Editor’s note: This article is the second in a series about Elective Reportage. Find the first installment, written by Micah McCoy, here.

Elective Reportage was founded in the Spring of 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, based on the idea that society is losing a valuable documentary record of events, people, places, and processes spanning varieties of the significant, but also of the ordinary. For example, in originating this concept, photographer Micah McCoy explained that, with what some may call the “death of print” in terms of the diffusion of electronically based media – and this has occurred in tandem to a transformation of the photographic field towards more freelance work as opposed to contract assignments and commissions – elective reportage is a way to give meaning to the free-flowing, and unrestrained stream of images that appear to be so ubiquitous in contemporary society. McCoy’s idea then, has been to step beyond such forms of documentary by the means that carefully considered photographic practice can provide, while simultaneously embracing these new trends.

Thus, McCoy has constructed a bipartite equation and call for action. The first part is elective, referring to the social impulse to record imagery. It is something that much of society is familiar with, and sometimes loathes. Some may ask, do we need more pictures of cats, of an afternoon salad, of carefully composed self-portraits taken from above to flatter the features of the human face? Such are the well-known tropes and critiques of contemporary photography as a cultural phenomenon, taking the so-called “democratization” of photography (seemingly anyone can take a picture) that commentators like Susan Sontag and Pierre Bourdieu noticed after the second World War to a degree that is as unpredictable as it has been an extension of that earlier period. In this way, there is much historical continuity, and elective refers to the ubiquity of the still image, but also that people choose to take pictures, and furthermore, that they have the right to do so. Indeed, these too are important documents of contemporary times. However, it is in the second part of this equation that McCoy had in mind to interrogate how we choose what images to take. What should we collect? This makes a break, in a modest way, with the ubiquity of the contemporary image.

Reportage, coming from French, means “to carry back.” This does not mean “to return” though, but to bring back factual evidence of some kind which can be exhibited. In general, the photographic tradition is familiar with this term via documentary photography, and especially the humanist documentary photographic tradition. Rather than a written record of events, photographs emerged as a relevant and important means of communication, if not social change, during the 20th century. The medium in this way is meant to evoke a sense of common emotion and unveil universal notions. Photographs were meant to convey a verisimilitude and dexterity of interpretation that words could not, when used in a journalistic style. However, more recent 20th and 21st century commentators on photography have questioned the extent to which any “objective” evidence or universal experience can be obtained from the still photograph. Although, even some critics seem to forget that the powers of manipulation, distortion, and other ethical questions, have always been with this art form, and certainly long before digital processing became available.

