One hundred fifty-four years ago, Frederick Douglass visited Big Grove Tavern.

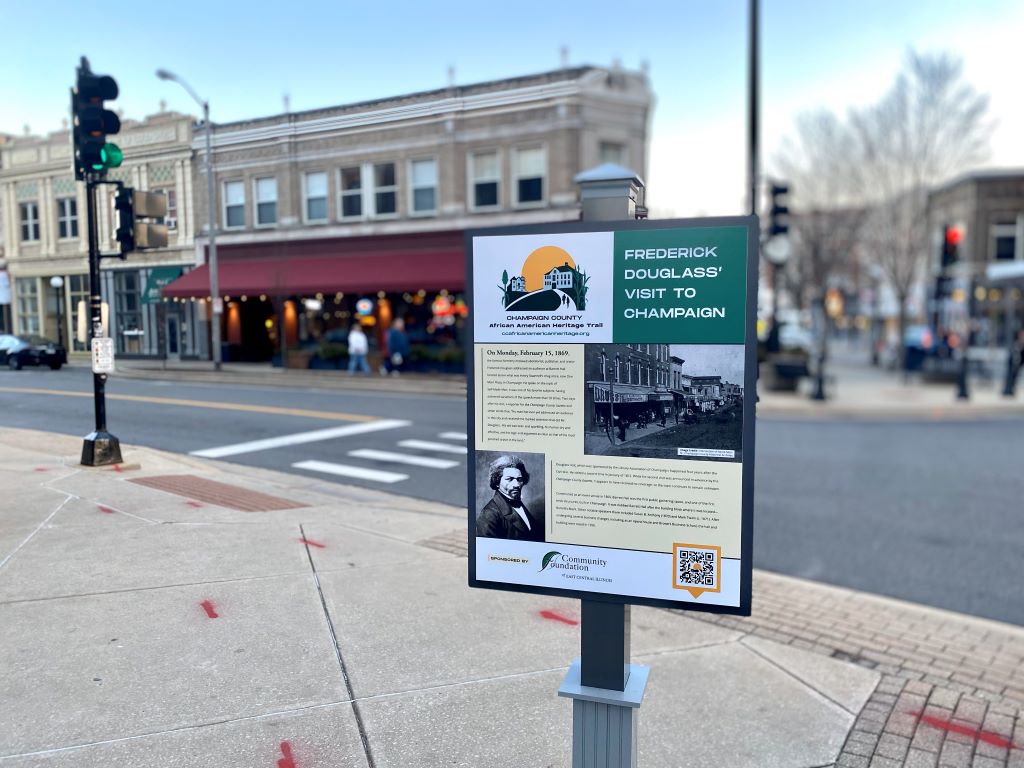

It wasn’t Big Grove Tavern in 1869, though. When Douglass famously orated at the corner of Neil St. and Main St., the City of Champaign was barely a teenager. Now, in 2023, One Main Plaza houses an homage to the historic visit: the first official marker of the Champaign County African American Heritage Trail.

This marker represents the first of 20 physical installations to come. But the wealth of the project lies in its website, where visitors may peruse (and add to) a continuously updated catalog of significant figures, events, and locations. Entries linked to physical sites throughout East Central Illinois — like the St. Luke Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the third-oldest historically African American congregation in Champaign County — populate an interactive map that conveniently flags adjacent locations for easy access.

If inclement weather precludes a self-guided trail tour, worry not. There’s plenty to explore online, including the Points of Pride gallery, which celebrates local art and local artists; an interactive timeline organized by decade from the 1850s to the 1960s; and a roster of upcoming events. Community members can also contribute to the grassroots project by making a donation or buying a brick for the ongoing Skelton Park Transformation.

All told, the heritage trail’s wingspan covers 200 years and most of the county, including Champaign; Urbana; Homer; Rantoul; Broadlands; and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus. Its mission is just as profound: “to educate today’s residents and visitors about the rich cultural history of a people whose stories have been largely unrecognized, but who directly shaped the place we call home.”

I spoke with trail co-chairs Angela M. Rivers and Dr. Barbara Suggs-Mason, who head up a committee of over 30 community stakeholders, to learn more about the trail, its significance, and its role in fostering a culture of empowered storytellers and history-makers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: Thank you for taking the time to talk! Can you begin by sharing a bit about your own personal histories?

