There’s an old saying that if you go looking for something, you’ll find it. In my case, it wasn’t trouble I was after, it was a through line—a theme or question to shape my Boneyard Arts Festival weekend and my sharing of it with you. While the most pressing question in my mind was “what’s it gonna feel like to explore a festival in this post-but-not-really post-pandemic period?,” that was only the tip of the iceberg. With everything that we’ve gone through these last 18+ months (global pandemic, climate crisis, economic crisis, and racial reckoning), would the work reflect grief, loss, rage, or metamorphosis? Would it inspire catharsis? A glimmer of hope? A path forward?

But before I could tackle those big questions, I had some logistics to figure out. Even with its abbreviated 2021 program, it’s nearly impossible to see all of the festival. So this year, I decided to take a less is more approach. Less stops, more (and richer) experiences. Years ago I’d heard a photography professor explain that curiosity is the key to creativity. And once you find something that excites you, go deep, rather than trying to cover more surface.

So I made a plan. Stay hyper local, which for me meant Urbana, make five stops, and allow for lots of time for exploration. As I considered what the weekend might look like, I found myself inspired by the realization that BYAF would coincide with Juneteenth and the Summer Solstice. My through line just got a lot more interesting.

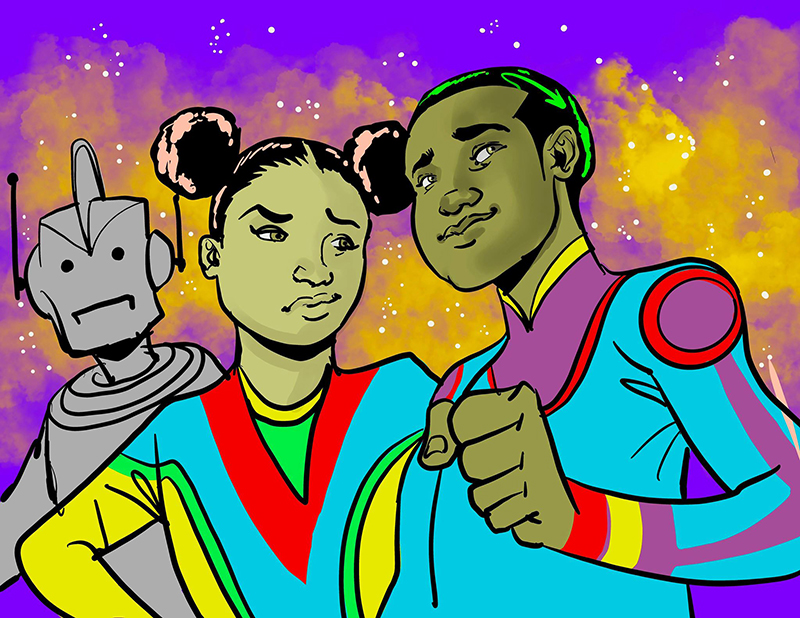

I couldn’t have chosen a better way to start my BYAF experience than by celebrating Juneteenth at STARGAZERS, a poetry and graphic illustration exhibition by Shaya Robinson and Stacey Robinson, displayed at the Urbana Free Library as part of the Artist of the Corridor Exhibition Series.