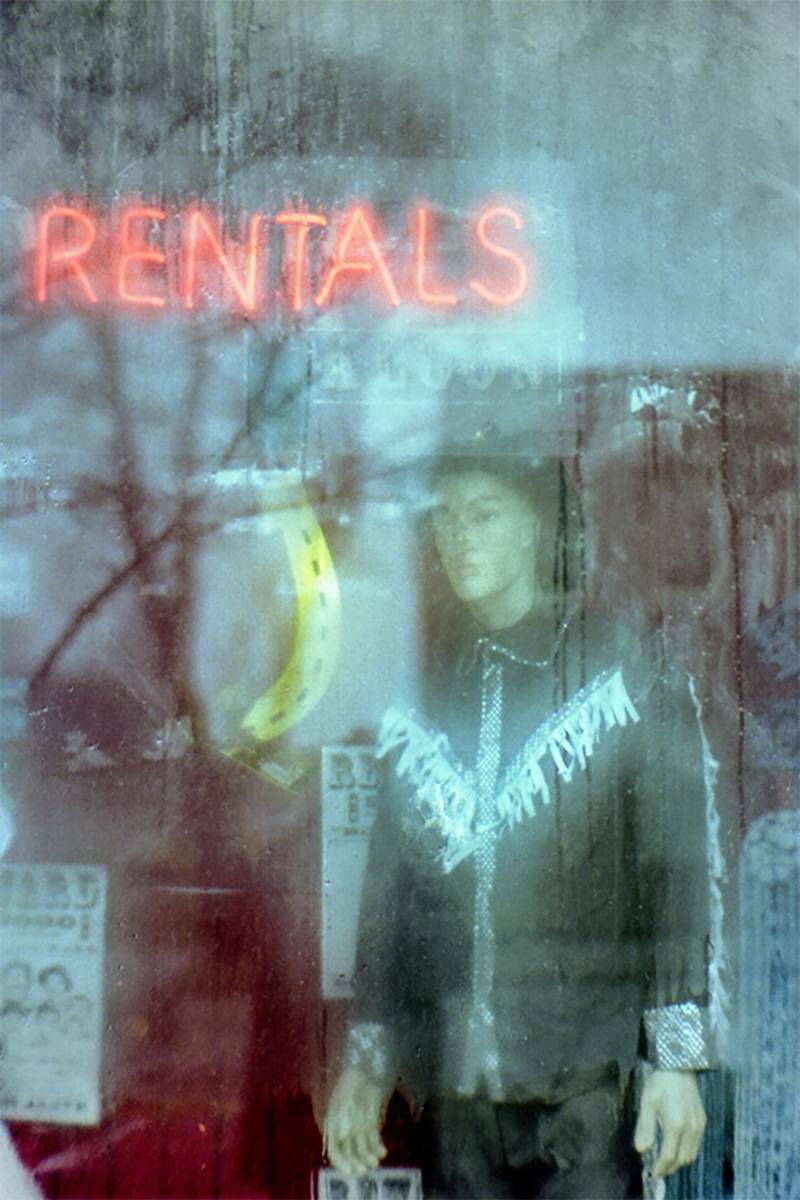

More interesting for the discussion of McCoy’s concept is that when taken together, elective reportage might mean something new and independent of the singular words. When looking to Micah’s photograph of a house just before twilight, one senses an unease. The photographer was trying to interpret the scene that he happened upon, although he did not know exactly what to make of it at the time. The image pays homage to the scene, to a way of life, while recognizing that such moments are quite decisive, in the sense that the passing of old gothic style homes, the street corner mannequins, or the old truck (of course it had to be red), may soon be passed over. And yet, these things linger, and Micah photographs them with a keen interest and fondness, such that they might not be lost.

More interesting for the discussion of McCoy’s concept is that when taken together, elective reportage might mean something new and independent of the singular words. When looking to Micah’s photograph of a house just before twilight, one senses an unease. The photographer was trying to interpret the scene that he happened upon, although he did not know exactly what to make of it at the time. The image pays homage to the scene, to a way of life, while recognizing that such moments are quite decisive, in the sense that the passing of old gothic style homes, the street corner mannequins, or the old truck (of course it had to be red), may soon be passed over. And yet, these things linger, and Micah photographs them with a keen interest and fondness, such that they might not be lost.

