The first impression as the curtain goes up in the Colwell Playhouse is how glad the dancers are to be back.

If there is a theme that ties all of the four dances of November Dance together, then it’s a longing for connection—something that dancers and choreographers alike have been wrestling with how to communicate in a time where dancers (and everyone else) needed to remain six feet apart. Connections run through the choreography as well. Though there are four different choreographers, each with their own vision and expressive goals, the four dances share some movements and gestures between them. The dancers spend significant time fully on the floor, or reaching up from it. There are few leaps and no lifts—the lighter-than-air feeling that so often accompanies ballet is nowhere to be found. The dancers are physically connected to the stage, rarely leaving it.

The performance opens with Anna Sapozhnikov’s Svad’ba, a work inspired by Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces (1923) and her iconic choreography for the Ballet Russes. As Sapozhnikov describes her own work, “Svad’ba takes a deep look into the traditional Russian family structure within the 21st century.” Seven dancers, all costumed in crimson, dance three movements to music by composer Boris Sichon that uses didgeridoo, jaw harp, duduk, and the human voice. While the instruments come from traditions the world over, Sichon seems to have chosen them for something they have in common: their sounds are difficult to reproduce well electronically. The acoustic nature of the music grounds Sapozhnikov’s choreography, making it visceral and almost ritualistic. The most striking thing about Svad’ba is how closely it resembles a fugue—a complex combination of musical themes and fragments whose many moving parts come together to create a cohesive whole—in movement. With this, the economy of Sapozhnikov’s choreography is a brilliant device. The dancers at various points are all imitating each other, drawing their respective postures from the same initial sequence of movements. The movements themselves become less interesting individually as the dance progresses, and the novelty comes from their interlocking and interactions. As the dancers dance in and out of solos and small groups, the longing for connection is clear.

The second offering, Jakki Kalogridis’s Untitled (Ode to a New Atlantis) was created in collaboration with her fourteen performers. The work was specifically commissioned for the department’s first-year students, who have entered college after a year of lock-down during their senior years of high school. As Kalogridis describes the project, “I set out to choreograph a performance of polyrhythms, and I believe I have done just that.” Polyrhythm sets up the visual relationship between the moving dancers. Material choreographed to be slower and more deliberate feels purposeful; material choreographed to be faster feels lighter, improvised, and spontaneous, though evoking a sense of spontaneity actually requires careful management. Two major gestures seem to inform the choreography throughout: hands and arms sweeping to reach upward, and bodies completely on the floor, as though they are dancing in two-dimensional space.

Photo by Natalie Fiol.

The background—changing colors with a shadow resembling a dancing body moving across it—does not directly interact with the dancers on stage, but becomes clearer as the dance progresses from beginning to end. If there is a metaphor for pandemic connection in Untitled, then it may be in the electronic nature of the media that accompanies the dancers. While there are flute and piano sounds integrated into Miles Hancock’s original score, most of the sounds are completely electronic. Likewise, the accompanying visual elements are abstract and electronically manipulated. It is easy to read connection through the electronics in this number. No one is on Zoom (thankfully), but the feeling of connecting through electronic sounds and visuals is particularly strong.

The third work, Love Part One, was originally the closing number and is the project of Donald Byrd, who is the George A. Miller visiting artist. This is excerpted from the larger work Love, but stands well on its own. An original member of the cast, Vincent Michael Lopez, re-staged the movement with the students to music from Benjamin Britten’s Suite for Cello, Op. 72. Of all the works programmed, this one expresses the most open tension and grief for the connections that were broken or impossible during COVID-19. The dance is a study in the slow burn. It begins with a solo dancer, and then throughout the movements none of the pairs or small groups of dancers touch each other, though their movements give a powerful impression of wanting to. Some move in parallel positions, others in complementary ones, and only embrace at the very end of the final movement.

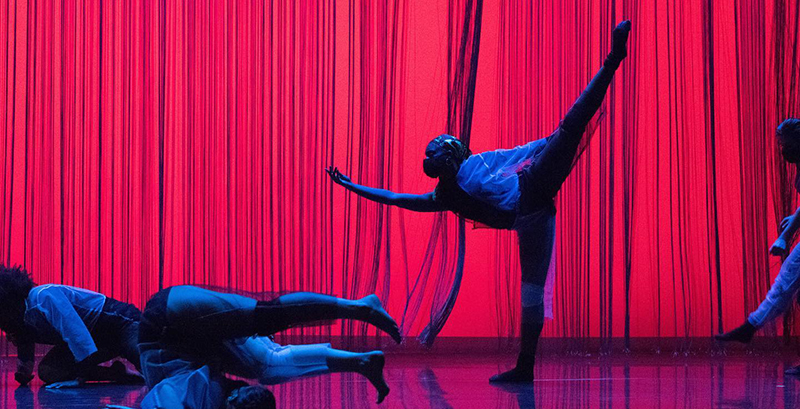

Photo by Natalie Fiol.

The final piece, Jacob Henss’s Harbored Weight, features an original collaborative score for live piano and electronic media. At various moments the dancers also breathe audibly, clap, and manipulate the sounds of their bodies moving through space (e.g., feet against the floor, hands against thighs, etc.). Harbored Weight also has the only instances of dancers interacting with physical parts of the set that aren’t the background screen: a long curtain made of strings that the eight dancers move in and out of at various moments, and a small chandelier that hangs progressively lower throughout the number. By the conclusion, the connection between the dancers has become a release, a setting free.

As Jan Erkert described in her opening remarks, November Dance is ultimately a celebration of audience. With creativity and ingenuity, the University of Illinois dancers and choreographers have been able to find ways to work through the pandemic and bring their work to audiences, largely via digital platforms. The four dances performed for November Dance were clearly made with an in-person audience in mind, to be experienced in a theater (or as closely to it as possible). The last artistic connection—between the dancers and the audience in the space of the theater—is finally restored.

While the in-person performances of November Dance only ran from November 11th through 13th, virtual viewing will be available for free (but do donate if you are able) through November 29th. See below for details.

November Dance

November 11th-November 13th

Krannert Center for the Performing Arts

500 S Goodwin, Urbana

Also available to view live on Zoom

November 15th-29th