An inside source sent me a hot scoop about a poet who was just published by the prestigious University of Iowa Press, also has his own small press operation, and had recently moved to town. Something about his University Department’s website, which briefly mentioned “scholarly publications,” pinged as “literary journal” to me — probably because we’re so close to Pygmalion LitFest and I’m having trouble getting my hands on the works of some our featured authors. It’s consuming most of my rational mind. So in an entirely self-serving move, I emailed Aaron McCullough and set up an interview, hoping to use my new connection to my own ends and solve two problems at once: publish an interesting local profile and source some journals. Unfortunately, I read the situation all wrong as far as the journals go, but I did have perhaps the most entertaining interview I’ve conducted since starting at Smile Politely last year.

SP: I must admit – the reason it came to my mind to interview you now is because we’re getting ready for Pygmalion Literature Fest, and I thought as the “Scholarly Communications and Publishing Librarian (Head)”, you might be interested or involved somehow? Maybe have a vested interest in all the Lit Mags coming out? (smooth right out the gate – ed.)

McCollough: Oh, yes, I’m definitely interested in all that, and I have my own small press, [Split-Level Texts] that I run. Just wrote a long email to my co-publisher, trying to figure out long-term business plans for that.

McCollough: Oh, yes, I’m definitely interested in all that, and I have my own small press, [Split-Level Texts] that I run. Just wrote a long email to my co-publisher, trying to figure out long-term business plans for that.

SP: So, being a small-press publisher – what made you say, “Hey, that’s the thing. I should do that.”

McCollough: Yeah, that’s the question. I thought that it would be a cool thing to do. I always liked indie music labels, and I always liked the idea of doing it yourself because that enables you to make your own decisions, and I’m real opinionated about what is good. I wanted to publish stuff that I thought was good, and have a fair amount of control. So my friend Karla [Kelsey] and I had come to the conclusion that there needed to be more venues for the kind of work that we liked, and this was a logical way to approach that and make that happen.

SP: You just basically publish work you like? Or do you lean toward any particular style or school of poetry?

McCollough: Well, it’s a little of both probably, certainly. Karla & I both went to school together at Iowa, so we came out with this certain orientation towards the poetry world. One genetic strand that I was part of was Language poetry. Although it didn’t come from there, one of the Language poets, Barrett Watten, went to Iowa, and Jorie Graham was there for years — she had a real interest in it.

Then also something more like “deep image”: it’s a term that Robert Kelly (who’s at Bard) came up with to describe a certain type of American surrealist tradition.

And a heavy influence on craft, although that’s become increasingly common to all MFA programs, because what else are you going to do in an MFA program?

So we have done books that are by dyed-in-the-wool Language poets, and stuff by poets who are more recent: Generation X people who don’t identify as language poets but clearly are influenced by them, and I count myself in that group and Karla would count herself in that group.

SP: Speaking of school, do you find yourself looking for material from your peers, or students, or elsewhere?

McCollough: We tend to strike a balance between publishing someone who is roughly a peer, and someone who is more established. We do two books a year, and we usually do one of each.

I get blind submissions and I think other poets route people to us, and occasionally we go out and pursue writers, especially with the established authors. Often we’ll say, “Hey, this book of yours from the 80s is going out of print, and a lot of people we know would like to have it, and it costs $150 to buy a used copy.” If the poet owns the copyright, we’ll ask them to let us put it back into print.

I’ve always been attracted to recovery projects, when something doesn’t get as much attention as it should have, again, I think of these things through a music lens. I love records that are amazing but for whatever reason didn’t get the audience that they originally should have, like Big Star or Nick Drake. These are things that you listen to now and you think, “How could this not have been massively popular?”

SP: And some of those things, now, are massively popular thanks to reissues.

McCollough: They have become, yes, it’s like a weird story of things getting thwarted for who knows why? Kind of an underdog fantasy.

SP: It seems like most of your answers link back to music in some way. To you, are music and poetry linked? Is that one of the things that moved you this direction?

McCollough: Yeah, they’re definitely linked. It’s really hard for me to draw a bright line between them, because there’s a fair amount of historical evidence that lyric poetry as we know it comes from a song tradition and then got separated out. The Middle Ages, the troubadour poet, are seen as the origins of the lyric poetry and the romantic love tradition that we think of as the birth of Western poetry. In some ways, it’s not that puerile to think of popular music as poetry, but a lot of people — a lot of poets — really chafe at that idea. Like a few years ago, when Bob Dylan was being talked about as a potential candidate for the Nobel Prize in poetry? I remember talking to some people who were adamant about how it would be the worst thing. First of all, I thought, “Why do you care?”

