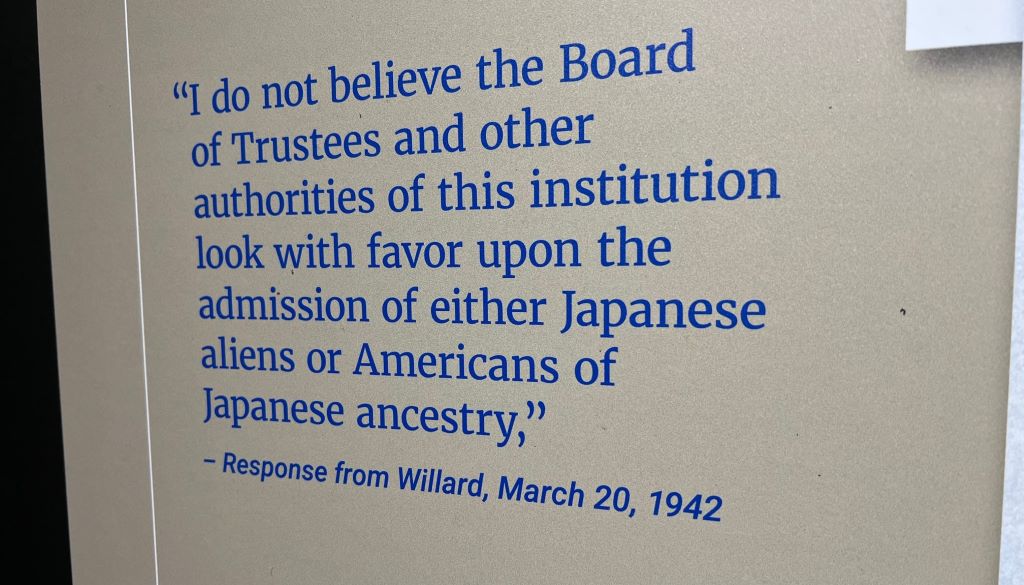

The quote pictured above comes from a piece of correspondence between former U of I president Arthur Willard and the University of Minnesota president. The latter reached out with a question of how to handle current students and faculty, as well as potential new applicants, whose country of origin was a current enemy of the United States.

