We are all magicians.

“This country practices a particular kind of wizardry…But the most wondrous trick of all is how we treat black girls. We put them in a box and saw them in half. We turn them into villains. And then, right before our eyes, we pull out our magic wand and make black girls vanish into thin air. This is “pushout”.

In recent years, our airwaves and social media have been littered with assaults and daily discriminatory practices wages against the bodies of black people in myriad locations. Most disturbing have been the punitive actions leveled against black girls in American schools, particularly around issues of hair, dress, and discipline. Fortunately, there is a growing body of reporting and scholarship on these issues (follow the links at the end of the article to read more).

As a second generation educator, parent of an African-American daughter, the aunt of African-American college students and a toddler, troop support to a diverse Girl Scout troop locally and cousin, auntie, and frequent participant in playdates and sleepovers of African-American children, I am often reflecting on my own interactions with girls and African-American girls in particular.

So, when I learned that the local Black Teachers Alliance is hosting a screening of the documentary Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls I was elated, but puzzled.

I reached out immediately to learn more exactly what is The Black Teachers Alliance and why they believed a screening of this film was needed for Champaign-Urbana.

Image: A close up shot of Cessily Thomas. She has reddish-brown dreadlocks, black-rimmed glasses, and has large round earrings. She is wearing a black t-shirt and black leather jacket. Photo provided by Thomas.

Cessily Thomas, founder of the Black Teacher Alliance and teacher of Spanish and AVID at Centennial High School in Champaign responded immediately and made herself available for an interview.

We met at Centennial High School in Champaign on a busy Friday morning in the midst of a major construction project at Centennial; the rhythms of the school day punctuated by the droning beeps over the intercom. This interview, in this place in particular, gave me a feel for the challenges of serving approximately 1449 students dodging cement mixers, crane operators, orange cones, muddy sidewalks while teaching, learning, attending meetings, leading student activities, offering collegial support and student advising simultaneously.

Special shoutout to Kendra Bonam, Associate Principal at Centennial, for letting us crash her office for this interview and for fielding student requests and needs so that Mrs. Thomas and I complete our interview.

Smile Politely: Cessily, tell me about telling me about the Black Teachers’ Alliance and why was it established.

Cessily Thomas: A year ago today, I went live on social media about Champaign and whether or not Champaign is a place where black people can live. Is this a place where black people can just be? Is this a place where our kids can just be? At the time, I was the only black female teacher in the school and it was just stressful.

I was having this conversation with someone and they said, “Well, maybe y’all just need a support group?!” So, I was thinking about things that we teachers, teachers aides, hall monitors, and education students could do as a community for ourselves.

I reached out to the Black Teacher Project which is part of the broader National Equity Project, and wondered if we could do something around here.

A friend of mine, Brianna Morgan, and I exchanged ideas and talked about what we can do to try to get all the black educators together in Champaign and Urbana.

We try to meet up once a month to connect, be social, and share resources and strategies in person and via social media. I am hoping that a lot of us will be in attendance for Pushout.

SP: Why is the Black Teacher Alliance needed?

Thomas: You ask, why is Black Teachers Alliance needed? I’ve been teaching here for 10 or 11 years and it’s been rough. When Mrs. Bonam (the African American associate principal in whose office we are sitting) came here, it got a little easier to have someone who can relate to me as a fellow African-American educator. For me, her presence changed my whole experience because she came along at a time when I was looking for another job. How many other black people are the only ones on their job?

****

In reporting this story at Centennial, I wondered about the actual numbers of black educators in Champaign alone. Consistent with Mrs.Thomas’ concerns, the data on teacher diversity is concerning:

According to the District Report Card, the demographic information of the 772 teachers that serve 10,157 students in Unit 4 is as follows:

- 82.2% of the teachers are white; 35.3% of the students are white

- 7.6% of the teachers are black; 35.5% of the students are black

- 4.5% of the teachers are Hispanic; 12.2% of the students are Hispanic

- 5.0% of the teachers are Asian; 8.7% of the students are Asian

- .4% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; .1% of the students are Native American/Pacific Islander

- .3% American Indian; .2% of students are American Indian

These findings parallel national figures that report similar trends. The teaching profession remains predominantly white and female while the students populations are increasingly non-white.

