From country to the blues to varied sounds in between, the music of Lucinda Williams spans generations and genres. The sound of her songs, many of which have an atmospheric tinge to them, has been influenced by musicians worldwide. Her work has been covered by artists such as Mary Chapin Carpenter, Emmylou Harris, and Tom Petty.

On Saturday, April 9, Williams and her band will perform at the Virginia Theatre in Champaign, starting at 7:30 p.m. Fans can expect to hear a wide range of her compositions encompassing sorrow, joy, and, in a change of songwriting direction for Williams, topical subjects centering on politics and relevant issues of the day. Tickets are still available on the Virginia Theatre’s website.

Williams, who has released fourteen albums and won three Grammy Awards, talked with Smile Politely over the phone about what inspires her to write music. She also discussed how independent record labels in the 1990s improved things for artists, and how the stroke she suffered in 2020 forced her to learn how to walk again.

Smile Politely: With such a large catalog of songs, how do you select what you play live?

Lucinda Williams: I try to spread it out and do as many songs from as many different albums as I can. I try to fit in enough different stuff so there’s something for everybody. There are certain ones that I know people want to hear all the time, like “Drunken Angel.” Then we have certain ones we always pull out at the end that are upbeat and up tempo like “Get Right with God” and “Joy” and “Changed the Locks.” People need some good-time-feeling music these days.

SP: Why do you say that?

Williams: Take your pick. It’s either the COVID thing or the political stuff. Bad news everywhere. There seems to be something all the time.

SP: Yeah. Like the war in Ukraine right now.

Williams: Yeah. That’s just a senseless tragedy. I said something about it the other day at a show. I did my song “Man Without a Soul” and dedicated it to Putin.

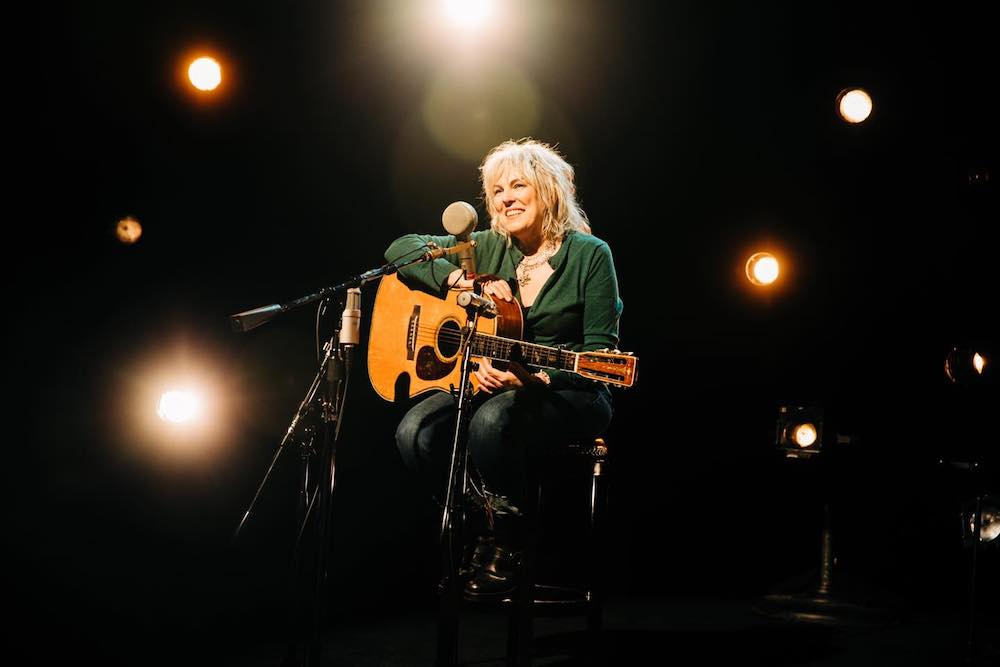

Image from Lucinda Willam’s website.

SP: Your 2020 album, Good Souls Better Angels, is one of the most topical of your career and lyrically conveys many things you were fed up with. Tell me about that.

Williams: Every day there was just more news about all the stuff that was going on, and it was just constant to where I felt kind of burdened by it all and wanted to get some of it off my chest. Kind of purge some of it.