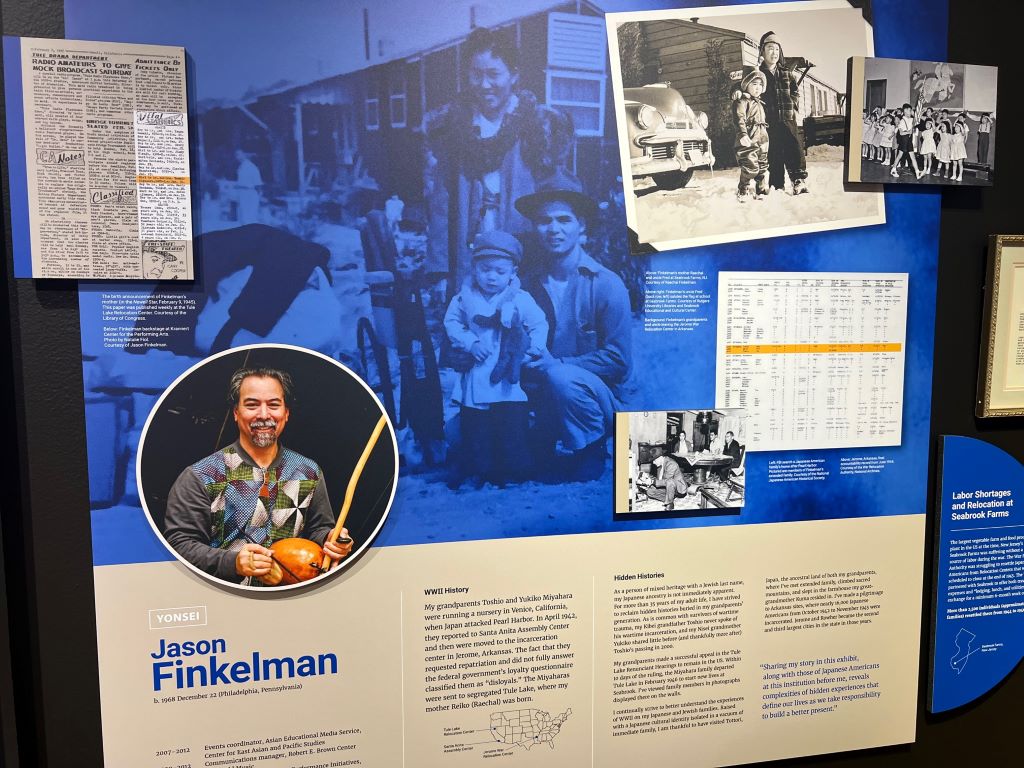

On February 19th, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which “authorized the evacuation of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to relocation centers further inland.” Eighty-one years later, the Nikkeijin Illinois exhibit, curated by Jason Finkelman, opened at Spurlock Museum. The term “nikkeijin” refers to anyone of Japanese heritage living outside of Japan. Finkelman’s exhibit specifically centers Japanese Americans that have a connection to the University of Illinois, either as a student or faculty. Finkelman himself falls into that category. As Artistic Director of Global Arts Performance Initiatives at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, he is also a program administrator for Robert E. Brown Center for World Music, and has collaborated on the AsiaLENS film series with Spurlock, and the Sudden Sound Series with Krannert Art Museum. You may also be familiar with Improviser’s Exchange, where he cultivates a “sonic environment” for students and community members to come together and improvise with instrumentation.

As evidenced above, Japanese Americans in the middle of the country, including at the University of Illinois, were impacted by order. The Nikkeijin exhibit examines that impact through 12 profiles of University of Illinois students and faculty. One of the difficult tasks Finkelman faced was choosing which stories to tell, which might present a broad representation of the Japanese American experience. He used World War II and the subsequent forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans as a touchpoint, sharing experiences of those who were here before the war, during the war, and after. The profiles begin in the early 1900s, and end with Finkelman’s story. “I feel like when you take all of the stories together, you get a complex narrative of the overall experience. Through the commonality of the journey through incarceration, everybody had [their own] journey to endure.”

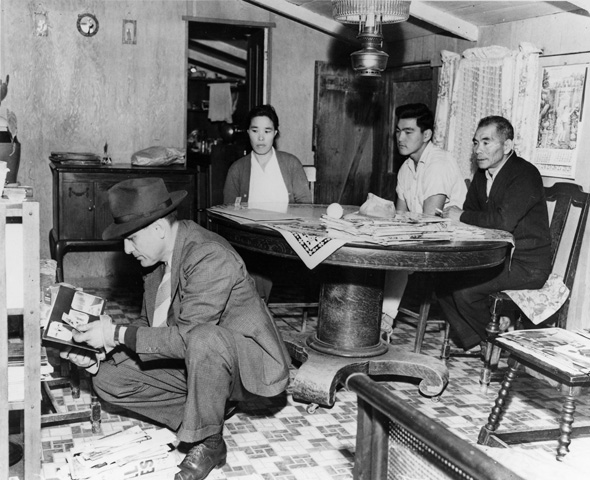

The project is rooted in research Finkelman was already doing on his own family history, something he’s been doing throughout his adult life. “In college when I started doing more reading about the Japanese American experience, I started asking more questions…Little by little I started hearing more of the history of my family. More recently, during this period of COVID, I had the energy and time to really dig deep into my genealogy. I’ve always been fascinated by chasing the photographs and images of family members that are documented and used in books and in films.” In this pursuit, Finkelman discovered that he had a connection to a well-known photograph, featured in the exhibit, of an FBI agent sorting through books as a family looks on from their kitchen table. “Those are extended family members of mine…my great uncle’s in-laws.”

