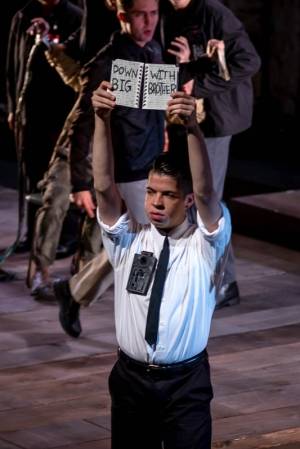

The Illinois Theater at Krannert is kicking off their season exploring freedom of expression with Michael Gene Sullivan’s skillful and deeply disturbing stage adaptation of George Orwell’s dystopian 1984. Though the production is intense, I found that intensity did inspire me to consider serious issues of government control and social responsibility, though maybe not in exactly the way intended.

It’s not hard to see how George Orwell’s classic novel would appeal to a modern theater department. Though some elements of the story may seem retrograde — the ultimately condescending attitude toward women, the occasional overt references to Stalinist Russia — the central concerns of mass surveillance, government propaganda, and state-sponsored torture remain perennially and painfully fresh. The Snowden leaks and the conclusions of the torture report are only the most recent examples of our uneasy relationship with the Department of Homeland Security.

It’s not hard to see how George Orwell’s classic novel would appeal to a modern theater department. Though some elements of the story may seem retrograde — the ultimately condescending attitude toward women, the occasional overt references to Stalinist Russia — the central concerns of mass surveillance, government propaganda, and state-sponsored torture remain perennially and painfully fresh. The Snowden leaks and the conclusions of the torture report are only the most recent examples of our uneasy relationship with the Department of Homeland Security.

However, the presentation of a live production that must, of necessity, portray extended scenes of torture presents a thorny problem to everyone involved. The director must decide how much simulated brutality will provide a sense of seriousness without crossing over into voyeurism or creating an experience so unpleasant that the audience cannot watch it. The actors must discover how to portray the experience of torturing or being tortured without falling into the twin pitfalls of parody or unintelligible frenzy. And the audience must decide how they will negotiate an experience that is almost but not really the same as watching a fellow human be brutalized in front of them.

In this adaptation, Sullivan goes to the heart of this problem and embraces it, establishing the entire piece as a sort of extended form of “enhanced interrogation.” The events of the play, which follow the main points of the book fairly faithfully, take place as a combined forced confession and actual record of Winston Smith’s so-called crimes. On the one hand, this format is an elegant solution to dramatizing a story that is fiercely internal. It allows for an impressionistic and emotional rendition of events that would have been wooden and disjointed without the benefit of Smith’s private hopes and passions. On the other hand, filtering Smith’s life through an experience so horrific that he repeatedly demonstrates his willingness to lie, equivocate, and backtrack adds an interesting note of ambiguity that is less  prevalent in the book. Did Julia exist? Did they really date? Were they really in love? Or is the whole thing simply an elaborate fairy tale constructed by a man driven out of his mind by the horror of a particularly efficient torture chamber?

prevalent in the book. Did Julia exist? Did they really date? Were they really in love? Or is the whole thing simply an elaborate fairy tale constructed by a man driven out of his mind by the horror of a particularly efficient torture chamber?

Smith’s interrogation team plays multiple roles over the course of the production, providing live reenactments of various events he describes. This does help enliven the production, and gives Alexis DawTyne’s cheerfully profane Julia and Ryan Smetana’s deceptively slick “Past” Smith a chance to shine. On the other hand, there are also a few confusing moments where an actor who has been playing an increasingly sympathetic version of someone from Smith’s past will suddenly switch back into an interrogation role the audience has forgotten they have.

It also raises interesting questions regarding the nature of Smith’s predicament. In the book, most of Smith’s torture is at the hands of party member O’Brien, a man Smith respects intellectually and likes personally. When this one incorruptible and unassailable individual promises to wipe Smith out of history, or to force him in a new form, the threat seems real in part because of O’Brien’s solitude. Once O’Brien has established that his loyalty, intellect, and physical power exceed Smith’s, there is no other outside recourse. The story becomes a question of Smith and his internal resources versus O’Brien and his.

