It is well known that the State of Illinois is hemorrhaging residents. Be it the harsh winters, economic issues, or history of political corruption, many residents are seeking greener pastures in states near and far. To put it in perspective, we recently lost our position as 5th most-populous state to Pennsylvania, almost 90% of Illinois counties have shed residents since 2010, and we in Champaign County are one of only eight counties in the state to not record a population loss. A large portion of this exodus is from the Chicagoland area, but the population loss from largely rural counties like our neighbors remains largely overlooked, despite rural communities contributing the most to population loss since 2010. Although these population losses range only from a few dozen to a few hundred or so per census (conducted every decade), these numbers are significant when a town’s population is under 10,000; for example, Clark County saw a greater proportional population loss from 2000 to 2010 by losing 673 residents than Cook County saw after losing over 180,000 people during the same time period. Of course, counties like Clark are exceedingly small compared to the state’s largest county but it also illustrates how difficult it is for these places to absorb a loss of population, tax base, and/or homeowners and continue functioning as they once did.

The decline of small towns is not unique to Illinois nor is it to places that receive regular snowfall. Naturally, larger urban centers present many job opportunities for those seeking employment but that does not paint the entire picture. NPR reported that rural the employment composition of rural Illinois is 45% more dependent on manufacturing than the United States as a whole. The decline of manufacturing nationally due to automation, and to a lesser extent, outsourcing, has drastically shrunk the job opportunities available in this field, thus reducing the availability of well-paying jobs in many of the less populated areas of Illinois and causing many people to seek a better future in areas with more diversified economies Chicagoland, Champaign-Urbana, or even another state. This is a large reason behind why the 18-34 demographic is projected to have the second-highest rate of exodus from Illinois rural communities. This coincides with the projection that the over 65 years of age demographic will rise in the coming decade, requiring more services and resources from shrinking communities.

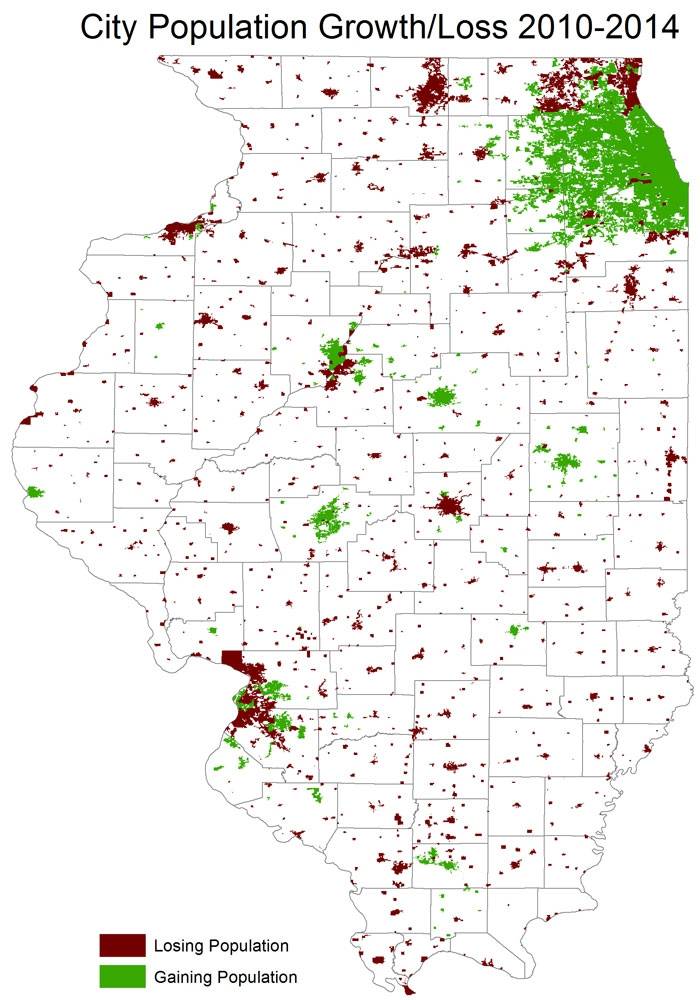

While the major and mid-sized metros of the state show growth, the state’s rural areas are a large contributor of decline (source: Northern Illinois University)