Japanese Americans during World War II faced the impossible decision of declaring loyalty to the United States, or indicating their allegiance, and wish to repatriate, to Japan. Those decisions often led to deep division in Japanese American communities, something Finkelman wants to convey through the exhibit. “There was a divide that happened between those who wanted to prove their loyalty by signing up to fight in World War II as part of the 442 (the U.S. Army regiment comprised of those with Japanese ancestry), and those who were appalled by the fact that they had to answer a loyalty questionnaire…In that generation, that stayed a manifestation through their lives. There are people, and families still today that are divided by those choices.”

His grandfather wished to repatriate to Japan, so his grandparents were sent to Tule Lake Relocation Center, where those “disloyalists” were segregated. Eventually, they went through a trial to rescind that stance, and subsequently chose to go* to Seabrook Farms. Around the same time, the Pacific Citizen, which is the national newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League, published an opinion piece condemning those like Finkelman’s grandfather for daring to remain in the country after refusing to fight for it. It’s a sentiment that led his grandfather, and so many others to remain silent for a long time regarding their experiences during the war. On the flipside, those that did return to Japan were considered “the lowest of the low”. For Japanese Americans during that time, there was no “correct” choice. Says Finkelman, “the only correct choice was having the resolve to get through it.”

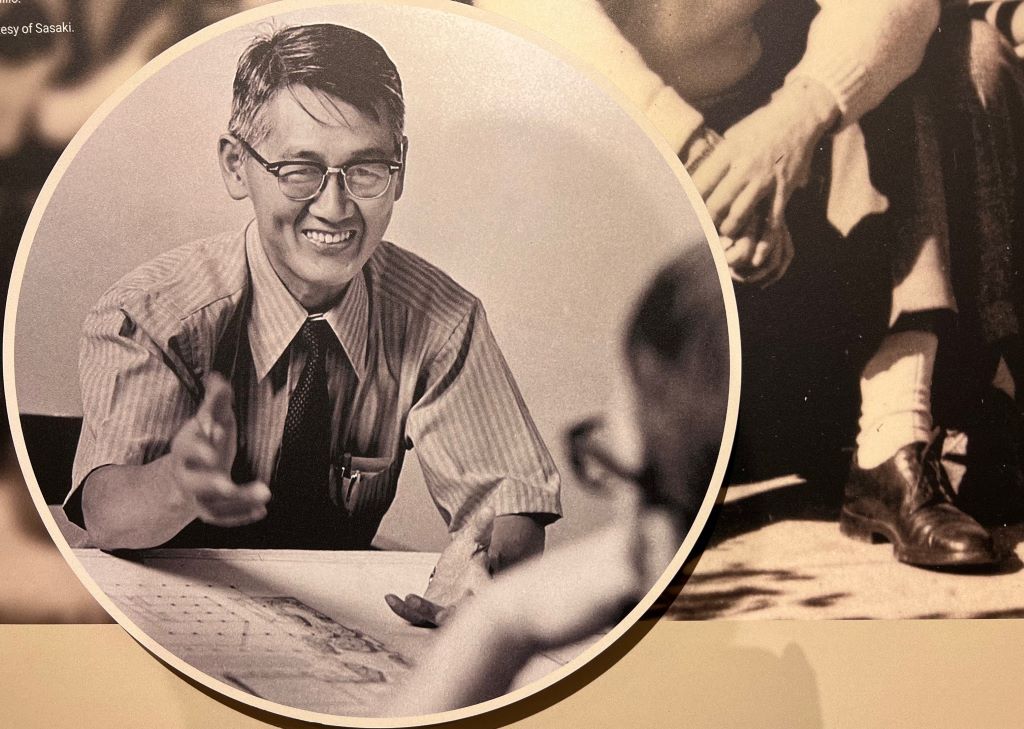

As you follow the exhibit chronologically, you’ll find the stories of people like Hideo Sasaki, a well respected landscape architect who received his BFA from U of I after spending time in an internment camp in Arizona. His landscape design is visible on campus at Krannert Center and the Art and Design building.

