This year marks the 50th anniversary of a significant moment in history, as among other course changing events — the Vietnam War and anti-war protests, the assassination of RFK, for example — the nation mourned the loss of Martin Luther King Jr. Here on the University of Illinois campus, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. precipitated a shift in policy in the form of the Special Educational Opportunities Program, or Project 500. Its basic aim was to increase the number of black and Latino students at the University of Illinois, as well as provide additional supports for the students, including financial aid, a more comprehensive orientation, and continuing advising services. According to the University of Illinois Archives, in 1967 there were only 372 black students out of 30,400. Nathan Stephens, director of the Bruce D. Nesbitt African-American Cultural Center — founded in 1969 as a direct result of Project 500 — says that many of these students were already leading an effort, along with local residents, to push for a more diverse campus: “When Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, the campus leadership agreed that they should do what they could to continue the progress Dr. King dreamt and spoke about. But, the credit goes to the students who initiated and sustained their desires for increasing diversity.”

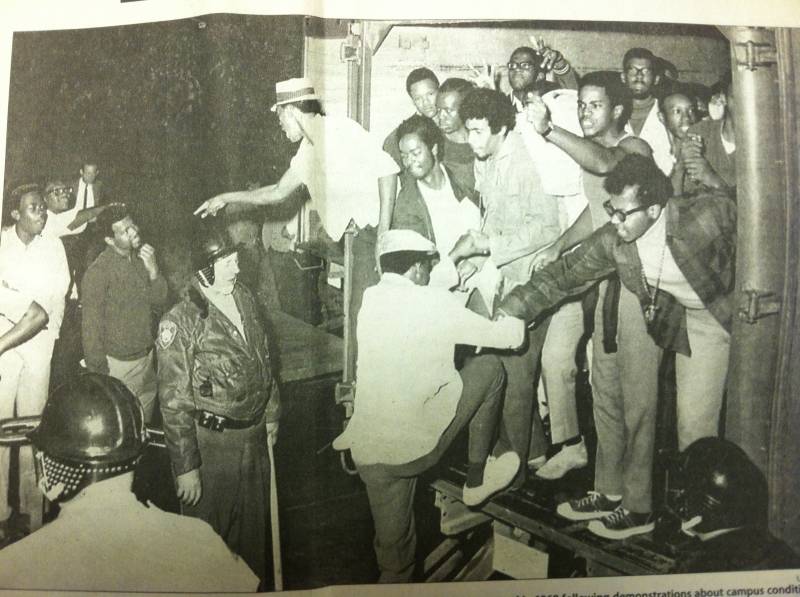

Students are arrested after a protest at the Illini Union. Photo from University of Illinois Archives Project 500 exhibits.

Students are arrested after a protest at the Illini Union. Photo from University of Illinois Archives Project 500 exhibits.

In 1968, 565 additional black and Latino students were admitted to the U of I, but not long after they arrived it was clear that the University was not prepared. Initially housed in the brand new Illinois Street Residence Halls, the students were asked to leave ISR after a week and await more permanent assignments. From a Project 500 online exhibit in the U of I Archives:

Project 500 students were upset when, after a week of orientation, they were asked to leave ISR and wait for permanent room assignments in locations around campus. During orientation, the academic rigor of the school was stressed to the students in the program. SEOP students were concerned they might not be able to meet the high academic requirements when many of their new rooms featured falling plaster and were clearly unsuitable for studying.

Many of the students voiced their concerns through a protest at the Illini Union, and when Chancellor Jack Pelatson did not address those concerns, they damaged some of the furniture at the Union, leading to the arrest of 248 students.

Despite its rocky beginnings, Project 500 has had lasting positive effects at the University of Illinois, and this weekend there will be a celebration of its 50th anniversary including a welcome reception, campus tours, a commemorative concert, a panel discussing the history of Project 500, and a gala, hosted by the U of I Black Alumni Network and University of Illinois Student Affairs. Stephens is the co-chair of the planning committee, and he shared his thoughts about the impact that he sees as a leader on campus today.

Smile Politely: As a leader in the black community at the U of I, and in your work at the Bruce Nesbitt center, how do you see the goals of Project 500 manifesting in campus and student life today?