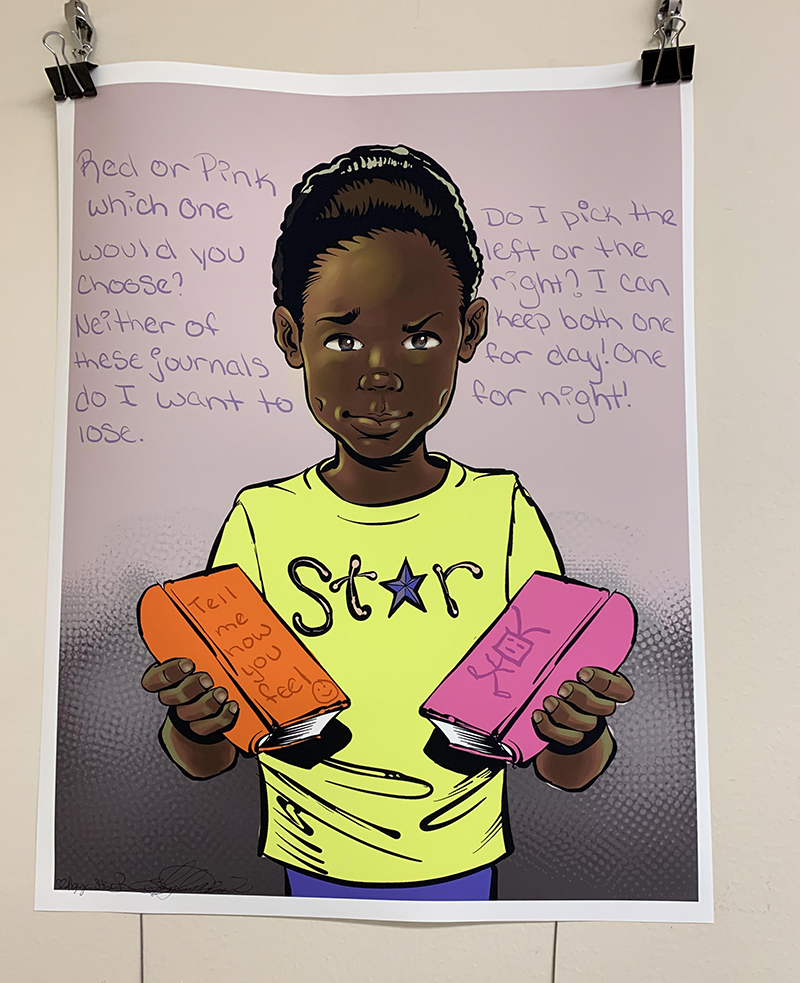

The work tells the story of “how a young girl journals to help her navigate difficult decisions in life. Her journal is a portal to her ancestors who help guide her. Star is a young girl ready to let her imagination along with her spirit guides to lead her through life.”

Stacey Robinson, Stargazer, 2021, digital illustration, © Stacey Robinson. Photo from the Urbana Free Library Facebook page.

I arrived as the artist and poet were setting up for a live art experience with coloring sheets and an iPad. While I had long admired Stacey Robinson’s work, this was my first time meeting him in person. He was as full of energy and as his illustrations.

We spoke about the decision to present a limited but powerful selection of work. It immediately drew you into UFL’s cafe corner and kept you there. I watched as another visitor told him how much the journal illustration resonated with her and reminded her of her own daughter. We talked about the ease of the installation method and how it lent itself to “bringing the work to people,” instead of making them seek it. We bonded over our shared commitment to community-based art and breaking down the town-gown divide. Our conversation reinvigorated me and reminded me of the difference that artists can make.

Stacey Robinson and Shaya Robinson, from Stargazer, 2021, digital illustration, © Stacey Robinson and Shaya Robinson. Photo by Debra Domal.

