This weekend saw the return of Ebertfest, the Champaign-Urbana film festival founded by acclaimed film critic and Urbana-native Roger Ebert along with his wife Chaz Ebert. The four-day festival is held annually at the Virginia Theatre, with only one film showing at a time. This format allows Chaz Ebert, and festival attendees, to see all 13 films. This year’s theme, “Empathy at the Movies,” was selected to honor the late Roger Ebert.

Several of our writers and editors attended various screenings this year. While we could not attend every film, our recap hopefully captures some of the magic that is Ebertfest.

— Serenity Stanton Orengo, Arts Editor

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Spoilers ahead! Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari might be more than 100 years old, but it is worth watching for the carefully-crafted twist ending. The premise of this 1920 German Expressionist horror film is simple enough — the eponymous Dr. Caligari hypnotizes the sleepwalker Cesare into committing murders. The film’s events are framed as a story told by a man named Francis, who laments that Cesare killed his friend Alan and drove him apart from his fiancée Jane. As it turns out, Francis is an asylum patient with a tenuous grip on reality, Dr. Caligari is the asylum’s director, and Cesare and Jane are fellow patients. Since Alan is not present at the asylum, it could be inferred that Francis killed him to eliminate a rival for Jane’s affections.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is an early example of a film using an unreliable narrator to set up a twist, and the ending is executed so well that it is easy to appreciate how it became a cliche. The big reveal is foreshadowed from the beginning when an old man (another asylum patient) prompts Francis to tell his story with a non-sequitur about ghosts harassing him. The film’s set design is truly bizarre, featuring crooked angles, painted-on shadows, and surfaces covered in wild, swirling patterns (the asylum sets are comparatively normal). There are multiple close-up shots of blades of grass that resemble knife blades. The sense of unease created by these visual elements takes on new meaning when the plot is revealed to have been a figment of Francis’ imagination.

The strength of this particular screening was bolstered by the live accompaniment courtesy of the Anvil Orchestra (formerly the Alloy Orchestra). In a post-show Q&A, composer/keyboardist Roger Clark Miller and accordionist/ musical saw player/percussionist Terry Donahue described their intention to create a feeling of “tense relaxation.” Their work perfectly underscored the film’s most intense moments without getting too in-your-face, emphasizing instead the theme of empathy at the center of Ebertfest 2023. Ultimately, Francis is not the snarling villain of a slasher flick, but a sick man who needs help. The film ends abruptly after the real Dr. Caligari confidently declares that he can cure Francis, and although the quality of mental healthcare at the time was hardly stellar, it’s a surprisingly optimistic conclusion. (WK)

In & of Itself

I find myself in a conundrum: how do I write a review about a movie I think everyone should see, but not reveal absolutely anything about it whatsoever in said review? In introducing In & of Itself, Chaz Ebert likewise deliberately declined to say anything about the actual film, claiming the audience should know as little as possible going in.

The film is billed as a documentary, a produced recording of Derek DelGaudio’s off-Broadway one-man show that he performed more than 550 times. It’s not really a documentary though, it’s certainly not even a film in a traditional sense — it’s an experience. It’s part autobiographical storytelling, part sleight of hand performance. Yet, the storytelling seeks to reveal truths about the audience, rather than the storyteller, and the magic of the sleight of hand is not diminished even if you can easily spot the “trick.” Not everyone will appreciate it; in the Q&A following the film, DelGuadio revealed that individual executives at both HBO and Showtime passed on producing the filmed version because they didn’t “get it.” The film was only made when Stephen Colbert, who made a surprise appearance via a recording shown before the film, wrote a check alongside his wife to entirely fund the film. Colbert had seen DelGuadio perform live and allegedly sat in the theatre unmoving after it finished so as not to end the experience.

