I blame Mary-Louise Parker. Really, it’s her fault. The short skirts with legs that go on and on forever, the platform heels, the wavy siren-like tendrils, the off-kilter grin and lilting drawl, and the sort-of-stoned/ sort-of-shell-shocked delivery: they creep into my theatrical psyche and whisper, “Your directing efforts are mine! There is no escape. Just succumb. It will all end well. Trust me…”

Even when I have no idea she’s been involved in a script I’m reading, when I fall in love with a piece, Ms. Parker’s there in the original cast list or the film adaptation: Angels in America, Dead Man’s Cell Phone, and now, How I Learned to Drive. Each play has been touched by her distinctive style and each character bears her delicate mark. I’ve always been attracted to the person at the party who leans against the wall staring at me and seems to know the punch line to every joke I’m about to use as a pick-up line. It’s the “smarter-than-you” smirk that gets me, and Ms. Parker has trademarked that gaze in role after role. She has been my theatrical muse for years, and I really can’t complain. Each of the afore-mentioned Parker vehicles has given me some of the most memorable moments of my theatrical career. The plays she’s touched pierce my heart and uncover my truth, and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive is no exception.

How I Learned to Drive is a play with teeth. It makes you think and feel, and rattles you out of your comfort zone. It’s a love story with thorns that demands attention. The play centers on the narrative of its protagonist, Li’l Bit, an adult survivor of an intense and forbidden first love. Her wounds are visible at the start of the play, and with love and humor, she peels the layers of her diaphanous gown, performing an emotional striptease to the shocking core of an ultimate betrayal. Kay Holley, a member of the Celebration Company’s Board of Directors states, “The play is a sort of love story between a girl and her pedophile uncle. It isn’t always pretty. It isn’t always ugly. It’s just all too true. This script brilliantly captures the way in which a child can be tied into her own bondage with silken thread.” Clearly, this is not The Sound of Music, and submerging ourselves in this world for several months leaves a lasting imprint on all involved. So what makes us work so diligently to produce this Pulitzer Prize winning play, and why should you attend?

For cast members, this show is a labor of love. While the facts of Li’l Bit’s abuse may be atypical, the emotional impact of her saga is all too common. Chris Taber, the actress playing Li’l Bit in The Celebration Company’s production, is an area theatre teacher and was drawn to the project by the script. When she read it for the first time she found, “The script was an intense ride from start to finish and I knew I wanted to be a part of bringing this story to life.” Her portrayal of a girl who is both experiencing her first love and is being manipulated by that love has proven challenging. “She is someone who wants love, understanding.” The actress says as she reflects on her role, “She wants someone to look out for her. I can certainly relate to this. I think we all, as humans, can relate. L’il Bit finds what she is looking for, however ‘wrong’ it may be. I understand making the wrong choice about the significant people we let into our lives.”

Every love story has a lover and every story of abuse, an abuser. In How I Learned to Drive, Peck is Li’l Bit’s first love and manipulative abuser. Those seemingly incongruent parts stem from what playwright Paula Vogel characterizes as “a culture of victimization.” She wrote this play in response to other plays on the topic that vilified the abuser and further weakened and victimized the victim. From speaking to young people about this piece, she observes, “being in that kind of mindset of victimization causes as much trauma as the original abuse.” She wrote this play to counter-act the clear cut “after-school special” portrayal of victim and monster. “I felt it was a mistake to demonize the people who hurt us, and that’s how I approached the play.” Peck is a man with many weaknesses, but he is also a caring and nurturing presence in Li’l Bit’s life. He hurts and supports in equal doses, and Li’l Bit’s response is a combination of admiration, anger, and finally, pity. Sympathy for the devil is more than a mere song title in Li’l Bit’s life. It’s her heartbreak and her redemption.

Thom Miller, the actor portraying Peck, looks forward to an audience seeing this complex character. “I am drawn to the complexity of darker characters and plays. I like the mix of humor and drama and how they affect an audience. It’s a story that I believe people should see. It’s funny and dark and uncomfortable, but ultimately has hope.” And of the character Peck, Miller says, “I think the biggest hurdle for me was to see him as just a man with flaws and, even though they are bad flaws, he is still just a man and not all bad or evil. He does bad things but those bad things are mixed with good and that complexity makes him a very interesting character.”