Angela M. Rivers: My background is basically art. I’ve been interested in art since I was very small. I earned my BFA from the University of Illinois in painting and worked on two master’s [degrees] there: one in education and one in art history. I have spent close to 40 years working in cultural institutions, including museums in Dallas, Texas; Chicago, Illinois; and here in Champaign. Institutions in Chicago where I have worked include the DuSable Museum of African American History [now the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center], Chicago History Museum, Field Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, and Brookfield Zoo.

Barbara Suggs-Mason: I was born and raised in Champaign, Illinois. I went to Northwestern University for my undergraduate degree in music education. I worked for my cousin’s advertising agency in Chicago [Vince Cullers Advertising, Inc.] which was the first Black advertising agency in the country. I came back to Champaign for graduate school at the University of Illinois and earned a master’s in music education, and ended up teaching music in Oak Park, Illinois.

I always dreamed of replacing Leontyne Price at the Metropolitan Opera, so I followed that dream and studied voice in Europe. I came back to earn a master’s degree in voice performance and literature at the U of I and eventually taught in the suburban districts in Chicago. I ended up as a superintendent of schools in Matteson. I continued to pursue singing, but at a certain age, I thought, “Well, I’m probably not going to be starring at the Met,” so I really focused on education and bringing the world to students.

SP: And the two of you have a unique relationship as well.

Rivers: Barbara and I are cousins through the maternal line. Our mothers are sisters, and her family dates back to coming [to Champaign] in the 1860s, right after the Civil War.

Suggs-Mason: I graduated from Champaign Central High School, as did Angela. My mother’s family came here in the Reconstruction period, my father’s family came here during the Great Migration, and they’re both graduates of Champaign High School. I have a lot of roots in Champaign-Urbana. One of the things that Angela and I have in common is that our grandmothers kept a lot of family history, and we happened to be two of the cousins that were listening.

SP: The two of you share interests in art, education, and history — your own as well as others’. How did those interests help inspire the heritage trail?

Rivers: In 1978, right after I came home from school, I developed and supervised a mural at Park and Fifth Street [“The Pictorial History of African Americans in Champaign County,” informally known as the Park Street Mural] of the history of African Americans here in Champaign County. And then we come to 2020 and George Floyd’s killing, and the response here in the community. The community wanted to do something to celebrate Floyd and to protest, and one of the [Champaign] City Council members remembered my mural and wanted to do something similar. Soon, a committee of like-minded citizens went from wanting one mural to wanting several, and then they thought, “Instead of just doing murals, why don’t we do a heritage trail?’”

Barbara was contacted first, and she asked me if I’d want to work with her. I was already working on our family history and had been doing research on Champaign County, so that’s how it got started.

SP: In 2023, three years after the project was initiated and almost 50 years after the first mural was painted, what about the project are you the most proud of?

Suggs-Mason: The interactive timeline. My hope is that it will be useful for educators. I want this to be something that can be shared with young people so that they can begin to collect their own history, see themselves as historians, and find out stories about their own families that can be shared from generation to generation. That’s how it started for us.

Rivers: The trail sites. Barbara’s strength is education, which is why the timeline became important for her. Coming from a museum background, my strength was of course the history. All the other portions of the website as well as other portions of the project stem from those two initial things. The combination is really what makes this project successful.

SP: Why is this project important right here, right now?

Suggs-Mason: This is a turbulent time in this country, and that’s reflected in the community. For me, knowing my family history and the history of the African American community in Champaign has always been a stabilizing force. Despite whatever microaggressions I might experience, whatever overt prejudice or racism I might experience, I always knew who I was, and they couldn’t take that identity from me. It helped me to persevere through challenging times.

We want our young people to know, as the old folks used to say, “You come from something. You come from somebody. There is pride in the shoulders that you stand on.” More than anything, I hope that we can make this accessible to young people and that they can value their own history. Not just the history on this trail, but their own personal history.

Rivers: Like Barbara said, we come from turbulent times. When I came back to Champaign, I noticed that most people didn’t realize that African Americans had been here in any substantial way before the 1960s. In truth, we have been here for the history of the county itself, starting around 1832.

