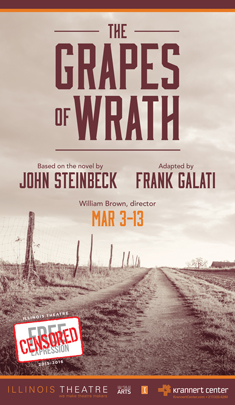

For the next installment in the themed season “Freedom of Speech: Censored”, Illinois Theatre presents The Grapes of Wrath, based on the novel by John Steinbeck, adapted by Frank Galati, and directed by William Brown. Opening tonight, the show will run this weekend and next in the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts.

In the season so far, all of the plays have focused on freedom of expression (or lack thereof), presented boundary-pushing images, and half have been banned in the country where they were written. Not to be outdone, Steinbeck’s novel brings all of the above along with the dubious honor of having inspired bouts of book-burning in America. Despite being an immediate best-seller, and eventually winning the Pulitzer Prize, Grapes of Wrath was burned in the counties of California which felt their citizens were being misrepresented, and the extraordinary censorship of this story has inspired at least one non-fiction book of its own.

In the season so far, all of the plays have focused on freedom of expression (or lack thereof), presented boundary-pushing images, and half have been banned in the country where they were written. Not to be outdone, Steinbeck’s novel brings all of the above along with the dubious honor of having inspired bouts of book-burning in America. Despite being an immediate best-seller, and eventually winning the Pulitzer Prize, Grapes of Wrath was burned in the counties of California which felt their citizens were being misrepresented, and the extraordinary censorship of this story has inspired at least one non-fiction book of its own.

California may have overreacted, but Steinbeck did not portray the Depression-Era El Dorado in a very positive light. Grapes tells the stories of a family of Dustbowl exiles — the Joads, and a few hangers-on — who have followed Route 66 to its end on the barest possibility of a fruit-picking job printed on a flyer. I resisted the urge to use the phrase “bitter end”, because compared to enduring trial after tribulation while on the road, finding a few migrant camps, racism, jail, and eventually work may have actually been a relief. But California wasn’t any kinder than the road to the Joads, or to any of the “Okies” who flooded the state looking for any kind of job.

The parallels to current events both global and domestic are overwhelming. William Brown spoke about asking his actors to do research in the form of clipping out articles about refugee situations or immigrant issues to pin to a board in the rehearsal space. “Eventually we had to stop, because every single day there was a reference to refugees, migrants, how we treat them…or how we don’t treat them. It caused a lot of anger and concern.” Even though the refugees in the Joads’ story are internal, domestic, the resistance from the native Californians is a major theme throughout the work. People in California at the time were sure this influx would collapse the economy, much like resistors claimed when there was a high immigration rate of Vietnamese in the late 70s, and nearly identical to the cries heard about the Mexican population or the danger of Syrian refugees today. Brown went so far to say, “I think there’s even more reason to do the play now than there was when Frank [Galati] did it,” which was back in 1990.

That was a sobering thought, and we reminisced for a moment about the relative calm of that year. It was pre-Gulf War, George Sr. was in the White House quietly inflating the deficit, but because phones weren’t smart and the internet was a zygote, we got our news from one of three network affiliates, and if someone called to tell us – we might have missed the call. All that simplicity set the stage, as it were, to talk about the look and feel of the production. Guess what? Like Steinbeck’s prose and like the view off Rte. 66 between OK and CA, it’s simple. Some of the major set pieces — a truck, a river — Brown says aren’t really there, despite another source’s report that “the creation of the ‘river’ is an amazing piece of scenic craft.” Brown concurs, “…the effect is kind of terrific,” his voice displaying wonder, “I’m pretty amazed at what [the student designers] have managed to do.” The accompaniment has stayed simple, too, with just one guitar played by musician Jordan Pettis. Aside from a few original riffs he plays behind dialogue, all of the music is timely and unembellished: a few Woody Guthrie tunes and some old hymns.

