As a kid in the 1970s, I used to hang out during the summers at the original oval Crystal Lake Swimming Pool in Urbana, a pool built in 1927 and designed by architect Joseph Royer. As a teenager, I went to Urbana High School, which was built in 1913 and designed by Joseph Royer. As an adult, I served jury duty at the Champaign County Courthouse, built in 1900 and designed by … well, you get the idea.

I’m mentioning my links to the designs of Joseph Royer ― who was active as an architect during roughly the first half of the twentieth century ― not because they’re unique connections, but rather because they’re not unique; everyone living in Champaign-Urbana has some kind of connection with the buildings Royer designed. While many of his structures have been lost, many are still standing: The Urbana Free Library, The Traction Building in Champaign, the Urbana Post Office that’s now the Rose Bowl Tavern, Leal School, the historic Lincoln Hotel, and more.

Urbana High School

Who was this guy?

His buildings are still all around us in C-U, but who was Joseph Royer? Well, he was born in 1873 in Urbana. He went to Urbana High School, and then to the U of I, earning a degree in architecture in 1895. He began his career as an architect in the late 1800s, and also served as Urbana’s city engineer from 1898 to 1906. He was married in 1902. He lived for decades at 801 West Oregon Street in Urbana. He designed buildings until the 1950s, locally, around the Midwest and even a few beyond that ― there’s a Royer building in North Carolina. He died in Urbana in 1954 at the age of 81.

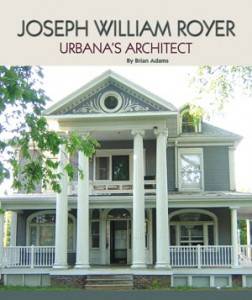

But what was he like as a person? That’s a question Brian Adams, Assistant Director of the Public Service Archaeology & Architecture Program at the U of I, attempts to answer in his book Joseph William Royer: Urbana’s Architect, published earlier this year by The News-Gazette. I spoke to Adams recently about his book and about Joseph Royer’s life, work, and times.

But what was he like as a person? That’s a question Brian Adams, Assistant Director of the Public Service Archaeology & Architecture Program at the U of I, attempts to answer in his book Joseph William Royer: Urbana’s Architect, published earlier this year by The News-Gazette. I spoke to Adams recently about his book and about Joseph Royer’s life, work, and times.

Adams, who lives in historic Urbana, became curious about Royer through trying to learn more about his own neighborhood. Once he started researching, Adams discovered that much about the architect ― who was well known locally in his day ― had been lost over the years. Adams said:

I had bought an old house in Urbana, and, as I was researching it, I became interested in who built it. So I started looking in the archives and going through old newspapers. I had heard about Royer ― he was well known, obviously ― and I was finding a lot of details about his life. But he was sort of a shadowy person to me. An 1895 school photo was well known when I started my research, but I found no adult photos of him at first. I’d never seen a picture of him as an adult. He was a member of the Elks Lodge, and in 1910 they had their big annual conference in Urbana. As part of the newspaper story, they had little portrait photos of all the members, and there he was, from 1910. So, slowly, I began to pull together all these pieces. I found out what he looked like. I found out he was big into hunting. He was into hunting dogs. He was well known in town. He was like the football coach is now. People would keep an eye on what he was up to, and things he did would be in the newspaper.

Much of the information in Adams’ book comes from old, local newspapers and archived records. I asked Adams how successful he was in finding living links to Royer. He replied:

I had some limited success, but that was more recently, when the book came out. Some of it I was able to take advantage of in time to get it in print. For example, a lot of pictures of some of his wife’s family ― those ultimately came from tracking down descendants of his sister-in-law who no longer live in this area. I found that they still had photographs and family stories to tell. I was able to tap into those, to a degree.