I’d been wanting to write more topical songs. Over the years I wanted to address some issues, but those kinds of songs are hard to write. I wasn’t sure if I could pull it off. I was really inspired and influenced by some of Bob Dylan’s protest songs, the antiwar songs. I grew up with all those. Those songs were really important to me because I was concerned about a lot of these topical issues back then, and I still am today. I’m still that same person I was then. I used to sing his song “Masters of War.” I tried my hand at writing stuff like that and it’s very difficult. You don’t want to make it too hearts and flowery, like ‘brothers and sisters’ and ‘love and peace’ and all that. Dylan did such a good job of writing those kinds of songs—“Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Masters of War” and “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. I was into all that heavily.

SP: What does the title “Good Souls Better Angels” mean?

Williams: I guess it’s kind of a spiritual outlook. We all need all the help we can get. I love songs that address different issues. It’s not really political. It’s as much spiritual as it is anything else. I’ll do “Joy” [in concert]. I’ll do “Man Without a Soul” and “Faith and Grace” back to back. My song “Good Souls” is along the same lines as a song like “Faith and Grace.”

SP: You’re an artist who isn’t afraid to evolve. Why do you like to experiment when making music?

Williams: I love a lot of different styles of music. People might be surprised at the kinds of stuff I like, like some of the hip-hop artists. I love Hispanic music, Brazilian music, world music. That probably comes from listening to a lot of folk music over the years because it’s derived from so many different places. The whole global outlook and connection with things — I like that in music. I like music from different countries and different cultures. I pay attention to all of that. It’s bound to inspire me and come out in my music at some point because I’ve soaked it up for so many years, just different kinds of stuff.

SP: What sorts of things have inspired you to write songs over the years?

Williams: When I sit down to write, it depends on the mood I’m in, but a lot of times it can depend on what I’ve been listening to that week. Maybe if I’ve been in a Neil Young mood, I might write something that’s kind of in that vibe. Everything becomes an influence, an inspiration. It could be a book I read. It could be a movie I saw or an album I listened to. I just like to try different things. I’ve always been like that.

SP: What is your favorite description of how someone has described your voice?

Williams: One time — this is a good one — Emmylou Harris was being interviewed about me. She said, ‘Lucinda can sing the chrome off of a tailpipe.’ I thought that was great.

Album cover from Lucinda WIlliam’s Amazon Music page.

SP: I worked as a music manager at Barnes and Noble in the late 1990s and your album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was selling briskly. You were definitely gaining mainstream notoriety at that time. What was that period like for you?

Williams: You know, all that stuff was going on, but it didn’t really affect me day to day. You don’t really feel any differently. It’s all happening around you. I mean, every so often you realize, ‘Wow, I’m on a different level than I used to be.’ But it’s not like you wake up and go, ‘Okay, this is all different now.’

SP: What do you like about the music industry today that you didn’t when you were younger?

Williams: I can only speak from my perspective, how it’s affected me directly. The big difference there would be that I get more respect than I used to, just because I’m a little more successful and they’ve kind of figured me out now. When I first started out, there was this whole thing where they didn’t know how to market me. They said I fell in the cracks between country and rock, which is true, I guess. But to them it was a problem because they didn’t know where to put me. Like in the record stores—where do you put a record? In the rock section or the country section?

I think over the years that’s gotten better. The independent record label movement really helped a lot. The smaller labels getting more successful and better at what they did. I think when that was happening, the bigger labels were looking at that, saying, ‘Okay, we see what’s happening. This is the way to make this work.’ They could see there was a way to make it work, taking artists like myself and more kind of outsider, different artists who didn’t fit in anywhere and make that work in the music business. I think that part of it changed for the better.

Rough Trade Records really opened the door for me. They were that English independent label. They took me in and gave me a home and put me on the road. They sent me to Europe right away to do shows. They were a great little label. Their whole thing was they just liked different kinds of music. They left themselves open for different ideas and different kinds of artists. It didn’t matter if it was punk or folk or blues or country or whatever. Their feeling was if it’s good, we’ll find a place for it. We’ll support it and we’ll support that artist.

