At the end of the fourth canto of Dante’s Inferno, the author — with the poet Virgil as his guide — meets first poets, then warriors, and finally a third group, great philosophers. At their center is il maestro di color che sanno, “the master of those who know” — Aristotle, so famous that Dante doesn’t bother to name him:

At the end of the fourth canto of Dante’s Inferno, the author — with the poet Virgil as his guide — meets first poets, then warriors, and finally a third group, great philosophers. At their center is il maestro di color che sanno, “the master of those who know” — Aristotle, so famous that Dante doesn’t bother to name him:

When I raised my eyes a little higher,

I saw the master of those who know,

sitting among his philosophic kindred.

All look to him, all show him honor;

there, nearest to him and in front of the rest,

I saw Socrates and Plato…

I cannot give a full account of them all,

for the length of my theme so drives me on

that often the telling comes short of the fact…

Aristotle (384-322 BCE) was a marine biologist who wrote extensively on physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, politics, and ethics. His intellectual descendants include Thomas Aquinas, Karl Marx, and a modern collection of philosophical ethicists. He is still today the subject of philosophical debate.

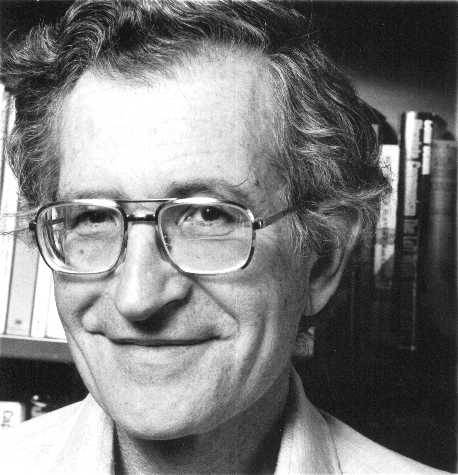

Last week an overflow crowd of 4,000 people bought tickets to the Brecht Forum, held in New York’s Riverside Church, to hear a low-key academic lecture by a soft-spoken 80-year-old, Noam Chomsky, who I and many others think is the proper modern successor to Aristotle as the master of those who know.

Chomsky deserves the title for several reasons — notably his encyclopedic commentary on American politics, since the early days of the Vietnam War — but perhaps even more because as a young man Chomsky did for linguistics roughly what Einstein did for physics. He changed entirely the nature of the field, and his work illuminated what and how human beings know.

Before Chomsky, linguistics was an historical and literary study; Chomsky transformed it into a mathematical and philosophical science. He argued that language was an inborn human trait, unique to the species, and as natural to human beings as flying is to birds. An intelligent visitor from Mars, he has said, would regard all human beings as speaking the same language, with regional variations…

He also argues that in language humans are uniquely creative:

“I think that anyone’s political ideas or their ideas of social organization must be rooted ultimately in some concept of human nature and human needs. Now my own feeling is that the fundamental human capacity is the capacity and the need for creative self-expression, for free control of all aspects of one’s life and thought. One particular crucial realization of this capacity is the creative use of language as a free instrument of thought and expression. Now having this view of human nature and human needs, one tries to think about the modes of social organization that would permit the freest and fullest development of the individual, of each individual’s potentialities in whatever direction they might take, that would permit him/her to be fully human in the sense of having the greatest possible scope for his freedom and initiative.”

It’s for his wide-ranging political and historical writings that Chomsky is best known, and he is properly contemptuous of the “ideological institutions” — academia and the media — that establish the limits of allowable debate on those matters:

“I did some work in mathematical linguistics and automata theory, and occasionally gave invited lectures at mathematics or engineering colloquia. No one would have dreamed of challenging my credentials to speak on these topics — which were zero, as everyone knew; that would have been laughable. The participants were concerned with what I had to say, not my right to say it. But when I speak, say, about international affairs, I’m constantly challenged to present the credentials that authorize me to enter this august arena, in the United States, at least — elsewhere not. It’s a fair generalization, I think, that the more a discipline has intellectual substance, the less it has to protect itself from scrutiny, by means of a guild structure.”

