“The Olympics is where heroes are created. The Paralympics is where the heroes come.”

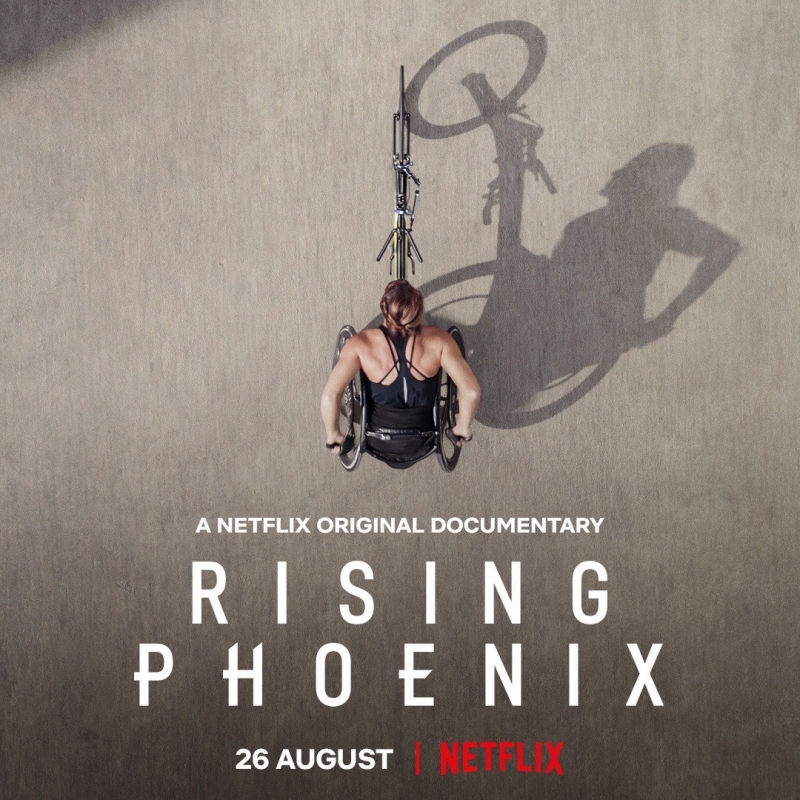

This quote from the former president of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) Xavi Gonzalez introduces Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui’s Netflix original documentary Rising Phoenix, which follows the journeys of several athletes with physical disabilities in the years leading up to the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro. Footage of the athletes in action set to energetic music is interwoven with talking head segments about their lives, the financial setbacks that the event overcame to become the second-most-attended Paralympic Games on record, and how the Games were founded by German-British neurologist Dr. Ludwig Guttman.

University of Illinois alum Tatyana McFadden, who served as an executive producer, is prominently featured detailing how she came to make her Paralympic debut in Athens as the youngest member of Team USA at the age of 15. Rather than presenting these athletes as disadvantaged, Rising Phoenix chooses to focus upon the determination that the Paralympics demands from its participants. As Eva Loeffler, daughter of Dr. Ludwig Guttman, observes, the name “Paralympics” did not come from “paralyzed,” but from how the Games were parallel to the Olympics. Current IPC president Andrew Parsons perfectly captures the spirit of the documentary while discussing how the 2016 Games were almost cancelled due to lack of funding: “Paralympians don’t have the time to worry about what doesn’t work. They just maximize what does.”

University of Illinois alum Tatyana McFadden, who served as an executive producer, is prominently featured detailing how she came to make her Paralympic debut in Athens as the youngest member of Team USA at the age of 15. Rather than presenting these athletes as disadvantaged, Rising Phoenix chooses to focus upon the determination that the Paralympics demands from its participants. As Eva Loeffler, daughter of Dr. Ludwig Guttman, observes, the name “Paralympics” did not come from “paralyzed,” but from how the Games were parallel to the Olympics. Current IPC president Andrew Parsons perfectly captures the spirit of the documentary while discussing how the 2016 Games were almost cancelled due to lack of funding: “Paralympians don’t have the time to worry about what doesn’t work. They just maximize what does.”

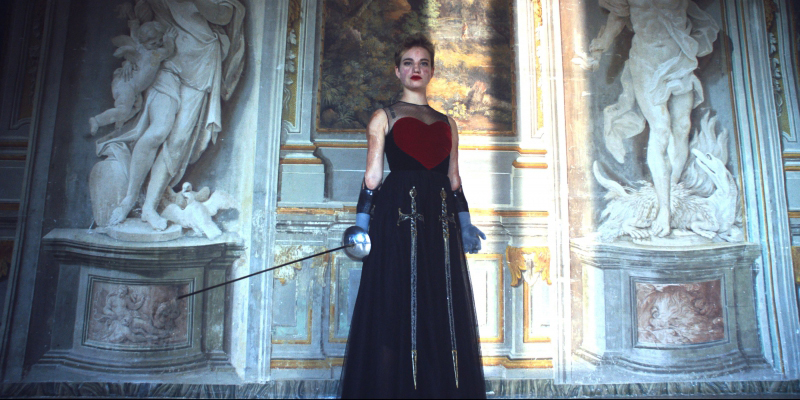

The title, Rising Phoenix, comes from a nickname that Italian wheelchair fencer Bebe Vio had as a child. “Because the phoenix can live and die and burn and live again,” explains Vio. This image fits the documentary’s examination of resilience and willpower nicely, as every athlete interviewed has undergone this metamorphosis in their own way. Vio had been a fencer since she was five and dreamt of competing in the Olympics, but when she was diagnosed with meningitis at 11, her arms and legs were amputated. While adjusting to her new prostheses, Vio went to her old fencing gym and was encouraged to try wheelchair fencing, which she described as experiencing her favorite moment in life twice. “With the disease and all, I completely forgot about (the Olympics). But then, when I went back to fencing, I realized that maybe my dream was not trashed.”