SP: Your dad was a professor of creative writing and a published poet who passed on a love of language and music to you. Tell me about his influence.

Williams: When I started writing songs as a teenager, I started showing him stuff because I wanted to get his approval. I wanted him to think it was good. I didn’t realize it was going to turn into kind of a mentorship, an apprenticeship in a way. He would look at stuff and would point things out to me and say, ‘Well, this is good, but this might be better if you did this here.’ For several years, I would send him my songs before I recorded them to make sure they passed muster. I liked doing it and I think he enjoyed it, too. He loved teaching. He brought that to the table. I was just real fortunate to have that.

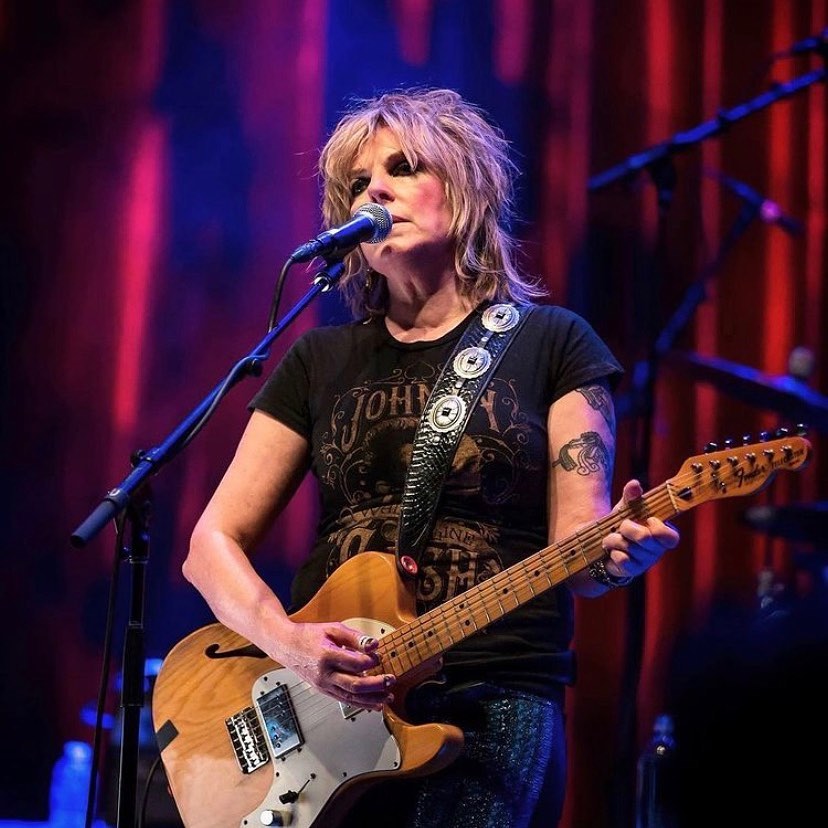

Image by Erik Kabik from Lucinda William’s Facebook page.

SP: Your song “Mama You Sweet” is beautiful. Is it about your mom?

Williams: I wrote that after she passed on. She was a musician. She studied piano as a girl. When my mother and father met, she was majoring in music at LSU. My mother just loved piano. She didn’t play professionally, just around the house and stuff. The genes were definitely there. My music genes from my mother, my literary genes from my dad.

SP: I’m glad you’re doing better since the stroke you had in November of 2020. How did that incident affect your music and life?

Williams: It changed everything, my whole outlook. I’ve been in recovery since then, and that’s been the hardest thing I’ve ever been through. I had to learn how to walk again, which I can do now, but I used to have to use a cane. I couldn’t walk across the floor of the living room without falling down, until I learned how to balance myself. I can’t play guitar, which is the biggest bummer. But I can sing. My voice hasn’t been affected. I can go out and do shows and I’ve got my guys, my band. They back me up. They play and I sing, so it still works. We still go out and do shows and people love it. We just adapted and work around stuff.

It helps me immensely, not just physically but emotionally, to get out and play and sing and do shows. It’s really been therapeutic and very healing to have that outlet. I’m really grateful to my fans for being so supportive through all this.