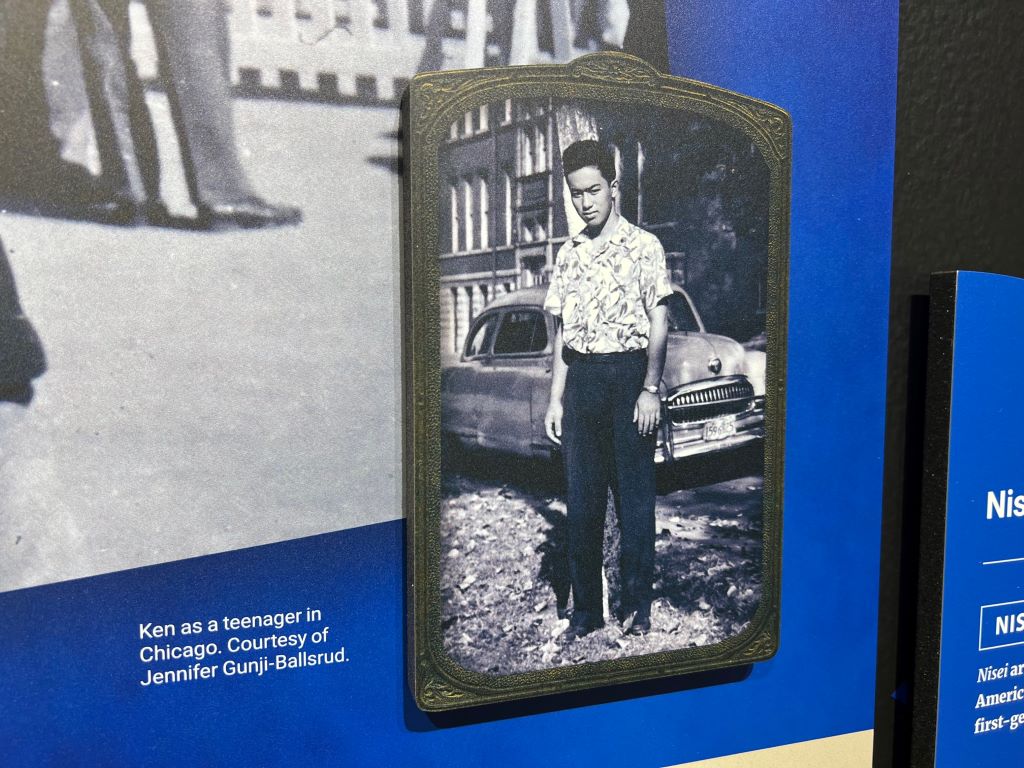

Further down is Ken Gunji, who earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree at U of I, before serving in the army and then returning to work in student services. His wife Kimiko served as director of Japan House, a position now held by his daughter Jennifer Gunji-Ballsrud.