SP: Right, like, “Are you on the list?”

McCollough: (laughing) “Are you competing, head-to-head, against Bob Dylan?”

SP: “Are you shortlisted for the Nobel and Dylan is going to knock you off that list?” It’s possible, I don’t know any of your friends…

McCollough: It was idiotic, insisting on this gap between popular culture over here, and high culture over here. With mass culture and high culture, it’s important to keep them separated sometimes; I think there’s value to Hermeticism. Other times we need to widen the gaze and say, “Actually, Bob Dylan and Kurt Cobain were tapping into something that we should all be paying attention to.” The group does have an intelligence about itself that maybe isolated wizards don’t have access to. It moves in both directions. There’s something that’s the opposite of Hermeticism that has the potential to achieve the same goals. Some kind of big truth for the human race or culture.

Anyway, back to your question, I’ve played music, not very well, for most of my adult life. I do see really important parallels between the constraints that come from playing an instrument, and the constraints that come from working in language. I wrote lyrics before I could even play music, but I always thought of them as lyrics. It’s only later that I started seriously thinking, “Now I’m writing a poem” as opposed to song lyrics.

For me, the big music thing was the Smiths. I fell in love with the Smiths. I’d never heard anything like it before, and I’d never heard that voice before, and I never turned back. Since 1986, they’ve been my favorite band.

SP: (eyeballing Smiths t-shirt) So you can separate the artist from the art?

McCollough: Unfortunately, Morrissey just insists on being such a jackass. I mean, I do still love him, but he’s the creepy uncle, you know.

SP: As the Head Librarian of Scholarly Communication and Publishing, which could and might encompass preservation of the collaborative materials used to create your book, how is it that the University hasn’t acquired it after a year of your tenure?

McCollough: You know, I have asked similar questions inside my own head, but I have not asked them out loud for fear of being seen as too self-serving.

SP: I’m sure it’d be difficult to prioritize stocking the books of every professor, but I’m guessing teaching professors just put their own works on a syllabus somewhere in order to get that done.

I have been trying to get it through the ILL system, but it’s proving elusive. I’d love to hear anything you’d like to share about it, though, in preparation of reading (and possibly reviewing).

McCollough: There’s some things to hang hooks on that we’ve already talked about…

[being a Generation Xer heavily influenced by Language Poetry among other movements, hating loving Ezra Pound, lifelong identification with music, early infatuation with the Smiths that just won’t quit, underdog fantasies and reclamation projects – ed.]

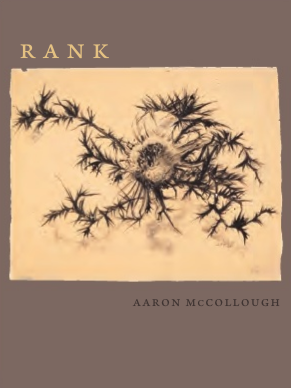

McCollough: The new book is called Rank, and it’s not a pure coincidence that The Smiths’ live album from the late 80s is called Rank, but it’s not like an homage, either. It is and it isn’t. “Rank” is a word that has been in the English vocabulary for quite a long time. It’s a pretty amazing word, it works on multiple levels. It has a particular inflection in contemporary British English that means “foul odor” and “disgusting”, especially in the North. I remember when it came out, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to own it or not; it was a weird sales pitch. And I guess now I’ve done the same thing with my book.

Shakespeare also uses the word a lot, and there’s a lot of wildness – rank meaning overgrown – and all of my work has had some kind of fixation on that kind of American unruliness, disorder, and trying to find order amongst all this. It’s like trying to draw a shape around a scribble, saying, “This is meaningful, even though it’s so chaotic within that shape.”

Also, as I was working on that book, I was beginning to have responsibilities in middle management, which was being somewhere in the hierarchy. The idea of having rank, but there are so many more people who have more rank than you, and thinking of that as a type of spiritual condition.

Those were some of the different associations at play. There’s also a recurring sequence that runs through the book that forces a rhyme between the word “flower” and “guitar”, which is the thematic chorus of the book. It’s designed to pull the reader back to some sort of true north within the context of that world. It’s an overgrown, wild world where things are out of control, but there’s some beauty in it. Which is basically how life is.

It’s very elliptical work, my work in general is very fragmentary, flinty. If it doesn’t feel like that to you, it may have failed, actually.

—

Aaron McCollough’s book Rank is available directly from the University of Iowa Press. Four of his previous books: Underlight, No Grave Can Hold My Body Down, Double Venus, and Welkin are still in print and available for purchase. Little Ease can be purchased used.