Nathan Stephens: The Office of Admissions would be best to answer this, but there are scholarship programs such as the President’s Award Program, Illinois Promise, and the Chancellor’s Access Grant that assist with the recruitment of underrepresented students. My center, the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center (BNAACC), participates in a number of additional programs including Future Illini and Start Strong. In addition, BNAACC has a program called the Shelley Ambassadors, named after Dean Clarence Shelley who was hired to assist the Project 500 students during those early days. BNAACC also partners with the Office of Admissions to do some peer recruiting. Finally, there are also programs such as the Peer Recruitment Program, Experience Illinois, Multicultural Academic Achievement Receptions, Next Up Receptions, and the Chillini Visit Day, all of which strive to better a student’s experience on campus.

SP: How is Project 500 and its legacy reflected in the faculty? Can you speak to the importance of students seeing themselves reflected in the faculty?

Stephens: I have had the privilege of meeting a number of faculty who are members of Project 500. Two of my heroes, Dr. Jan Carter-Black is a faculty member in the School of Social Work, and Dean James Anderson is in the College of Education. Dean Anderson was a graduate student during the Project 500 initiation. Both of these individuals are shining examples of what Black students can achieve and the impacts they can make on their community and beyond.

SP: In what ways do you feel the University excels in promoting diversity and inclusion in through its culture, curriculum, and programming? Where can it improve?

Stephens: The University does well with its commitment to diversity related to composition. The campus has students from a variety of races, ethnicities, geographic origins, sexual orientations, gender identities, socioeconomic statuses, etc. Additionally, the cultural centers in the Office of Inclusion and Intercultural Relations (OIIR) allows the U of I to be one of the few schools in the Big Ten Conference to offer such a comprehensive range services and support to underrepresented students. And, many of these units and others across campus offer several programs that promote diversity and inclusion.

The improvement that I would personally like to see on campus is a reflection of the need to improve our country. We are as divided as a nation as we could possibly be. And, what makes this so problematic is that we, as a nation, have immense potential for greatness if we could only band together. Just as the country has not yet lived up to its potential, neither has the Urbana-Champaign campus when it comes to greater diversity and inclusion. We are working on it, we’re just not there yet.

Higher education has historically been, and will continue to be, on the front line and very influential in what America looks like in the next 50 years. We must work to create an expectation of respect and mutual understanding that can become the baseline of values and ethics that will support the development of a campus and communities that promote acceptance, respect, and teamwork despite differences.

SP: What are you most looking forward to doing or celebrating when the new Bruce Nesbitt Center opens?

Stephens: I am looking forward to being centrally located on campus, having adequate space to conduct programs and host events, and to seeing the faces of the black students when they first enter to new center. To me, the new center is the campus’ way of saying, “We did this because we believe in diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

******

There is a wealth of information to be discovered about the history of Project 500 in the University of Illinois archives, and I highly recommend you take the time to take a look. You can go here to find online exhibits detailing the beginnings of the program, and you can listen to oral histories here.

Details about this weekend’s event are available on Facebook.

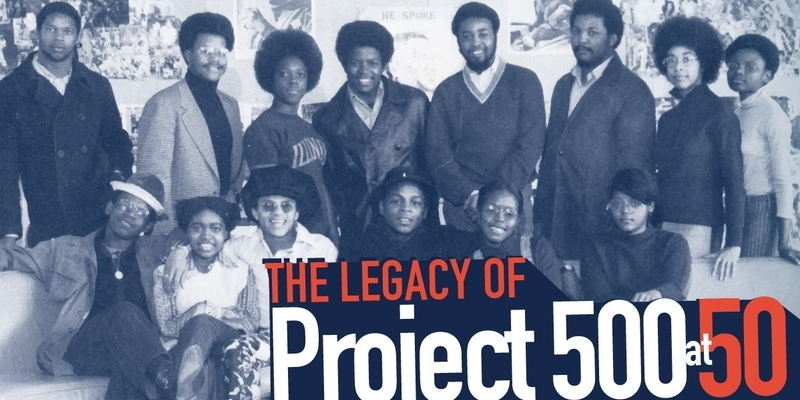

Top photo from the Facebook event