Adams found another link during the successful attempt to gain landmark status for the Lincoln Hotel last winter:

There was one case when there were City Council proceedings going on regarding the landmark designation for the hotel Royer designed. One of the people who spoke said his father was there. So the father got up to speak, and he must have been 80, 90 years old. He remembered the funding drives from when he was a child ― it was supported by community stock ― and he would refer to ‘Joe Royer.’ He must have been really young at the time.

Lincoln Hotel

Adams ended up learning quite a bit about people related to Royer ― the impression I got from Adams’ book is that he may have even discovered more about Royer’s relatives than Royer himself. Adams told me:

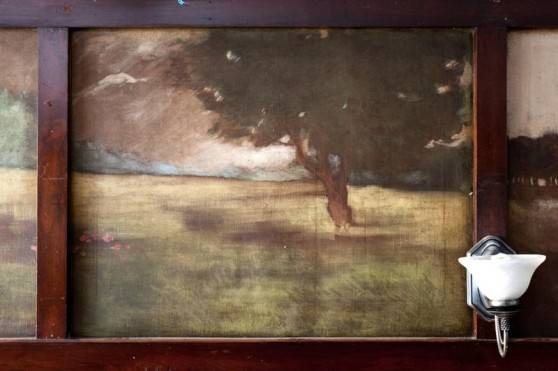

Another thing that was interesting, in Royer’s own residence on Oregon Street in Urbana, I always heard that there were murals painted on the wall. I eventually was able to get a good look at them, and I contacted an art gallery in Santa Barbara, California, because I heard that his sister-in-law became a well-known artist out there. So I went back and forth with the gallery ― The Sullivan Goss Gallery ― and they were pretty convinced that the murals in Royer’s house were by the sister-in-law. She did a series of paintings of the California Missions and was very active in the arts and crafts movement. But when the Royers died here, that connection to a famous artist was kind of forgotten.

Nell Brooker Mayhew Mural

I asked Adams about business records and things of that nature ― after all, Royer was a prominent businessman in the community for decades. What about a paper trail? Adams responded:

Before Royer died, he was in the middle of changing his will, and he never signed his new will. So, a lot of his papers and property, I think, were destroyed. So, I think there were some things that happened near the end of his life that explained how he just sort of disappeared.

Royer lived his whole life in Urbana. I wondered whether he was a townie by choice or circumstance. Did he stay here because after a certain point his business was too established to leave, or was he emotionally invested in Champaign County? I asked Adams to speculate, and he answered:

I think he felt comfortable here. His father had worked at the mill downtown. His wife’s family was still here in town and he participated in the Elks Lodge. He was active locally. He had family here. I think that once he established himself here, he knew he would always have work.

He traveled a lot. He had projects in northern Wisconsin, one in North Carolina. His sister-in-law lived in California, and he and his wife took trips out there. There are stories of him taking hunting trips in Southern Illinois. So he went out of this community, but he always came back. I never got the sense that he really wanted to get out of this area.

The book

Adams told me that he didn’t intend to write a book about Joseph Royer when he began researching him:

I had been collecting stuff since about 2000, but I just had a notebook and I’d jot things down for reference. It wasn’t until about three years ago that I realized I should pull this all together. It just kind of took on a life of its own. I found the information about his parents; I had all this information about his sister-in-law. I thought this would be a nice biography. From there it took about three years.

Day by day I’d go through the old newspapers to research it. I was going through the microfilm, just kind of page by page at the library. About two thirds of the way through my research, they came out with a digital version of the newspapers, which made things a lot easier.

One of Adams’ favorite Royer buildings is the Freeman House at 504 W. Elm Street in Urbana. Discovering that the house was designed by Royer inspired him to continue researching:

The house is just a few doors down from me on West Elm Street. It’s a favorite of mine because I always admired this building, but a couple of years ago it became threatened with demolition. I didn’t know anything about who had designed it. It was a rental at the time. I researched it and found out it was built for a guy named Gus Freeman who was married to one of the Busey family. Gus Freeman eventually owned and operated the theater in Urbana now housing the Cinema Gallery. He started out his career as a train engineer. He had kind of a colorful history himself.