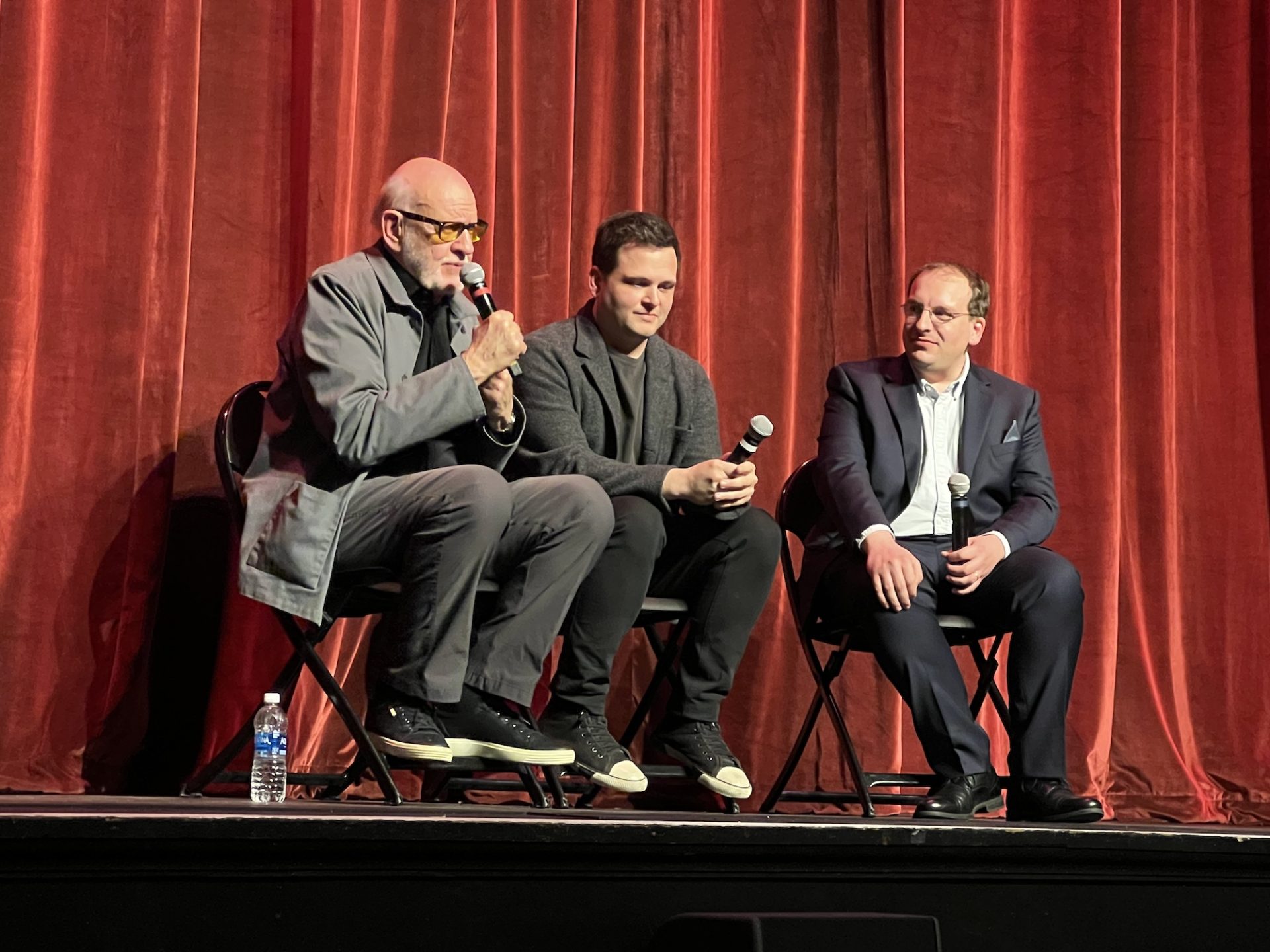

DelGuadio and the legendary Frank Oz, who co-directed both the live and filmed versions, took part in a fascinating and often-times funny panel following the screening (DelGuadio at one point quipped about Oz: “Did you know Frank does a puppet show?”). The Q&A was moderated by rogerebert.com writer Matt Fagerholm, who had seen the show live when it was still being performed and claims he has thought about it daily since. Ebertfest marked the first time DelGuadio and Oz had actually seen the film, originally released in 2020, on a large screen or with an audience of more than twenty people.