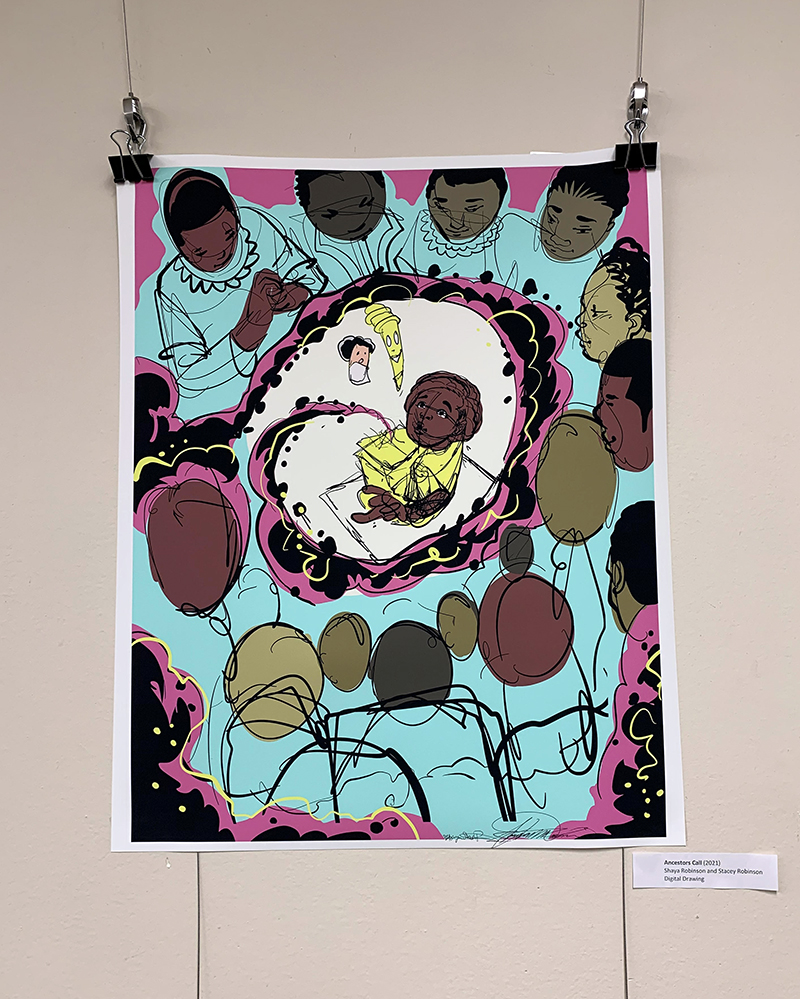

While the entire exhibition was a magical mix its bold colors and line work and powerful thoughts and questions, there was one piece that seemed to be the emotional center. Ancestors Call, shown below, was alive with the power of connection, as the child is fueled by the stories of those who came before her. As I stood before it, watching others respond to its magnetic pull, I knew my Boneyard weekend would be a significant one.

Stacey Robinson, Ancestors Call, 2021, digital illustration, © Stacey Robinson. Photo by Debra Domal.Photo by Debra Domal.

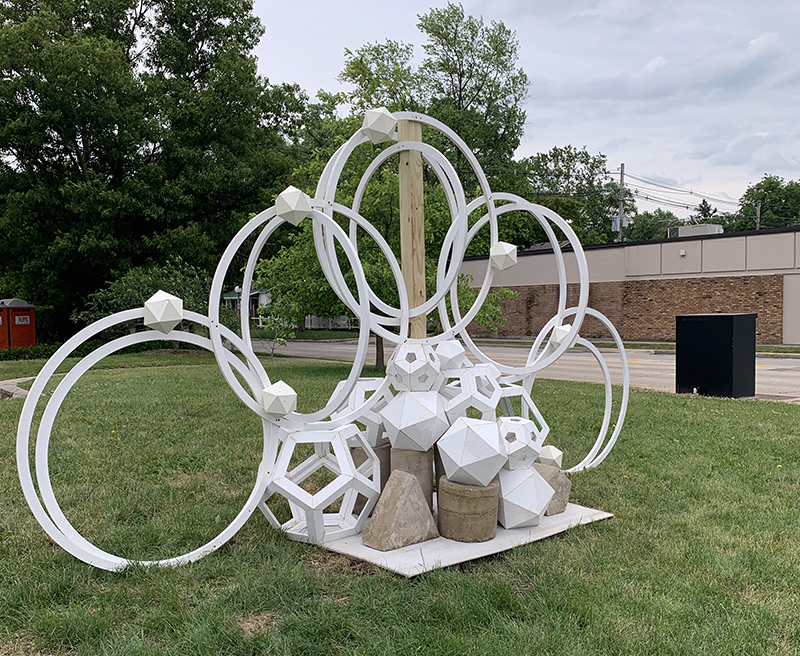

After some time indoors, I was craving some fresh air and headed over to the Urbana City Building to see Nathan Westerman’s Transfiguration II, which was directly sponsored by the City of Urbana Arts and Culture Program.

Nathan Westerman, Transfiguration II, salvaged plywood, latex paint, concrete, fasteners, glue, silicone, 2021 © Nathan Westerman. Photo by Debra Domal.

This lightness of this seemingly simple piece belies the significance of its materials and the depth of its references. Speaking with Westerman I learned the following.

“Transfiguration II is about change: a complete change of form or appearance into a more beautiful or spiritual state. Transfiguration II is constructed of geometric forms made from salvaged plywood painted white and concrete. The lower forms are polyhedrons: dodecahedrons, Icosahedrons. These forms represent Platonic Solids, earth, physical matter. The five rings above the polyhedrons represent God, heavens, the metaphysical. The sculpture references Raphael’s painting The Transfiguration and Bernini’s sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, both examples of points of contact between heaven and earth, spirit and matter. These experience can relate to our modern life through meditation, enlightenment, and higher consciousness.”