But anyway, he built the house, and when I was researching it, I found this little two line reference that Gus Freeman was going to build a house at this address and Joseph Royer was drawing up plans. I nearly fell out of my chair ― I said, ‘Oh my God, that’s a Royer house.’ So I think for that reason it kind of became a favorite of mine. It was one that wasn’t recognized as a Royer house.

Freeman House

Success and innovation

Adams writes in the introduction to his book:

A traveler entering Urbana in the 1920s might well have been entering a city justifiably named ‘Royerville.’ By that time, much of the architectural character of downtown Urbana and much of the residential ring around the city had been determined by Urbana-born architect Joseph William Royer.

Adams then goes on to list some of Royer’s buildings that were standing at the time: the Urbana Country Club, the remodeled Leavitt factory, the Champaign County Almshouse, The Champaign County Jail building, and more. Adams attributes some of Royer’s domination of the local architectural scene (although he wasn’t the only successful local architect) to him being personable, as well as a good mixer and networker. Also, according to Adams, Royer was generally reliable and consistently provided good results.

I asked Adams if there was ever a “prestige factor” attached to owning a Royer building, if people ever wanted Royer to design a building for them in the same way people today want a purse from a certain designer just for the label. Adams replied:

I think he was known as a person you could get good results from. I don’t know if it was a status thing at the time, like, ‘Oh, I’ve got a Royer house.’ He would do things like barns. So, I don’t think a farmer would say, ‘I’ve got a Royer barn;’ they just knew that they could get a good product.

Basically, Royer took on many projects just for the work, and Adams believes there are more unidentified Royer buildings ― including some pretty humble ones ― out there. “I’ve pulled together about 125 projects. So in 50 years, he had to have done more than that. I’m sure he did a lot of barns, a lot of everyday stuff,” Adams said.

Adams points out in his book that many of Royer’s best known buildings are, to some extent, copies of other structures. The Champaign County Courthouse, for instance, was likely inspired by the design of a courthouse in Pennsylvania. Other Royer designs, however, are more original ― for instance the Eastern Illinois Memorial Sanitarium, built in 1924, that later became Carle Hospital.

Eastern Illinois Memorial Sanitarium

So was Royer more of a good implementer of existing design concepts or an innovator? Adams responded:

I think he was a little of both. In general, he was following the trends that were common at the time. Obviously, he was doing what people wanted and expected. But there are cases like with the hospital, where they had asked him to come up with some design, and he came up with the Y-shaped building. That was pretty unique; he was coming up with something they wanted, but he could stray away from the cut-and-dry. I think he was creative in that sense, he was able to get beyond, ‘OK, a hospital is a rectangular building.’

One thing too that I’ve noticed is I can go by a house now, and even though it looks like five other houses on the street, I’ll think, ‘There’s something different about that one, I’ll bet that’s a Royer.’ And it’s always hard to put a finger on it. I’ll remember the address and try to research it. And sometimes I’m wrong.

After World War I, a lot of soldiers coming back from Europe brought back ideas for homes. And they were seeing things like French Chateaus, and that was common at the time ― if you look around there are so many houses that have the beams and the stuccos from that period. But there was a movement that started in California where they went a little bit beyond that. They used those same elements but made it almost fairy tale like. These buildings had things like arched doors; they had just a little bit more of a whimsical treatment to them. I think Royer was able to take existing templates of, say, a Tudor building or a French building and design it through the lens of what he was seeing in California ― because that’s where this sort of fairy tale style started ― and he probably saw these buildings when he was visiting his sister-in-law who lived there. I think he was able to jump on that movement and show his own signature. Not just, ‘OK, now we’re making Tudor-Revival buildings.’ He was able to embellish them.