DelGuadio and Oz revealed plenty of insightful and funny anecdotes about the creation and original run of the show, including one incident when an audience member and her twin sister hijacked a performance with a six-minute musical number. Yet, they always stopped short of revealing too much. When numerous audience members asked how certain tricks were performed, DelGuadio declined to comment and jokingly called for security. Oz said that while he understands the impulse of wanting the tricks revealed, he wants the audience to “appreciate the wonder.” I’m inclined to agree with Oz with one qualifier: the wonder of this film extends far beyond the capital-M-“Magic,” as DelGaudio calls it; this film defies expectations, and truly you just have to see it. (SSO)

Wings of Desire

“Wow, this is a real old movie theater. Glorious,” said Wim Wenders, his image taking up the screen at the Virginia Theater as he Zoom-ed in for a post-film talk. I, alongside a sizeable audience, had just finished watching his 1987 film Wings of Desire. I’d been wanting to see this film for years, so I jumped at the chance to watch it during Ebertfest. Crisp and beautiful, the film had been recently restored to its intended quality. It centers on two immortal angelic beings, Damiel and Cassiel, as they witness the events of humanity, unable to intervene directly. Through the course of the film, Damiel becomes infatuated with a trapeze artist, and chooses to become human to be with her and experience the richness of human life.

Shot mostly in black and white, the film was one of the last by legendary cinematographer Henri Alekan. Filming this way was a choice meant to highlight the perspective of the angels and their inability to see colors. The choice is evocative, positioning us viewers alongside the angels. This position emphasizes a snapshot of Berlin caught in a specific moment in time, like a softening memory. As Wenders described it, the Berlin seen in this film—with the Wall looming large, dividing the city, its demolished landmarks and lonely denizen—no longer exists. We viewers, like the angels, become timeless witnesses, unable to intervene.

Wenders described for us the process of making the film, somewhat haphazard, where each new day was planned the night before, partially improvised by the actors, with a partly written script. Although chaotic, he described this process as akin to writing a poem, where a new line was written each day. As such, he said the film itself was a poem: rife with symbolism and meaning, the comparison is apt. A few lines of cinematic verse, a stanza in the larger “epic of peace” that the old man Homer fantasizes about in the film.

All in all, it was a wonderful way to spend an afternoon. (AP)

Forrest Gump

It had been a good long while since I’d seen Forrest Gump when I attended the screening at Ebertfest. The film came out in 1994, when I was in high school, and I very much remember the cultural phenomenon that it was. After viewing the film in its entirety through a 2023 lens, as a grown-up person, there are definitely some moments that hit completely differently in today’s world. The fact that the title character is named after and related to Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, who is brushed off as an example of a person making silly choices like wearing bedsheets for clothes, was certainly one of them. The 25th anniversary of the film was just a handful of years ago, and many articles were written examining the conflicting views of the film back in 1994, and in the present. It was in reading these that I learned it was once named the fourth most conservative movie in 25 years by the National Review, which sort of tracks.

Both before and after the screening, Chaz Ebert alluded to the idea that this movie may not fit within our current cultural understandings, discussing that idea with special guest Myketli Williamson, who played the iconic Bubba Blue in the film. Williamson was adamant that Forrest Gump and films in general should be looked at through the lens of the time they were a part of, rather than retroactively through a present-day lens. Williamson spoke quite fondly of his experience making Forrest Gump, particularly about the people that were involved with the film from the actors, to director Robert Zemeckis, to the crew. He casually mentioned that he turned down playing harmonica with Gary Sinese’s band because he was committed to Ebertfest. He had a hand in shaping his character, noting that he almost got himself fired by insisting on wearing a lip piece to give Bubba his signature look, something that Zemeckis was not a fan of. He also did a bit of ad-libbing when it came to the part in the script where he was rattling off the different ways to prepare shrimp. The script called for five or six, and he memorized and recited more than 30 when it came time to film. The character was sort of a blessing and a curse for Williamson, and he spoke about both sides. He took great care in portraying a character with an outward appearance that wasn’t appealing, but that had a pure and kind way of being. The small part made him very recognizable, but only as a character whose lip juts out, even though he’d been in several projects before Gump. He had to hire a publicist to start getting his real appearance circulated in Hollywood. Williamson also briefly mentioned his very low pay for being a part of the film, something he still seemed pretty salty about, understandable given the immense success of the film. Williamson was gracious with his time, especially since the post-film panel didn’t start until around 11 p.m., and answered several questions from the audience. (JM)

This article was written by Will Kanter, Julie McClure, Serenity Stanton Orengo, and Alejandra Pires.