Seeing Transfiguration II situated at this location, I began to think about the power of the BLM rallies that had taken place there, and how the impact of so many different voices, here and across the nation, coming together to call for change. As I snapped my photo, I took a breath and hoped the work would inspire the best in all of us, collectively and personally.

From here it was on to explore two Urbana locations from The Great ARTdoors. Talking with Rachel Lauren Storm, Coordinator of the Urbana Arts and Culture Program, I was reminded of the initiative’s evolution.

“The Great ARTdoors came together through the collaborative energies of a team of local arts organizations who joined forces: 40 North, Urbana Arts and Culture Program, Spurlock Museum, Urbana Park District, and Champaign Park District. These kinds of campus-community and twin city collaborations truly grew 10-fold during the pandemic and reflect our own commitment to working and building together. We are so excited to continue and grow this now annual display of local art installations in various parks and neighborhood gardens.”

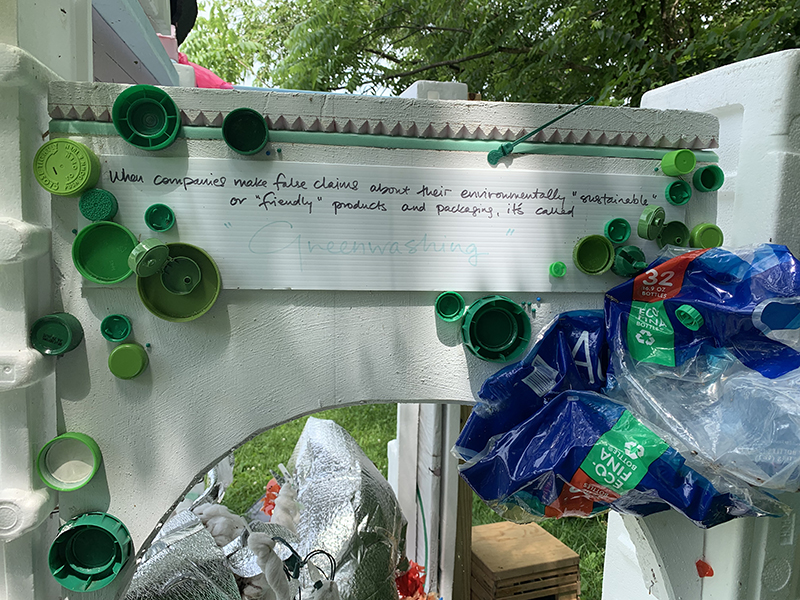

The Summer Solstice, the turning of the seasonal wheel, is a celebration of light. While we often associate it with warmth and lightness, new light can also uncover hidden truths. My first stop was Kim Curtis’ Harvest, at Weaver Park.

Kim Curtis, Harvest, found materials, 2021 © Kim Curtis. Photo by Debra Domal.

I had been inspired to visit Kim Curtis’ Harvest at Weaver Park after Rachel Lauren Storm shared this.

“One of the mantras of this pandemic has also seemed to be “we can’t go back to the way things were” coupled with a call for change or transformation—culturally, socially, in our many ways of being. I also see calls for connection and truth-telling in these pieces. We see that in Kim Curtis’ Harvest in Weaver Park as a call for environmental justice and Keenan Dailey’s Black Love in Skelton Park in Champaign as an ode to Black joy and connection.”

Kim Curtis, Harvest, found materials, 2021 © Kim Curtis. Photo by Debra Domal.

From a distance this work may seem whimsical, but standing before it, inside what is meant to be an urban oasis, its message couldn’t be clearer. As Urbana still reels from the devastation of recent weather (i.e.. climate crisis) related destruction, the shiny holiday decorations don’t seem so festive. To experience this on a solstice is to remember just how much we’ve failed our planet.

Kim Curtis, Harvest, found materials, 2021 © Kim Curtis. Photo by Debra Domal.

Next stop was Greg Stallmeyer’s Melt, at Chief Shemauger Park.