Once other people are introduced to the torture chamber, Smith’s set of resources and options become more complex. Should he hope that he has planted a seed of thoughtcrime in one of his young interrogators? Would it matter if he did?

Once other people are introduced to the torture chamber, Smith’s set of resources and options become more complex. Should he hope that he has planted a seed of thoughtcrime in one of his young interrogators? Would it matter if he did?  Could he bribe one of them to help him? (With what? Well, probably nothing. But it does seem odd he doesn’t even try.) And then this line of reasoning again inevitably expands to include the audience. Shouldn’t we be trying to do something for that poor man on the stage?

Could he bribe one of them to help him? (With what? Well, probably nothing. But it does seem odd he doesn’t even try.) And then this line of reasoning again inevitably expands to include the audience. Shouldn’t we be trying to do something for that poor man on the stage?

Here it should be noted that Ford Bowers, who plays the Winston Smith under interrogation, turns in a mesmerizingly committed performance that does a great deal to anchor the second act in particular. His dedication to the physical and emotional demands of a role that involves, among other things, repeatedly simulating a form of electrocution, is technically impressive and harrowing to watch. Though at one point both Smith and the audience are assured that no martyrdom exists in the world of this play, Bowers gleams with self-righteous zeal before being slowly overcome by desperation and anguish.

Here it should be noted that Ford Bowers, who plays the Winston Smith under interrogation, turns in a mesmerizingly committed performance that does a great deal to anchor the second act in particular. His dedication to the physical and emotional demands of a role that involves, among other things, repeatedly simulating a form of electrocution, is technically impressive and harrowing to watch. Though at one point both Smith and the audience are assured that no martyrdom exists in the world of this play, Bowers gleams with self-righteous zeal before being slowly overcome by desperation and anguish.

This performance is well balanced by that of Ninos Baba, who plays Smith’s chief interrogator. His pleasant devotion to the Party’s own special form of interrogation remains unperturbed in the face of Bowers’ impassioned performance, and helps return some of the quality of the book’s battle of wills.

Which brings me back to the question of how to process the play as an audience member. It’s a canard that live theater allows a level of emotional connection between audience and performer that is impossible with film. In this case, whether intentionally or not, that level of connection ultimately begins to feel as though it is implicating the audience in the events on the stage. The second half of the play is particularly intense, and after hearing Smith’s story earlier on, watching his increasingly brutal treatment begins to take a toll. I began to feel a sense of guilt at standing by while (simulated, I had to remind myself, simulated) atrocities were committed onstage.

In the program, director Tom Mitchell speaks of a desire to explore the extinction of individuality in the face of a brutal and oppressive state. For myself, however, the question of collective responsibility in the face of sanctioned brutality seemed at least as poignant. The characters in the play were all subject to varying levels of brainwashing and fanaticism, but as an audience we knew better. In this case, we did nothing because the outrages committed were pretend. But if there was a question in my mind as I left the theater, it was whether I had seen other suffering in other arenas, and remained just as silent.

Though I have made the show sound unrelievedly bleak, there are a handful of much-appreciated and genuinely funny jokes throughout, and many of “Past” Smith and Julia’s scenes are sincere and sweet, in spite of being reenacted by interrogators. The various forms of brutality portrayed on the stage are all bloodless, though there is an uncomfortably realistic waterboarding scene. The notice in the program declaring the production is for mature audiences only is well justified, but for those with the stomach for it, the play is watchable and, perhaps just as importantly, thought-provoking.

———

1984 will run through the end of the month. Times are Thursday through Saturday at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 3 p.m. Tickets are $25 general admission, $24 for senior citizens, $15 for non-U-of-I students, and $10 for U of I students and youth (high school and younger). Flex and series pricing are available.

Photos by Scott Wells.