For non-dancers, ballroom dancing typically calls to mind one of two images: 1) Dancing with the Stars, meaning men in tailcoats and women in sparkly dresses and feathers, or 2) the kind of dancing your grandparents did. Anyone who has been fortunate enough to witness Alex Tecza and Kato Lindholm perform would know that ballroom dancing clearly has more to offer. The same-sex ballroom pair are truly remarkable to watch, as I detailed in my recent review of their two performances at Dance at Illinois Downtown.

Although in recent years Tecza and Lindholm have become popular fixtures in the Champaign-Urbana dance community, neither is originally from the area. Tecza was born in Poland and moved to Champaign as a junior in high school and graduated from Urbana High School. Although he started dancing ballroom at his high school in Poland, he went on to graduate with a degree in microbiology from the University of Illinois and worked at Abbott Labs for ten years while developing his dance career on the side, before eventually making the switch to a full-time dance career. Lindholm got an earlier start on his dance training since his parents owned a dance studio in Denmark (his mother recently celebrated her 80th birthday with her students, whom she still teaches weekly!). He did his first competition when he was five years old, although he says he’s not sure “how much it really looked like dancing.” Lindholm moved to Champaign with Tecza several years ago after previously residing in Chicago.

As a ballroom dancer myself, I’ve been familiar with Tecza and Lindholm for several years now. I first met them when I enrolled in a summer ballroom workshop hosted by Illinois Dancesport, the competitive ballroom dance team at the U of I. A year ago, I decided to return to my own ballroom dance roots, and started taking private lessons with Tecza, with the goal of competing again in Pro-Am; a category at ballroom dance competitions that allows students to compete in a pair with their professional dance teacher, against other student-teacher duos.

For those who have seen Tecza and Lindholm perform together around C-U, you likely knew you were witnessing something special, but perhaps did not realize how special. Tecza and Lindholm have known each other and danced together for more than two decades. But it was a rule change in 2019 finally allowing same-sex couples to compete together in mainstream ballroom dance competitions that allowed them to compete as a same-sex professional ballroom couple. They are North American Same-Sex Champions in the Rhythm (Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero, Mambo) and Smooth (Waltz, Foxtrot, Tango, Viennese Waltz) divisions.

I recently sat down with Tecza and Lindholm to learn more about that monumental competitive debut, how they challenge gender roles in a highly-gendered dance form, and what it is that makes ballroom dancing so appealing to so many people.

Some responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: Ballroom is obviously historically very gendered — it’s only quite recently that it’s been allowed professionally to dance as a same-sex couple. You were really one of the first, if not the first couple to compete professionally, correct?

Alex Tecza: We have to make a little correction. There is an organization called North American Same-Sex Partner Dance Association, and that is the organization which mostly deals with non-traditional couples: same-sex couples, reverse-role couples…

Kato Lindholm: Basically, any two people who want to dance together. They don’t distinguish.

Tecza: So, I don’t know how long this organization has been in existence, but there have been same-sex couples for a long time. But it was not until September 23, 2019, where the rule changed that the mainstream organization allowed professional same-sex couples to compete. The amateur organization had already allowed them.

Lindholm: But not that long before. They kind of saw which way it was going and decided to step on it and allow [the same sex couples].

Tecza: But I think it’s fair to say we were one of the first to compete professionally after the rule change.

SP: Was it challenging? Were you nervous about the response you would get?

Lindholm: I think when you are going against what is perceived to be the right or proper thing, you want to do good, not necessarily good in the sense that you want to win, but good in the sense that you represent yourself and the cause well. So yeah, I think there was a little bit of nervousness, but also a little bit of, “let’s go out there and show them.”

Tecza: There was an article written about our first competition debut and it was titled “The World Didn’t Come to an End.”

SP: [laughter] Good title!

Tecza: So yeah, the response was positive to our face. But I watched some videos on YouTube, and someone asked the judges what they thought, not about us specifically but the rule change, and some judges said they wouldn’t know how to judge it because in their mind only men can be leaders and women can only do the follower’s part.