Greg Stallmeyer Melt, welded aluminum painted with automotive urethane, 2021 © Greg Stallmeyer. Photo by Debra Domal.

Ever since my pre-pandemic visit to his studio, I have been fascinated by Stallmeyer’s technique and unique mix of materials. While the full view of Melt captures its power in-situ, I was eager to get a close look at the work’s texture.

Greg Stallmeyer Melt, welded aluminum painted with automotive urethane, 2021 © Greg Stallmeyer. Photo by Debra Domal.

Greg Stallmeyer Melt, welded aluminum painted with automotive urethane, 2021 © Greg Stallmeyer. Photo by Debra Domal.

This dreamy water-like surface is mesmerizing in-person and in natural light. And though you will be tempted by its texture, do not touch the art. As I circled around the work, stepping forward and back to balance the big picture and the fine details, I thought about the title, Melt. Was Stallmeyer expressing a hopefulness for post-pandemic life? A thawing of our fear and separation? Or like Curtis, was he pointing at the dangers of the climate crisis? Perhaps, like my shifting lens focus, the work could contain all of these notions at once.

Storm seemed to echo this in our conversation.

“I think this cycle’s selections of the Great ARTDoors showcase a different type of feeling and visual storytelling than we saw last year. Coming out of the pandemic, there is both hopefulness and grief for what was lost, but also a look towards the future and a sense of relief, a happiness. And that comes through in a lot of the pieces. Charles Wisseman’s Prayer Wheels in Randolph Street Community Garden offers a path through grief and loss in inviting the public to write names and testimonies and poetry on or to deposit in the piece. K Hieronymus W’s Pod No. 7 in Lierman Neighborhood Community Garden turns our quarantine pods into cheery, playful reminders of the ways we connect even when apart. Michael Darin’s Sprout in Citizen’s Park colorfully jets out of the grass as a layered testament to the cycles of experience in life, both bright and dim, but always propelling us onward.”

For my final stop, it was on to the Independent Media Center to see REMOTE WORK, “an exhibition of artworks by Urbana High School AP Art students as part of the City of Urbana’s Artist of the Corridor Program.” Having a number of artists and art teachers in my circle I’ve often thought about the impact of remote learning on art students. How would they fare separated from their studio spaces?

As I suspected, they were determined to create and highly inventive in finding ways to do so from home. The exhibition statement explained it well.

“Ten Urbana High School students spent a year investigating materials, processes, and ideas in AP Art Class. They practiced, experimented, and revised their work to develop their individual artistic voices. This year was particularly unique in that class time was spent critiquing the art students created and all art was created remotely. Every student developed their own studio space. Some turned their bathrooms into film developing stations, some covered their floors with canvases and papers, some created portrait studios in their bedrooms, and others turned the great outdoors into their studio space. These students have demonstrated the resilience and perseverance of true artists.”

From left to right. Owen Vaughan, Sill, digital print from film photograph, 2021, © Owen Vaugh, Jaeden Seaman-Kesler, Projections, digital photograh, 2021 © Jaeden Seaman-Kesler, Alana Brown, Hideaway, digital photograph, 2021 © Alana Brown, Photo by Debra Domal.

REMOTE WORK share billing with works by Freddy West, an artist I’d be curious to learn more about. As a frequently unhoused artist, West relies on non-tradition surfaces, like repurposed board, for his canvas.

Freddy West, Family Portrait (red background), repurposed board (from an old dresser), paint markers and veneer, 2021 © Freddy West. Photo by Debra Domal.

The work expresses a range of Black and African figures and experiences. The eyes of these four women have stories to tell. They express sorrow. They hold you to account with their gazes, both direct and indirect. Their warmth of their vibrant dresses and headscarves stand in contrast to their masked faces; perhaps asking the viewer to question their assumptions when viewing Black and African figures through a white lens.

Freddy West, Coming Home, repurposed board (from an old dresser), paint markers and veneer, 2021 © Freddy West. Photo by Debra Domal.

This last work seemed to sum up my entire Boneyard weekend. A joyful figure caught mid-dance shown in both light and shadow.

As I made my way out of the gallery, I passed through the Queer Clothing Swap. And as I left I found this sign in my path.

Photo by Debra Domal.

I was grateful for the IMC and for Urbana for showing me there was a path forward into healing.