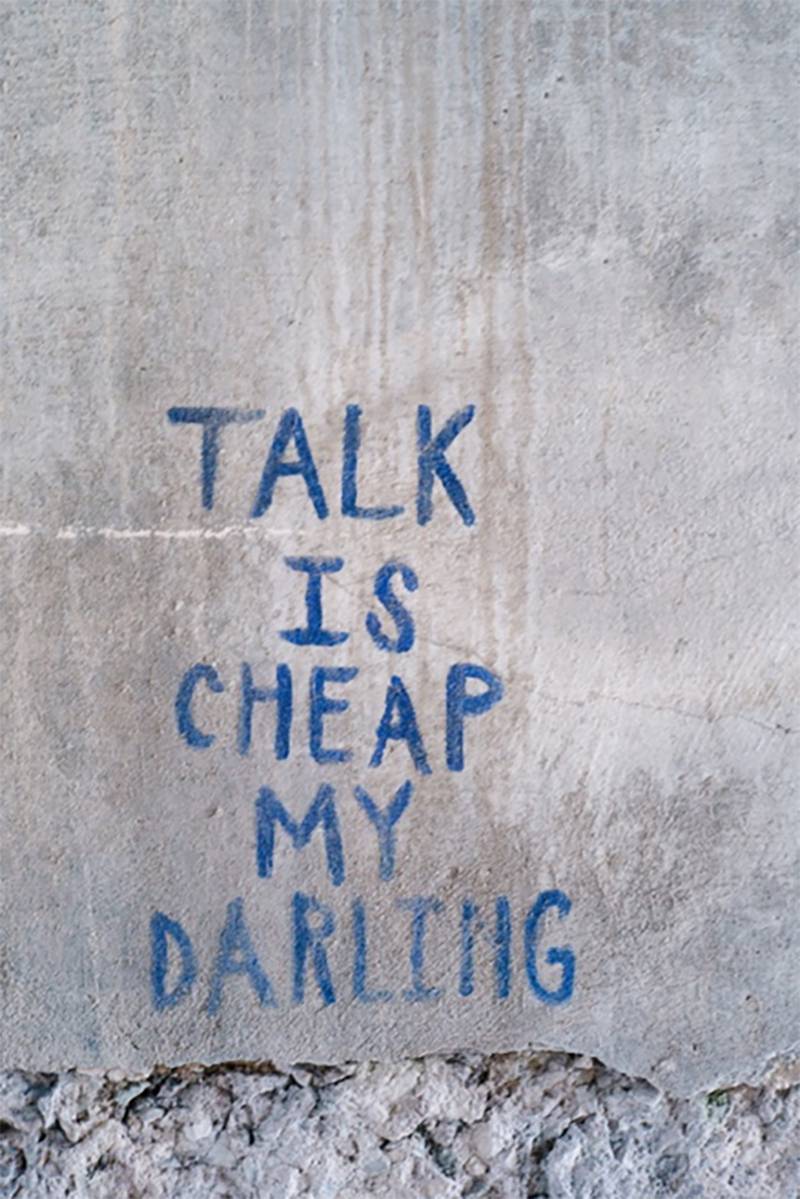

Elective reportage, when considered in this way, is a kind of semi-conscious act. The photographer is choosing to approach the world visually and specifically, that is, photographically. The doorstep is left behind to interpret and encounter the world and the photographer brings back a series of indelible impressions. Although a particular judgment or intentional project is not laid bare beforehand, a project does emerge, forged at the nexus of the external world that the photographer is made to encounter and the pre-situational schemas of perception that one carries. Perhaps one is concerned with the present state of affairs socially and politically, and with the particular character of midwestern American life, and of how certain identities and ways of being seems to exist in tension with an urbanizing world. If there might be a unifying theme among the photography collective of Micah McCoy, Brian O’Neill, Justin Hood, and Nicholas Lusk, this would be it. Perhaps people think of “mid-sized” midwestern cities such as Champaign-Urbana as “sleepy towns” in “flyover country.” However, if these images demonstrate anything, it is to disprove this myth. Increasingly, it is alive with distinctly urban light and color. Author Ray Bradbury, who spent some years of his childhood in Waukegan, Illinois once called the sense of place in his books and short stories, “the undiscovered country,” that place where “it is always turning late in the year. That country where the hills are fog and the rivers are mist; where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and mid-nights stay.” It is this sensibility that brings the works in this exhibition together.

We have arrived then, at a rough preliminary definition of McCoy’s concept. The notion of elective reportage is about posing questions. It is about carrying back images of the urban and peri-urban, and even the rural, as these categories of collective perception morph into something new and unexpected. The photograph then becomes a powerful tool to explore what used to exist in a space, but also what may be. It implores us to carry back with us, and along with us in our lives, those things that we take for granted, or better yet, that which we might not have noticed before.

To conclude, one recalls the famous quotation from the great American photographer Walker Evans, who stated that he was fascinated by photography because what interested him was “what the present would look like as the past.” The photograph records a moment, mediated by the camera, thus creating an experiential separation between the photographer and life as it occurs, and in this moment, it becomes history. Through the photograph and based upon the skill of the photographer to frame and expose the image, a story of reality is retained for the future. Some of these moments are more fleeting than others. The gesture of the passerby may at first appear to be irreplaceable, until one continues walking down the street and finds a neon sign taken down, or a new building being constructed where some-thing used to reside. What was there before? Who lived and worked in these places? The concept of elective reportage thus brings to light the fact that taking photographs, and doing so intentionally, with even the most modest idea of bringing some evidence back of daily life with you, is important. For, even the most mundane and most conspicuous of objects can also be fleeting and decisive.

Elective Reportage would like to thank Analog and Matt Cho for supporting the show and local artists. We would also like to thank our families and friends.

Elective Reportage

Analog

129 N Race St, Urbana

Show up through July

Photos by Micah McCoy