Lindholm: Well, when you are trained that this is the look we are going for, anything that steps outside of that feels jarring. Some people will respond and say “cool,” and other people will really dig their heels in and say “no, no, no, this is too different.” So, I don’t know if they are opposed out of principle or if they just don’t know what to do with it.

SP: How do you experiment or play with or challenge the expectation of clear (male) lead and (female) follow as a same-sex couple? Do you try to incorporate lead/follow swapping? More side by side work?

Tecza: Our style of dance is completely androgynous. We don’t assign roles whether it would be two men, two women, a man and woman. It’s about two bodies dancing together, and it’s all about how to make the dance work between two bodies. So, in the choice of choreography, and the way we portray the movement, we don’t really get into assigning roles or gender to movement. It’s actually quite interesting to see someone who is quite masculine do something that is considered feminine but not be perceived that way. So, it opens up a completely different dimension that judges have not seen or considered before. But now it’s in front of them.

Lindholm: It doesn’t really make sense that [a couple being same-sex] should matter because as teachers, teachers are always dancing with both people in the couple. There is a lot of same-sex same-gender stuff going on; it’s totally normal, no one bats an eye. And yet suddenly, when it’s put on a public stage, we have to adhere to a different standard. It strikes me as strange that we have that switch going on in some people’s minds. Because even in social situations, you often see people dance together in all kinds of combinations of couples. But for some reason when you have to judge it, it makes a difference?

Tecza: One of the things we also did when competing was change roles or change holds seamlessly. Typically, a man has a certain hold and the woman adjusts to that hold. So in the middle of a movement, we would change holds in way that wasn’t always even perceived.

SP: Do you think the competitive ballroom world is moving towards more acceptance for same-sex couples or challenging traditional gender roles in the dances?

Tecza: Unfortunately, there is still bias from the judges. I do think the initial shock has worn off.

Lindholm: I think there is the possibility that a really good couple could go far. I don’t know if they are ready to let them be champions. But I could see somebody making it to the finals in a major competition. I don’t think there is that much resistance to it.

SP: It’s interesting that ballroom in general is starting to loosen some of those “rules.” I can recall the entire time I was competing in the early 2000s, there was a single routine where a woman had her hair down. Now there is more hair down, there are tattoos. Are there other changes you would like to see in the ballroom world?

Lindholm: I would like for people to not look the same. There is a sense of streamlining, it’s not required; but you see what the winners do, and you copy. And I would like for people to develop more individuality across the board, whatever kind of couple you are in.

SP: Obviously I met the both of you through the U of I’s Dancesport team, how long have you been coaches for them; that’s mostly you Kato, right?

Lindholm: Just about ten years.

SP: Are non-students allowed to join the classes?

Lindholm: Of course! Everyone is allowed. It is mostly U of I students, but everyone is welcome.

SP: Besides private lessons, where else do you teach? What ages? Do all of your students compete?

Lindholm: For ages, mostly from late teens all the way until you can’t dance anymore. There is absolutely no pressure to compete, but it is encouraged because it is good for the learning process to have something to prepare for. But some students really do it for the sake of learning a skill or for the social aspect of it.

SP: Are there any memorable or favorite projects you have worked on recently?

Tecza: There is a continuous collaboration with one of the professors in the dance department, Rebecca Nettl-Fiol, with whom we have been working for about a decade now, using the technique of ballroom dancing and some somatic work that she is the creator of, and a lot of principles of what she does is what we do in ballroom. So, this is what brought us together. She choreographed a few pieces where we contributed a lot of our own knowledge and ballroom expertise, and we just recently performed at The Virginia [Theatre], sort of a reprisal of Jacques Brel suite from the past that was done for the first time ten years ago.

Lindholm: I also think the Paso Doble/ Flamenco show that we just did for Carnaval! Mostly for the process though because it was so frustrating, but it was fun.

SP: Where is your favorite place to perform in Champaign-Urbana?

Tecza: Krannert [Center for the Performing Arts] has always been very unique to me, maybe because I have a long history with that center. I’ve performed on every stage — even in the lobby. So I think Krannert feels a little bit like home.

Lindholm: It feels familiar.