While the major and mid-sized metros of the state show growth, the state’s rural areas are a large contributor of decline (source: Northern Illinois University)

However, rural Illinoisan cities are not taking this trend sitting down. Many cities, especially alongside interstate highways, have looked towards hospitality to provide jobs for their and economic vitality for their community. Construction of shopping centers and hotels on highway frontages are the most visible of these changes, which bank on the geography of Illinois and the multitude of criss-crossing roadways. These ventures do provide construction jobs, but like many new jobs created in Illinois, they are predominantly low-wage. Some places, like Casey, Illinois, have taken a less conventional approach and built a plethora of “world’s largest” objects in order to generate tourism and secure their niche among Illinois towns. But what about the small towns in our area of the state?

Our little section of Illinois, more so than almost any area, is a mixed bag — not great but not as bad as some other regions in the state. Champaign County has continued to grow and many its neighboring counties have been relatively stable in recent years. Douglass and Piatt Counties even tacked on a few residents between 2000 and 2010 in both rural and urban areas. Champaign-Urbana, as the fastest-growing community in downstate Illinois, has led its county’s growth and increased economic activity in communities from Tolono to Rantoul, the latter of which has seemingly recovered from and/or adjusted to the economic blow it suffered when Chanute closed. Even in tiny towns like Ogden, population trends appear to be swinging upward. McLean County, centered around its own pair of twin cities, has been growing at a rate similar to C-U.

Of course, there is decline side to our region. It is difficult to maintain a strong base agricultural jobs in our very small towns in the face of automation. Similarly, the decline of industries such as brickmaking, coal mining, and manufacturing, has left some of our larger cities, like Danville, high and dry as national economic patterns shifted. Our neighboring Vermillion County is predicted to see its fifth straight decade of population loss, and a downward trend is also noticeable in neighboring Edgar and Ford Counties.

Unlike many of the state’s small towns, Champaign County’s towns, like Philo (pictured) have been able to stave off population decline, remain stable, and even grow.

Unlike many of the state’s small towns, Champaign County’s towns, like Philo (pictured) have been able to stave off population decline, remain stable, and even grow.

There is no panacea to solve the complex issue of decline in rural areas. Multiple approaches have been undertaken across the nation to varying degrees of success. One quick solution that many people tout is tax breaks and incentives for business in order to bring warehousing and manufacturing jobs, which can produce jobs in the short term but ultimately do not produce the level of high-paying jobs these industries once did; incentivizing corporations in rural communities is common across the country, yet many rural counties in every region of the US are still seeing population loss. Iowa State’s Agricultural Policy Review has noted that business incubators and connection to high-speed internet (something like our UC2B system) have had positive generally positive effects in attracting business to these communities and they can also improve the quality of life for the residents themselves.

Quincy’s business incubator, QBTC, has been lauded as a success and has been credited for generating sorely-needed growth in the region. Other shrinking communities have rolled out the welcome mat to immigrants by providing support networks and resources, Dayton, Ohio, is an example of such a place that has leveraged its affordability to make it an attractive destination for new arrivals to the country. Since the initiative began, Dayton’s decades-long trend of population loss has slowed and a vibrant and diverse community and economy has begun to take shape. Naturally, there are more resources for an immigrant family in a mid-sized city like Dayton than in a community of, say, 500 people, but many small towns across the country like Seymour, Indiana (population 19,000), have been successful in attracting new residents and experienced a richer culture and stronger economy as a result. Perhaps our region can tear a page from the book of best practices throughout the country and stem the tide of decline in some of our communities.

All of the strategies will cost money and, given the current financial state here in Illinois, investing in our rural communities will be an uphill battle. Many local governments in our area simply don’t have the money to aid in the construction of technology infrastructure or help jumpstart a business incubator. That being said, the state regularly delivers economic development funds to rural towns, so maybe the resources to build the next incubator or broadband cable or hire a translator may be more attainable than we realize. And that’s a good thing, because when a small town fades, so does a piece of Illinois culture.