People don’t realize that we have been in the county as an established community since the founding of its two more important places: the city, and the university. Bethel A.M.E. Church, the first African American-led church here in Champaign County, was established in 1863, the same year that the City of Champaign incorporated itself. Salem Baptist Church, the first Black Baptist Church here, was established in 1867, the same year as the University of Illinois.

It’s like the old saying: “Making a way out of no way.” African Americans have been here, and they made a way and established their own communities, organizations, foundations, churches, and businesses. It’s important that the children understand the importance of that history.

SP: In the process of doing this research, did anything come as a surprise or a shock? Did you learn anything new?

Suggs-Mason: If you sat on our Grandmother Nelson’s front porch on North Fifth Street and listened to her friends talk, you’d have learned an awful lot. One thing I’m happy about is that through this project, a lot of the elders got a chance to do oral histories and talk about their lives and their experiences growing up here. That’s always interesting in that it supports the way we grew up. Because of the University of Illinois, this community is pretty transient. You have people who come and go, and you have a layer of people who never leave. And they don’t really know each other. The trail serves as a communication tool to create less distance between those groups.

SP: The heritage trail takes on multiple forms — the physical sites, the online catalog, and even a wrapped bus for taking the trail on the go. Who are you hoping to reach with these different offerings?

Rivers: When I was growing up, I was told that my knowledge, my awareness of my own history, and my personhood could not be taken away from me. They could strip you of a lot, but they couldn’t strip you of that. It’s taken young people a while to decide that they are interested in history, and I worry that they feel there is nothing there for them, that they have been denied their own history — which isn’t just a feeling but is something that is actually occurring. This project, and projects like this across the country, give the younger generations the information that they need to create their own histories.

We’re trying to look at all different angles that we can present to the public. I think it’s important to emphasize that the mission of this is really to educate the residents and visitors about the rich cultural heritage of African Americans in Champaign County, which has been largely unexplored. There have been occasions when it has, but we wanted to provide something that is sustainable and that can grow in the future.

SP: As students and others learn about and take ownership of their histories, what do you want them to notice?

Suggs-Mason: What I really want people to understand is the joy. Black joy. Black excellence. As a little kid, our families and parents always made sure that we had a lot of joy, even when we didn’t have a lot of money. And that’s what I want people to understand. Despite everything else, despite what we were going through, we had a sense of community, a sense of the village. They aspired, they were people of the uplift, they supported each other. That’s something that I don’t want people to forget. We can’t necessarily replicate that today, but we can understand how people overcame and established themselves in the community in positive ways. I don’t want to make it sound like it was all perfect. It wasn’t. There were issues of school integration, equity of resources, housing issues, job issues. It wasn’t all flowers, but despite all of that we always had a sense of community.

Rivers: And it wasn’t just a sense of community, but it was a community that was controlled and governed itself. Just because someone was a maid, or a janitor, or a cook, someone might think that they don’t have the skills to govern, and that is just not true. Within the Black community, they had to have a sense of government, and people learned those skills through those organizations and through their churches. When it was finally time to elect these individuals to office, they were already skilled in what needed to be done, because they had learned through their interactions within the Black community here.

SP: Is there anything that the trail might help individuals unlearn?

Rivers: There’s a lot of misperceptions about the Black community here, and a lot of misperceptions about Black communities across the United States during that same time period. Champaign-Urbana and the community here is a microcosm of what was occurring during those specific time periods in the United States, and that’s very important for people to understand. It isn’t just something that happened or occurred here, or even something unique. It’s just part of the overall whole. By looking at the microcosm of Champaign County, you can begin to see and understand the overall history of the country. African Americans aren’t separate in the history of the United States. We are an integral part of it. And being able to tell our story here is to reaffirm that.

SP: What is the most important thing you would like people to take away after experiencing the trail?

Suggs-Mason: The expertise of the community. African American men and women wore many hats. Sometimes, they were invisible to the greater white community, but where they lived — where they interacted with each other — they were not invisible. And I hope that we are making our ancestors visible to the community through this project.

Rivers: There’s one of the old sayings, an old proverb. We use a part of it when we say, ‘speak their names.’ When we speak the names of the deceased, it is calling upon the ancestors and making sure that they live forever. And that’s what we’re trying to do, is to ensure that history is maintained for many generations to come.