As far as operas go, Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw has proven itself adaptable. With a small cast, it proved a good candidate for the Lyric Theater to adapt to COVID production standards, while also creating opportunities to present something more than a conventional staged performance. The Turn of the Screw was filmed live, and is presented in two separate productions (with different casts) via the Lyric Theater @ Illinois Salon portal.

The value and staying power of Henry James’s cerebral ghost-story spookiness, as Virginia Woolf wrote in 1921, is that it “can still make us afraid of the dark.” The plot is, at its core, good suspenseful entertainment. A young governess takes a position at Bly house in the eastern English countryside educating two children and generally overseeing the household, on the conditions that she not leave the children, that she not contact their guardian (her employer) about the children’s and that she never investigate the family’s history. Not at all suspicious. In her widely-circulated criticism, Woolf wrote that, “James’s ghosts have nothing in common with the violent old ghosts—the blood-stained sea captains, the white horses, the headless ladies of dark lanes and windy commons. They have their origin within us. They are present wherever the significant overflows our powers of expressing it; wherever the ordinary appears ringed by the strange.” (Times Literary Supplement, December 22, 1921)

There are so many strange, unanswered questions surrounding the then-ordinary circumstances—a governess teaching children—that an uneasy sense of mystery permeates from the beginning. Why can’t she ask about the family she’s working for? Why can’t she contact him, especially if there is truly a problem? Who else knows about the family and its circumstances? (To name a few.) As it progresses, The Turn of the Screw becomes steadily more unnerving because the scant answers to those questions that do appear only complicate matters further. It also lacks the tropes and resolution of a story like Jane Eyre. No Mr. Rochester appears, as a love interest or as anything else, and there is no wife that he’s keeping in the attic who explains the strange sounds heard after dark. There is unlikely to be a marriage at the end of this, which in opera often signifies resolution. In this, Piper and Britten have given us a thing that rarely occurs in opera: a woman alone with her thoughts, and no love interest or father present to distract her from them.

Myfanwy Piper’s libretto, fashioned after James’s original 1898 story, keeps all of the elements that make the original good, and adapts those necessary to turn a novel into an opera—to take a printed genre and make it a performed one. In the original, which first appeared in installments in Collier’s Weekly, James set the story up as one being told by an acquaintance of the narrator, who reads it out from a handwritten account. There is much fanfare and anticipation leading up to the reading, likely taking up most of the first installment of the serial. Mercifully, Piper and Britten omitted most of this. In the opera, the narrative is still presented as a story being told; in the opening number a male tenor named Prologue sings directly to the audience about a young woman he once knew.

Britten’s score strikes a delicate balance between horror, anxiety, mystery, and pastoral undertones. The orchestra has eleven musicians—five strings, five winds (some with doubled instruments), and a percussionist—and they all have significant parts throughout. Part of the beauty of Britten’s score is its economy. He’s good at creating different effects with a sparse texture, and at creating interest in established material. The music between each scene, for example, is a variation on the theme that opens the opera. In the program available with Lyric Theater @ Illinois Salon access, conductor Michael Tilley offers some excellent in-depth analysis of the themes that Britten wrote and how he used them in the score to aurally mimic the “turning” of the “screw” threads locking together. The wind parts, in particular, pack a lot of expression into small spaces. A sense of the pastoral—of being in the country and in nature, and specifically away from industrial cities—is always present, thanks to the flute, oboe, English horn, and bassoon. Britten doesn’t have to do any more to create this sense than to write for these instruments; musical conventions and associations do the rest of the work for him. Likewise, the sparseness of the texture and the quick changes between established keys, temporary tonal centers, and emotions all contribute to the sense of mystery and anxiety that he is trying to maintain, until it eventually turns into dread and finally, horror.

What is most remarkable about the Lyric Theater’s production of The Turn of the Screw, however, is its technology. Green screen technology does some incredible work for this opera, both practically and narratively. Practically it creates space on the stage—projected images don’t need to worry about following social distancing guidelines. Narratively, it means that the ghosts look more like ghosts and are dramatically more believable, but that the singers are still fully in-character. Director Dawn Harris took a lot of her inspiration for the ghosts from film and television (check out the ShowTalk with Julie and Nathan Gunn for more about her process). In Act I the audience can hear their voices, but only sees them as projected images onstage; in Act II “they break through the abyss and come into our dimension”—their images and voices are integrated.

Another directing choice that Harris made was to maintain ambiguity right the way through the opera. It would be easy to confirm, one way or another, if the apparitions were a fantasy or hallucination, a product of a young mind largely alone in a mysterious place, or if they were real. That would also spoil the mystery. No confirmation arrives. Neither do answers to the many questions that both the young governess and the audience have been steadily acquiring since the opening curtain. In the end, Britten’s opera maintains James’s original mystery, the kind that has listeners exclaiming at its craftsmanship when the lights are on and pulling up the covers when they go out.

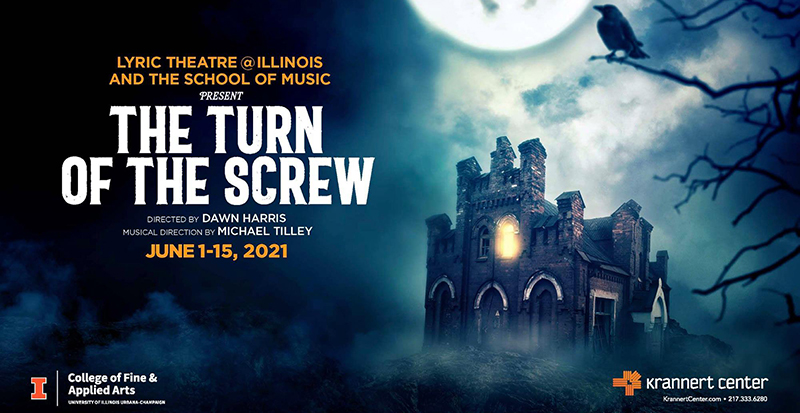

The Turn of the Screw

Presented by the Lyric Theatre at Illinois

June 1st through 15th, online only

Tickets $35/household, $10/student.

Get more information here.