*****

SP: You have talked about isolation as one of few black educators in your building. What other challenges do people mention to you in terms of being a black teacher in Champaign-Urbana?

Thomas: One of the other frustrations is having non-black colleagues minimize your professional experiences or challenges.

Another struggle is doing too much and feeling obligated to advise groups and care for students, especially students of color in this town. Doing too much and overcommitting often happens at my own expense and the expense of my family.

I remember one year there were 4-5 black teachers in this building and there was a real bond between us, and then they were gone. One person went back to her hometown. Another lived in another town, but she decided to work in her hometown. Another one is still in the district, but in a different building.

SP: So the issue of black teachers’ retention is also something the Black Teachers Alliance is also addressing?

Thomas: You can’t take care of black students if you are not taking care of black teachers. So, yes, our work is to recruit and retain black teachers. We are also open to student teachers and education students, even if they haven’t reached the student teaching phase yet. We want them to benefit from having community before they move into the teaching field or the classroom.

From working with students I also have found that there is a direct correlation between how black children experience schools and their desire to be teachers. If black kids aren’t having good experiences in schools, they are not going to ever think about being teachers.

With the Black Teachers’ Alliance, we want to change the way people view the profession of teaching. I want the Black Teachers’ Alliance to be a space where we can get to know each other, support each other, recruit and retain more black teachers, and attract young people to the profession in this community because we really need them here.

SP: How has the district administration responded to Black Teachers’ Alliance?

Thomas: We have had no communication with them or feedback from them, but I have sent invites to all the black teachers to participate in the alliance.

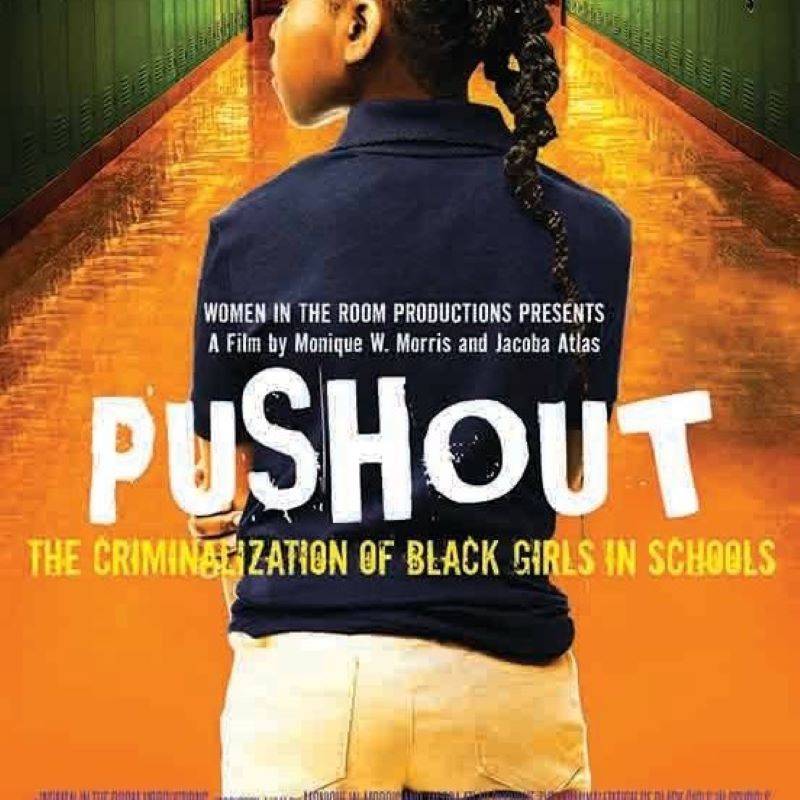

Image: A movie poster that features an artistic rendering of a young black girl facing backwards. She has braids, and is wearing a navy blue shirt and khaki pants. She stands in the center of a hallway lined with lockers. Across the center of the poster is the word Pushout in white block letters. Underneath it says in smaller yellow letters The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. Image from Black Teachers’ Alliance Facebook page.