Giving athletes an opportunity like this was what Dr. Ludwig Guttman had in mind when he founded the Paralympic Games, and archival footage has him using language similar to Vio’s: “Paraplegia is not the end of the way. It is the beginning of a new life.” Eva Loeffler tells the story of her family’s escape from Nazi Germany and how Guttman’s treatment of patients with disabilities incorporated athletics, which he proclaimed to be one of his best thoughts as a medical man. The Stoke Mandeville Games, named after the hospital in England where Guttman practiced, were first held in 1948 for 16 former servicemen. The competition grew from there, and the first Paralympic Games were held in Rome in 1960. While talking about the 2012 Games, Loeffler beams with pride at her father’s work. “They weren’t shouting and clapping and cheering because they were seeing disabled people. They were shouting because they were seeing a great sporting event. And that just brought it home to me, what the Paralympics mean.”

Early on in Rising Phoenix, Australian swimmer Ellie Cole notes one major difference between the Olympics and Paralympics is that “in the Olympics, all the bodies look the same. In the Paralympics, none of the bodies look the same.” Home video of Cole learning to walk as a child is shown as she narrates how the discovery of a rare form of cancer on her right leg led to it being amputated when she was three. Cut to Cole in the hospital with her first prosthesis, saying “I want my foot back” with a crestfallen expression on her face. Instead of lingering on this to paint Cole as a pitiable figure, the documentary immediately moves onto her learning to swim and how her interest in ballet influenced her graceful technique. “If I think back to young Ellie, I don’t like to be beaten,” says Cole proudly over footage of her first gold medal win.

Although the documentary does not shy away from the disappointments and frustrations that the athletes have endured, it is not about what they have gone through— it is about where they ended up as a result. French long jumper Jean-Baptiste Alaize speaks to this as he recounts having his right leg cut off and his mother murdered in front of him in the Burundian Civil War when he was three. After quietly stating that he remembers the massacre like it was yesterday, Alaize suggests that running and jumping gives him the means to escape from this memory. As he sprints down the runway and launches himself through the air, Alaize notes in voiceover that “Falling, getting up again. Falling, getting up again, that’s life.”

Despite the dedication and skill of the athletes involved, not everybody wins a gold medal at the Paralympics, which Rising Phoenix emphasizes is nothing to be ashamed of, years of grueling training cannot always be measured by minutes of competition. South African sprinter Ntando Mahlangu, who participated in the 2016 Games when he was 14, observes that “Every athlete is dreaming of the gold medal. But then when I got the silver, it was overwhelming.” Footage of Mahlangu receiving his silver medal has him grinning triumphantly at the accomplishment rather than lamenting how he could have done better. Right before British sprinter Jonnie Peacock is shown winning a gold medal at the 2012 Games in London, he recalls thinking that he would have been happy with a little cheering. “I remember crossing the line and thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve just won.’”

Despite the dedication and skill of the athletes involved, not everybody wins a gold medal at the Paralympics, which Rising Phoenix emphasizes is nothing to be ashamed of, years of grueling training cannot always be measured by minutes of competition. South African sprinter Ntando Mahlangu, who participated in the 2016 Games when he was 14, observes that “Every athlete is dreaming of the gold medal. But then when I got the silver, it was overwhelming.” Footage of Mahlangu receiving his silver medal has him grinning triumphantly at the accomplishment rather than lamenting how he could have done better. Right before British sprinter Jonnie Peacock is shown winning a gold medal at the 2012 Games in London, he recalls thinking that he would have been happy with a little cheering. “I remember crossing the line and thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve just won.’”

The documentary uses these moments as a reminder that it does not matter whether one wins or loses, even if winning is more desirable. Australian wheelchair rugby player Ryley Batt relates the disappointment that he felt after Team USA took home the gold medal at the 2008 Games in Beijing, even though Team Australia won silver. “That silver medal sat on my bedside table. I would look at it every morning, and go, ‘No, that needs to be gold. Get yourself out of bed, and go be an athlete,’” said Batt. He would go on to win gold for Australia in both the 2012 and 2016 Games, which Batt fondly states would have made his late grandfather proud. American archer Matt Stutzman is seen barely missing a winning shot at the 2016 Games, and while he admits in voiceover that it was difficult to recover from the loss, the documentary does not paint any of the athletes as more or less successful based on how many medals they have won. There are no losers at the Paralympic Games.

Rising Phoenix is available for streaming on Netflix.

All photos from Netflix