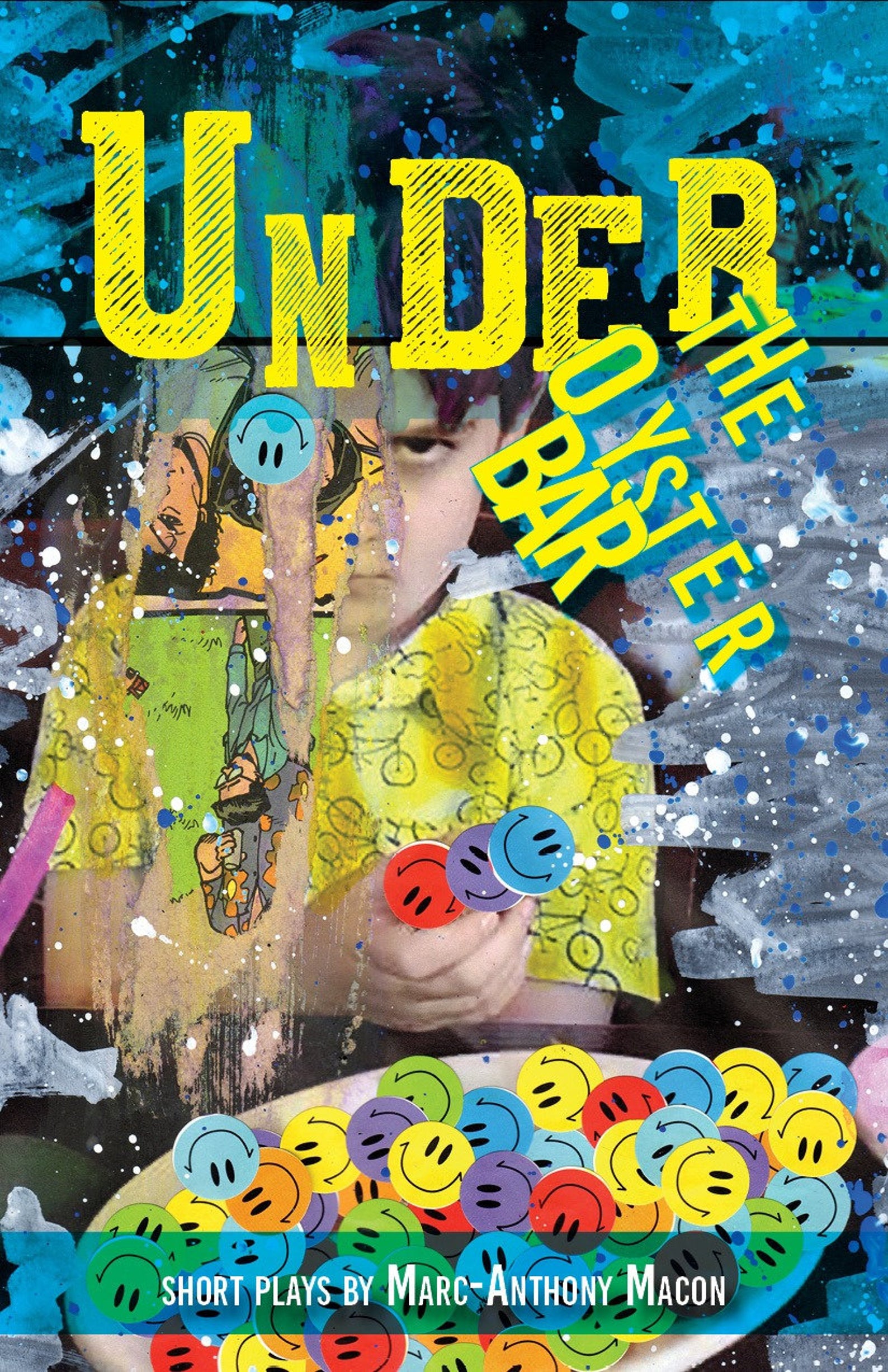

At a time when “reality” becomes more “unreal” each day, you might as well as say screw it and take a deep dive into some seriously Surrealist literature, where the unreality is intentional and a lot more fun. And Under the Oyster Bar, a self-pubilshed collection of short plays created by Urbana-based mixed-media artist and writer Marc-Anthony Macon, should be at the top of your reading list.

Under the Oyster Bar is like a box of chocolates. Not the Forrest Gump kind. And certainly not the waxy rot you find in heart shaped boxes in February. It’s like eating small batch, artisanal chocolates made in brave new combinations like cinnamon chili, whiskey truffle, or edamame sea salt. It challenges your senses and creates new pathways in your brain.

And as with a box of chocolates, there are several different ways to consume it. You can start at the beginning and work your way through to the end, doing so either with willpower or with willful abandon. As the various flavors emerge, you can choose to experience it as a continuous work [several characters do find their way into more than one play], or you can savor each morsel as its own unique universe. I have preferred random selection, where you can either go to the table of contents, close your eyes and point. Or spin the pages between your fingers and embark on the story you land on. For me, this approach feels truest to the spirit of Surrealism, or its forbearer Dadaism. Just give yourself permission to experiment. Think of it as training, or untraining, your mind to open itself to non-traditional reading experiences.

In his brilliant introduction to the book, writer and performer Noah Diamond observes that entering “the Macon-verse” is “more like being blindfolded and pushed into the pool,” that pool being “filled with koosh balls and Udon noodles and barking lobsters.” And yes, the “Macon-verse” is a thing and we need to spread the word, if for no other reason than to replace the now fallen-from-grace creator of another -verse, with a brilliant and kind queer artist.