All of that simplicity leaves a lot of room on stage for the emotion, which Brown described as impressive. The cast is made up primarily of upperclassmen and MFAs, who have spent the months since early fall researching the time period and developing their characters. For around 40 players, each has a character name and full history. Many of even the incidental characters did dialect work, because, according to Brown, “You could meet anyone on that road. Everyone was going to California, because that’s where the jobs were. So we have people of color, Mexicans, a Russian lady, a German-Jewish couple, and it’s more than plausible.” The added bonus of having older students, says Brown, “They’ve spent so much time together, it’s like they were almost already a family…the bonding comes with the territory.” Which bodes well for this tale that focuses on family, both by blood and by choice.

All of that simplicity leaves a lot of room on stage for the emotion, which Brown described as impressive. The cast is made up primarily of upperclassmen and MFAs, who have spent the months since early fall researching the time period and developing their characters. For around 40 players, each has a character name and full history. Many of even the incidental characters did dialect work, because, according to Brown, “You could meet anyone on that road. Everyone was going to California, because that’s where the jobs were. So we have people of color, Mexicans, a Russian lady, a German-Jewish couple, and it’s more than plausible.” The added bonus of having older students, says Brown, “They’ve spent so much time together, it’s like they were almost already a family…the bonding comes with the territory.” Which bodes well for this tale that focuses on family, both by blood and by choice.

At the heart of this story is exactly that – a beating heart doing every single thing it can to keep blood pumping to the extremities — in the form of Ma Joad. She’s not the skin, trying to keep everyone together. She’s not the brain, telling anyone what to do. She’s the heart, and although her primary goal is to keep the family alive, it is also full of love. Regardless of the extreme amount of hatred turned towards them, the Joads continually accept and help others, sharing what little they have. Of the actress, Brown observes that she is “an extraordinary actress, certainly willing to bring the strength and the pain.” You may have heard that this play contains a graphic image, nudity, or adult themes. And I’ll confirm it for you without spoiling, but I will tell you that it is engineered by this heart in human form, Ma Joad, doing what is necessary for her family. And while it’s everybody’s choice for themselves whether or not they want to see it, the director and I did share a chuckle about what it would have meant to censor out that particular scene, considering this season’s theme. “Wouldn’t that have been something?”

After a half-hour talk with Brown, I think yes, it is going to be something. His resume is filled with period pieces and classics, so it is a natural choice to have him at the helm of this American period classic. His cast are “well-trained actors,” in his opinion, and he is used to working with professionals. The cultural stage is set to hear this message, and this story is an incredible vehicle by which to deliver it.

If you’re willing to make this journey with the Joads, The Grapes of Wrath will be staged in the Colwell Playhouse this weekend and next. March 3rd through 5th, all performances will be at 7:30 p.m., and there is a “Dessert and Conversation” opportunity prior to Saturday’s show. March 10th through 12th will also have 7:30 p.m. showings, with a matinee on Sunday March 13th, preceded by another “Dessert and Conversation.” Prices begin at $25, with discounts for senior citizens, other students, youth, and as always, UIUC student tickets are just $10. Dessert and Conversation will add another $7, but I imagine there will be quite a bit to talk about.

About Rebecca Knaur…

Editor of Smile Politely’s Arts section, rk makes a habit of drinking mind-altering beverages while writing opinions to be published. She has a highly developed sense of grammar and syntax, but little to no content filter. You can follow her on Twitter, @rknaur, but she rarely checks it, so feel free to reiterate tweets when you see her in person.

Editor of Smile Politely’s Arts section, rk makes a habit of drinking mind-altering beverages while writing opinions to be published. She has a highly developed sense of grammar and syntax, but little to no content filter. You can follow her on

Editor of Smile Politely’s Arts section, rk makes a habit of drinking mind-altering beverages while writing opinions to be published. She has a highly developed sense of grammar and syntax, but little to no content filter. You can follow her on