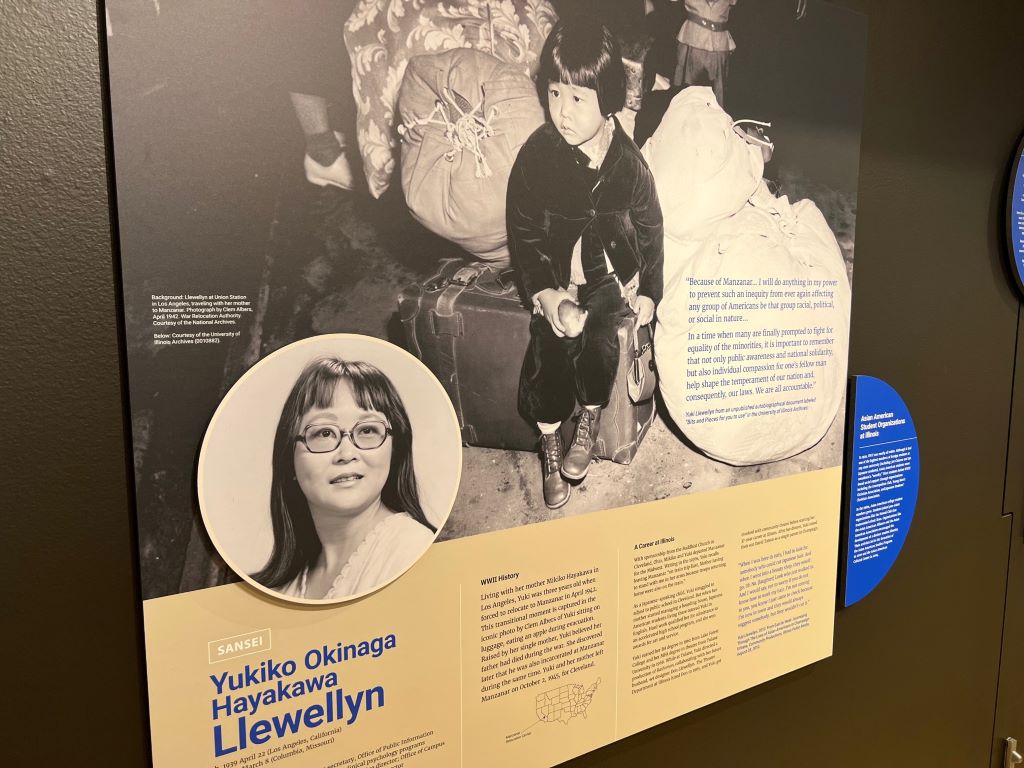

The face of the Nikkeijin exhibit, Yukiko Okinaga Hayakawa Llewellyn, spent her career at the University of Illinois in multiple positions, before becoming Assistant Dean of Students and Director of Registered Student Organizations. The image of her as a toddler, sitting on a suitcase awaiting a train to Manazar Relocation Center, is an iconic symbol of the time of Japanese internment.

The exhibit extends beyond these profiled individuals to showcase other aspects of the Japanese American experience, including racist representations and villainization of Japanese Americans in various forms of media, advertising, propaganda, and more. It’s a jarring display — one to take care in viewing.

Continue on to the Central Gallery to another exhibit, American Peril: Faces of the Enemy, which poignantly accentuates the impact of propaganda on Japanese Americans. It features a series of photographs with Japanese Americans and Muslim Americans posing with pieces of propaganda. The images by photographer Justin L. Chiu are powerful, and worth spending some time with.

Nikkeijin is an important representation of what our country has been capable of in the past. Says Finkelman, “when you understand the historical narrative of the Japanese American experience, and how their civil liberties were denied, and how a whole group of people were forcibly removed from the West Coast, stripped of their jobs, homes, and businesses…understanding that happened, and that there’s still not a definitive legal document that prevents it from happening again.” However just last month, a bill was introduced by Senator Tammy Duckworth that if signed into law would “establish clear legal prohibition against incarcerating Americans based not only on race, religion, and nationality but also sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity or disability.”

Finkelman is hoping to gather more stories for a digital exhibition, to more broadly capture the various experiences of Japanese Americans at the University of Illinois. “I wanted to create a platform to hold all of these stories, because I am curious about how one identifies as being Japanese in the Midwest, at the University of Illinois, in Champaign-Urbana.” There is a form available on the Spurlock Museum website for those interested in being a part of the narrative.

*Editor’s note: A previous version incorrectly stated that Finkelman’s grandparents were “sent” to Seabrook.

Nikkeijin Illinois will be on display through December 10th. Find Spurlock Museum’s hours of operation on their website.