A good example of that is right on Lincoln Avenue. There’s a sorority house on Vermont that I think is currently vacant. The entranceway is like a turret. But if you look at some of the details ― some of the shingles on the roof are kind of wavy; they’re not square. ‘Whimsical’ is the word that they always use for that kind of thing.

Zeta Tau Alpha House

Preservation and appreciation

Adams is active in preserving older local architecture in general and Royer’s buildings in particular. He told me, “Not all houses can be saved, but there are some that are worthy at least of our interest historically or architecturally.”

One reason he wrote a biography on Royer (this is the first one) is in case it’s ever needed in the future to help justify preserving a Royer building. He said:

People know Royer was an architect here, but by kind of pulling together what is known about his life, he becomes more of a real person ― what he looked like, what his family was like. I think by doing that, more of an argument can be made that he was a significant person in the community, that he contributed a lot. He was recognized as being very skilled in his profession. He wasn’t just a small town architect; he was getting projects in Iowa, Wisconsin. This is the kind of information that needs to be pulled together in one place, so in a year, five years, or ten years, if a Royer building is threatened with demolition, this will help. If it’s a case where there’s controversy ― Can it be saved? Is it a unique enough part of our cultural history to save? ― then this book could help. That was probably the driving force to write the book, so that there could be a biography answering the question: who was this guy?

In my conversation with Adams, he made several references to his research being part of a larger, ongoing historical effort:

One of the projects I’m working on now is talking to people to see if we can pull together some sort of Royer exhibition, where we bring together these surviving perspective drawings and blueprints. It would be good to bring things together, but again, he’s kind of this shadowy guy. He’s a recognized name, but when you actually see the blueprint of something he’s drawn, you really get a sense that he had a big operation going.

Adams said that blueprints and other things Royer left behind are out in the community in various places, and that items are still being rediscovered:

It’s kind of a patchwork. There are some people who have houses, and through talking to people I’ve been able to look at some blueprints. I found some really nice three-dimensional watercolors Royer did of buildings. One of the fraternity houses that he designed ― it was for the architectural fraternity over by the Armory ― published an article. There are some of those floating around. The Urbana Free Library has its full set of blueprints for the original library that Royer designed ― they’re incredible to look at; you can see all the detail. They’re rolled up on paper.

There was a big brick building right off Main Street that was a rare surviving World War I armory, and one recently discovered set of blueprints was for that building, and it was signed ‘Royer.’ It was built around 1916 for a cavalry unit.

A lot of documents ― if they exist ― are scattered, but things like blueprints show up unexpectedly in old buildings. There’s a lot out there; it would be really nice to pull it all together for a temporary exhibit or if the Archives could dedicate a room to this stuff.

As for his own book, Adams said it’s basically a work in progress: “I may have to do a second volume.”

In conclusion

I asked Adams if he learned more about Royer the man or Royer the architect through writing his book. He replied:

I think I learned a lot more about the man, especially his wife ― she was involved in interior decorating, and she had this incredible sister who was well known out west. So I think I was able to somewhat recreate them and learn a little bit about what they liked. He liked hunting; he liked pool and he was good at it. Little bits and pieces. Not a full profile, but he became more human. Not just a name on a cornerstone.

The newspapers would write a lot about what he was doing, but I never found him blowing his own horn. I got the impression that the Royers lived in their house and pretty much kept to themselves. He talked to people; he knew things. She was really active in University things, but I think they pretty much lived their lives and didn’t want to be in the spotlight.

In the last line of his book, Adams writes of Royer and his wife, “their spirits are alive in Urbana today.”

How so? Adams put it this way to me:

I think part of it, obviously, is that his buildings are still here. His house is still here along with the murals ― which is a really personal link with his wife’s family. So the point I was trying to make is that everything is still here, if you look around for it. The architectural look of the community is always changing, but we can still find their footprints here in town. It takes time and patience, but it’s just a question of dusting off everything that happened since they departed this world and now.