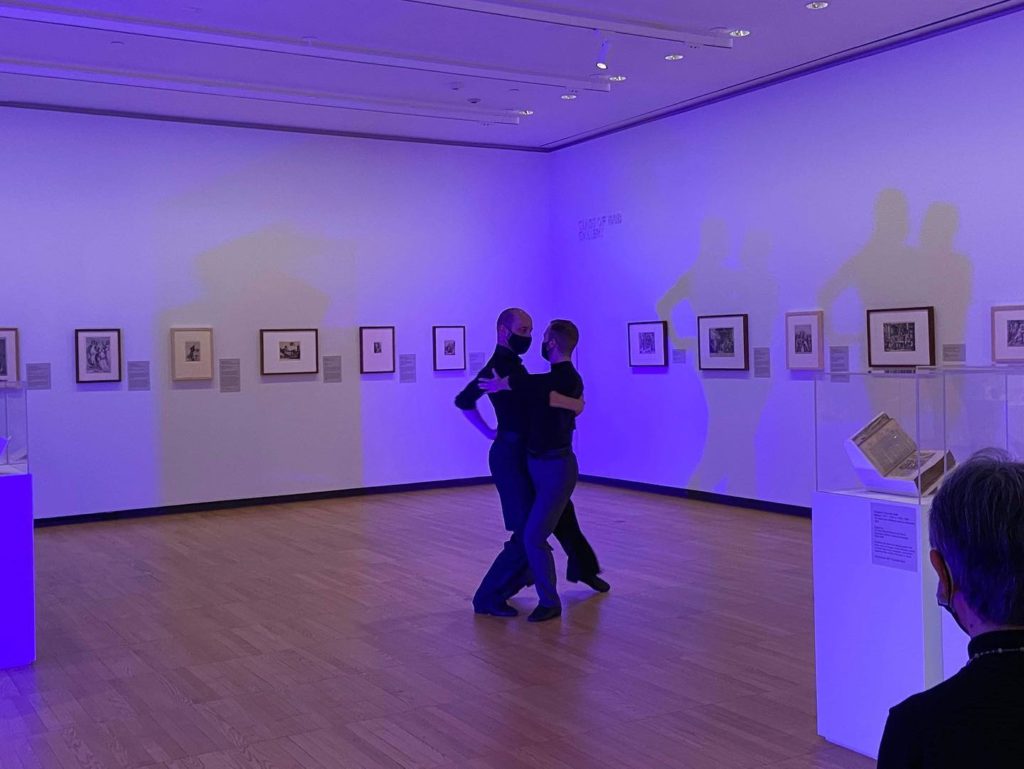

Tecza: It brings back memories. For me, Krannert Art Museum, also actually feels even nicer to dance than an actual stage. As I’m getting older, I’m starting to gravitate towards more non-traditional places to perform. Right now, I feel like getting back into the less grand places seems a little more fun.

Lindholm: It is also interesting to have an audience all around you. Sometimes they are behind you or on the side, so you have to take this into account [choreographically].

SP: Alex, you already have an established career as a professional dancer. What drew you to the MFA program at U of I, and why did you decide to go back to school now?

Tecza: Well, I have a very long relationship with the dance department. I started at the U of I as a dance major, and I later made the switch to microbiology, but I already had those roots in the dance department. Throughout our professional career, we would come up here and do workshops in the dance department. And the former head of the department suggested it would be great to have me here to share my expertise and also to learn something as a grad student. Of course, doing ballroom for so many years I got used to doing things one way, so I thought it would be a good opportunity to learn something new and possibly incorporate it into what I do. I think of myself now as a dance teacher rather than a performer, so thinking that most of my performing career is already behind me, but my teaching career is still very much ahead of me, I’m focusing more on the pedagogical aspects of dance.

SP: Competitive ballroom is not without its problems, but one of the things I personally love most about it is that you can go to a competition and there are six-year-olds competing, and 86-year-olds competing — what do you think it is about ballroom in particular that appeals to such a wide range of ages and people?

Lindholm: I think it’s because you can make it what you want. It can be social. It can be competitive. You can dance to the music you like, so if you like Lady Gaga, you can dance to that. If you are a little older and you like Frank Sinatra, you can dance to that. It is so flexible in the expression it can have, it can fit anyone, really.