Chomsky is often charged with being a Marxist, but he is in fact a severe critic of Marxism-Leninism — from the Left. I first heard Chomsky lecture 40 years ago this summer, and in that lecture he set out his fundamental political views:

“I think that the libertarian socialist concepts, and by that I mean a range of thinking that extends from left-wing Marxism through anarchism, I think that these are fundamentally correct and that they are the proper and natural extension of classical liberalism into the era of advanced industrial society. In contrast, it seems to me that the ideology of state socialism, that is, what has become of Bolshevism, and of state capitalism, the modern welfare state, these of course are dominant in the industrial countries, in the industrial societies, but I believe that they are regressive and highly inadequate social theories, and that a large number of our really fundamental problems stem from a kind of incompatibility and inappropriateness of these social forms to a modern industrial society.”

He has in fact explained his political position with explicit reference to Aristotle:

“Aristotle took it for granted that a democracy should be fully participatory and that it should aim for the common good. In order to achieve that, it has to ensure relative equality, ‘moderate and sufficient property’ and ‘lasting prosperity’ for everyone. Aristotle felt that if you have extremes of poor and rich, you can’t talk seriously about democracy. Any true democracy has to be what we call today a welfare state — actually, an extreme form of one, far beyond anything envisioned in this century. The idea that great wealth and democracy can’t exist side by side runs right up through the Enlightenment and classical liberalism, including major figures like de Tocqueville, Adam Smith, Jefferson and others. It was more or less assumed.

“Aristotle also made the point that if you have, in a perfect democracy, a small number of very rich people and a large number of very poor people, the poor will use their democratic rights to take property away from the rich. Aristotle regarded that as unjust, and proposed two possible solutions: reducing poverty (which is what he recommended) or reducing democracy.

“James Madison [principal author of the US Constitution], who was no fool, noted the same problem, but unlike Aristotle, he aimed to reduce democracy rather than poverty. He believed that the primary goal of government is ‘to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.’ As his colleague John Jay [first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court] was fond of putting it, ‘The people who own the country ought to govern it.’

“Madison feared that a growing part of the population, suffering from the serious inequities of the society, would ‘secretly sigh for a more equal distribution of [life’s] blessings.’ If they had democratic power, there’d be a danger they’d do something more than sigh. He discussed this quite explicitly at the Constitutional Convention, expressing his concern that the poor majority would use its power to bring about what we would now call land reform. So he designed a system that made sure democracy couldn’t function. He placed power in the hands of the ‘more capable set of men,’ those who hold ‘the wealth of the nation.’ Other citizens were to be marginalized and factionalized in various ways, which have taken a variety of forms over the years: fractured political constituencies, barriers against unified working-class action and cooperation, exploitation of ethnic and racial conflicts, etc.

“To be fair, Madison was pre-capitalist and his ‘more capable set of men’ were supposed to be ‘enlightened statesmen’ and ‘benevolent philosophers,’ not investors and corporate executives trying to maximize their own wealth regardless of the effect that has on other people. When Alexander Hamilton and his followers began to turn the US into a capitalist state, Madison was pretty appalled. In my opinion, he’d be an anti-capitalist if he were alive today — as would Jefferson and Adam Smith.

“Throughout our history, political power has been, by and large, in the hands of those who own the country. There have been some limited variations on that theme, like the New Deal. FDR had to respond to the fact that the public was not going to tolerate the existing situation. He left power in the hands of the rich, but bound them to a kind of social contract. That was nothing new, and it will happen again.”

———

In the summer of 1990 — just before Iraq invaded Kuwait and gave the U.S. government an excuse for war in the Persian Gulf — a partner and I began a weekly hour of political discussion on a community radio station, with the title “News from Neptune.” It was named in honor of Chomsky, who had said that, in the American media, “Either you repeat the same conventional doctrines everybody is saying, or else you say something true, and it will sound like it’s from Neptune.”

The radio program became a newspaper column (in a late, lamented Champaign-Urbana weekly and on the online magazine CounterPunch) and a website. Now it appears on Urbana Public Television, Fridays 7–8 p.m., cable channel six — and online at the website, soon after the cablecast. The subject throughout has been the news of the week (generously interpreted) and its coverage by the media — with Chomsky’s politics as a touchstone.

“… the length of my theme so drives me on that often the telling comes short of the fact…” Comments are welcome to <[email protected]>.

“Experience supports the testimony of theory, that it is the duty of the lawgiver rather to study how he may frame his legislation both with regard to warfare and in other departments for the object of leisure and of peace. Most military states remain safe while at war but perish when they have won their empire … The lawgiver is to blame, because he did not educate them to be able to employ leisure.”

— Aristotle, Politics 7.1334a