There is a wonderful playfulness at work in this collection that reminds me of playing Mad Libs. But then again, the apparent randomness is far too artful for mere accident. In the opening play, “Dark Matter and Menthols,” Marla enters a truck stop at the edge of the void. Through the windows are a dusty cliff top and an endless black chasm. Marla tries to get the attention of Clark, a clerk intently counting the rows of cigarettes behind the counter. She requests lottery tickets, menthols, and a lighter. They talk about how taxes on cigarettes have gone sky high. Marla admits it doesn’t really matter anymore. She then asks him if he “appraises” the customers who come in. If he wagers “will he jump, or is he a chicken?” Clark answers that he sees the truck stop as a “train station,” where people “go from one place to the next. Not my business, really.”

As the true purpose of Marla’s errand becomes clear, a reader finds herself flashing back to the beginning and realizing that yes, it had to be a truck stop at the edge of the void. And it had to be cigarettes that Clark is counting. Clark himself suggests the trope of a man offering a last cigarette to the victim of a firing squad. Both participant and distracted witness, as if he were the one wearing the blindfold. If I were to read more into this, and maybe I shouldn’t, I would argue that Clark embodies our conflicted sense of connection to each other’s suffering. But I could be wrong. Sometimes a barking lobster is just a barking lobster.

Image from the author’s Etsy site

If you like your Surrealism short and sweet, you’ll find a number of plays here that fit the bill. Perfect for a break, or a bit of before-bed reading, which, if you’re lucky, will inspire some fantastic dreams. Among the briefest of the bunch is “The Rise of Butternut Squash,” which I share below.

[A throne, bejeweled, cased in crushed black velvet and gold trim. A bored and ineffectual KING sits on the throne with a wayward look on his face. GUARDS stand on either side. A BUTTERNUT SQUASH sits in the middle of the throne room. Long silence.]

BUTTERNUT SQUASH

Now, my minions![ASSASSINS zip into the throne room, stab both the GUARDS and slit the throat of the KING. They cheer, then reverently pick up the BUTTERNUT SQUASH and place her on the throne.]

BUTTERNUT SQUASH

Now, bring me the DVDs of the entire run of “All My Children,” apes![Curtain.]

When I interviewed Macon earlier this year, I asked if he would “like to see them have a second life on stage someday?” He responded in true form, saying that he would “surely love to see someone try to make an evening of performing these short plays, and [he] would wish them the best of luck, and maybe recommend a variety of professionals that might offer them moral, legal, or psychological reasons that they should reconsider. I revisted the question again while reading Noah Diamond’s introduction, where he shares the following:

“These plays are like poems for the stage. They defy the impulse to imagine literal stagings as we read them. But I think they should be staged. It would be too easy to imagine them on film, where Marc-Anthony’s fantasia could be realized literally — but at some cost to its magic. This playwright has issued a challenge, and it should be taken up by a theatre director of comparable nerve. In our virtual age, analog media like print and theatre may be the only forms which can still fully embrace the power of this imagination, which is what Marc-Anthony’s work requires, of us, as well as of him.” —Excerpt from Noah Diamond’s introduction to Under the Oyster Bar.

At present, I find myself arguing against literal staging. Part of the magic of this work is that each reading is unique. To continue with the food metaphors, Macon provides the recipe, but the reader’s imagination, with all of its unique associations and experiences, provides the secret ingredient.

While most readers (in our previous interview Macon advised against sharing the book with your gran) will find their own favorite moments, Urbana residents are sure to enjoy the local references in “Crane Alley Convalescence” and “Asha Bhosle, Meredith Monk, and Teddy Ruxpin at the Broadway Food Hall.” In a “which five people, dead or alive, would you most want to have dinner with” style, Macon engages with a cast of cultural icons, including Lorca, Dalí and Rothko. While the collection makes it impossible to chose one favorite, this reviewer holds a special place in her heart for “The Giving Tree Gets Help.” Is it really any wonder that all those years of giving, giving, and more giving, have led her to the therapist’s couch? The resulting encounter takes on the value of Freudian analysis in the face of basic, lower-rung Maslowian needs.

Perhaps one of the greatest joys of the book is Macon’s portrayal of queer characters. As Diamond observes in his introduction, “the lovers in his work are typically gay, but their sexuality is never overtly the theme.” Macon “posits a world in which characters are queer by default, then simply writes about love.”

Never missing an opportunity to tease us with a good Easter egg, Macon concludes with a story meant to inform, or upend, our understanding of the book’s title.

There’s an oyster bar in a train station in a city I love. If you get to know the right folks there (and if they especially dig you) they’ll show you how to go underneath the place, where there’s a whole world of these little players, each wanting to be adopted like it’s a theatrical orphanage. You can dust ’em off, put ’em in your pocket, take ’em home and raise ’em into family. The raw half-shell special comes highly recommended. — excerpted from the author’s “Outroduction.”

After my journey Under the Oyster Bar, part of me wants all books to include an absurdist addendum that makes you reconsider everything you just read in a new way. Or as writer “Oscar Wilde” writes in his back cover blurb, “It was so clever, I didn’t understand a word of it.”

Winter is the right time to curl up with this collection and “welcome these little players” into your imagination. Your imagination will thank you.

Order Under the Oyster Bar from the author’s Etsy site (for a signed copy), or on Amazon

Follow Marc-Anthony Macon on Tik Tok, Instagram, or Etsy