SP: Tell me about Pushout. Why is it important that Champaign-Urbana see this film?

Thomas: The book changed the way that I really view issues with black girls. When I was reading it, I was really struggling because I have a teenage daughter. My daughter is actually a freshman here at Centennial. When I was reading Pushout, my daughter was in middle school. As a protective parent, I saw the issues one way. But then, as an educator, I found myself thinking about the consequences of constantly policing black girls’ bodies, attitudes, behaviors.

The book was really an eye-opener for looking at my teaching and interactions with black girls differently. I think the danger of teaching is that it is easy to be judgemental about black girls because that impulse to always judge or assess is part of life as a teacher. You can be a good person, but get stuck in that judgemental, harsh perspective. I think that is where I was emotionally in that judgemental, harsh perspective when I read Pushout and the book shook me out of that mindset.

Now people are talking more and more about mental health, but even still, black girls are not given the opportunity to just be, to grow, to make mistakes, to have mental health issues, to struggle with anxiety or to struggle with depression.

Even talking with students in schools, a white male student told me: “If I come in and I’m having a bad day, the teacher will just say, ‘Oh, well, I see you are having a day today!’ But if my friend, a black girl, is having a bad day, the teacher says ‘Oh, she has a bad attitude.'”

These are the kinds of things that kids go through. They tell us these things all the time.

I just think that as educators or people who work with young black girls, we need to step back and examine how we are really seeing them.

SP: Yeah, I just watched the trailer and it was just deeply surprising because it dealt with black girls health and well being and all the concerns that they might bring to school with them. As a parent, daughter of a teacher, and former teacher, the opportunity to step back and examine those relationships and your own behaviors, language and thinking is helpful.

To this end, what is your expectation for the post-screening townhall? You will have parents, fellow educators, administrators, law enforcement, etc. …each with their own point of view and defenses. How do you plan to manage such a diverse conversations?

Thomas: We will have a varied panel made up of professionals in the field as well as students who will share their positive and challenging experiences in Unit 4 schools.

SP: What is the preferred age group for this screening? Some of the content is tough to consume as an adult.

Thomas: I would say middle school, ages 10 and up. But you know, I do believe that upper elementary grade school girls should see this film as well because our upper elementary school girls are having the same issues and experiences in the schools, particularly because our girls experience “adultification” in schools far too often. (According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation study, adultification is defined as “adults viewing black girls as less innocent and more adult-like than white girls of the same age, especially between 5–14 years old”).

*****

Personally, I think the movie is good for the entire family.

If you KNOW a black girl.

If you LOVE a black girl.

If you TEACH a black girl.

If you’ve SEEN a black girl.

If you ARE a black girl,

Then you should see Pushout.

Find more information on the Black Teachers’ Alliance or to reserve seats for the February 10th “Pushout” screening at Centennial on the Facebook event page.

For further reading:

- https://www.huffpost.com/entry/students-strip-searched-new-york_n_5c4d1f70e4b0e1872d4476df

- https://www.theroot.com/residents-of-a-pittsburgh-suburb-call-want-police-fired-1841189263

- https://theglowup.theroot.com/can-kids-be-kids-8-year-old-michigan-girl-banned-from-1838936964

- https://theglowup.theroot.com/those-are-all-little-black-faces-georgia-school-under-1836993787

- https://www.theroot.com/black-girls-most-harshly-disciplined-over-dress-code-vi-1825637134

- https://theglowup.theroot.com/surprising-no-one-georgetown-study-confirms-previous-f-1834802186

- https://theglowup.theroot.com/black-girls-with-braids-reportedly-banned-from-harlem-p-1840576