Thom Miller, the actor portraying Peck, looks forward to an audience seeing this complex character. “I am drawn to the complexity of darker characters and plays. I like the mix of humor and drama and how they affect an audience. It’s a story that I believe people should see. It’s funny and dark and uncomfortable, but ultimately has hope.” And of the character Peck, Miller says, “I think the biggest hurdle for me was to see him as just a man with flaws and, even though they are bad flaws, he is still just a man and not all bad or evil. He does bad things but those bad things are mixed with good and that complexity makes him a very interesting character.”

Now before you start shuttering and backing away from any theatrical experience that doesn’t come with infectiously catchy tunes and a Disney ending, Vogel’s play is not all darkness and sorrow. The hope Miller refers to is reflected in Vogel’s thoughts on the piece. The play, “treads the tightrope between comedy and drama.” Li’l Bit’s quirky take on life, love, and abuse is not without its charm and her humor is her survival tool in the darkest moments of the narrative. Malia Andrus, an actress who plays both the protagonist’s mother and Peck’s long-suffering and oddly patient wife states, “I really like how this story is told in shades of grey. It forces you to question your perspectives about a subject that is typically seen as obviously bad. But it feels real because real life doesn’t have easy answers.” Vogel’s skills of navigating the dramatic and comedic elements of this story are the play’s strength. Her studying of classic narratives, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita are a major influence on this work. “In many ways, this play is a homage to Lolita,” states the playwright. The odd mix of comedy and dread seen in both the Kubrick and Lyne film adaptations trickles through veins of Vogel’s piece. Li’l Bit is both vulnerable and tough, and it’s her gritty fierceness and acid wit that allows her to survive.

Sarah Heier, an actress who plays roles ranging in age from 11 to 65, is a huge fan of the work and encourages all to experience this oddly beautiful piece

I was initially drawn to auditioning for HILTD because I saw a breathtaking production of the show in 2005 at the Topeka Civic Theatre in Kansas. It’s one of those plays where I remember having a transformative experience. I remember it being chilling, funny, and thought provoking in only 90 minutes. It makes you think about one’s psychological and physical desires. It’s beautifully written.

The story of a girl who longs for love and acceptance and searches in some dangerous places to find it is a common theme many can identify with. Her search for love comes from insecurity over being “a cracker,” an outcast, and her love of education and language are her ticket out of these states. Being an outcast is tricky because sometimes you don’t know anything’s amiss until it’s too late. For Li’l Bit, the realization happens during her freshman year at college. She sees how her classmates talk about their families and their pasts, and realizes she’s been duped. The family she trusted is full of cracks and booby traps. The foundation they’ve laid is unstable, crumbling around her. Their love is a lie, and the man she has loved and trusted most is the biggest offender.

For me, this is a deeply tragic love story, and a narrative with a great deal of personal resonance. Personally, I’ve had my own brush with victimization at an early age. The abuser was attractive and clever, someone seemingly worthy of trust. My feelings for him blinded me to the malevolent intent of his affections until it was too late. It took years to admit to the victimization. It’s taken even more years to forgive myself for trusting his words, his gaze, and his smile. Like Li’l Bit, this abuse happened before our culture had a definition of the act. Our healing and survival were achieved without a map. Li’l Bit finds healing in the moment she has compassion for her abuser. It’s a brave and difficult response, one I haven’t personally achieved.

As Vogel portrays, monsters are not as clear-cut as we may think. Villains may be dashing and even sweet in their actions. They have parents and friends and families who love them. They have jobs and churches that value them. They can’t be picked out of a crowd, and Vogel’s play makes that point infinitely clear. When the abuser is a news headline, it’s easy to make them a monster with claws and fangs, a being so foreign to our everyday lives that we couldn’t imagine meeting one. So we sleep soundly, knowing we are untouchable. Safe. The danger is these people don’t radiate evil or damage. They don’t wear signs that warn the public of their intent. They are walking in the hall next to us, sitting in our classrooms or office spaces, and standing in line next to us at our banks and supermarkets. On occasion, they may even live with us and share our homes and beds. Victims and victimizers are all around us, and their stories of survival and struggle deserve our consideration. How I Learned to Drive is a plea to our humanity for compassion and awareness. It puts a human face to the headlines. For this reason alone, it deserves our attention.

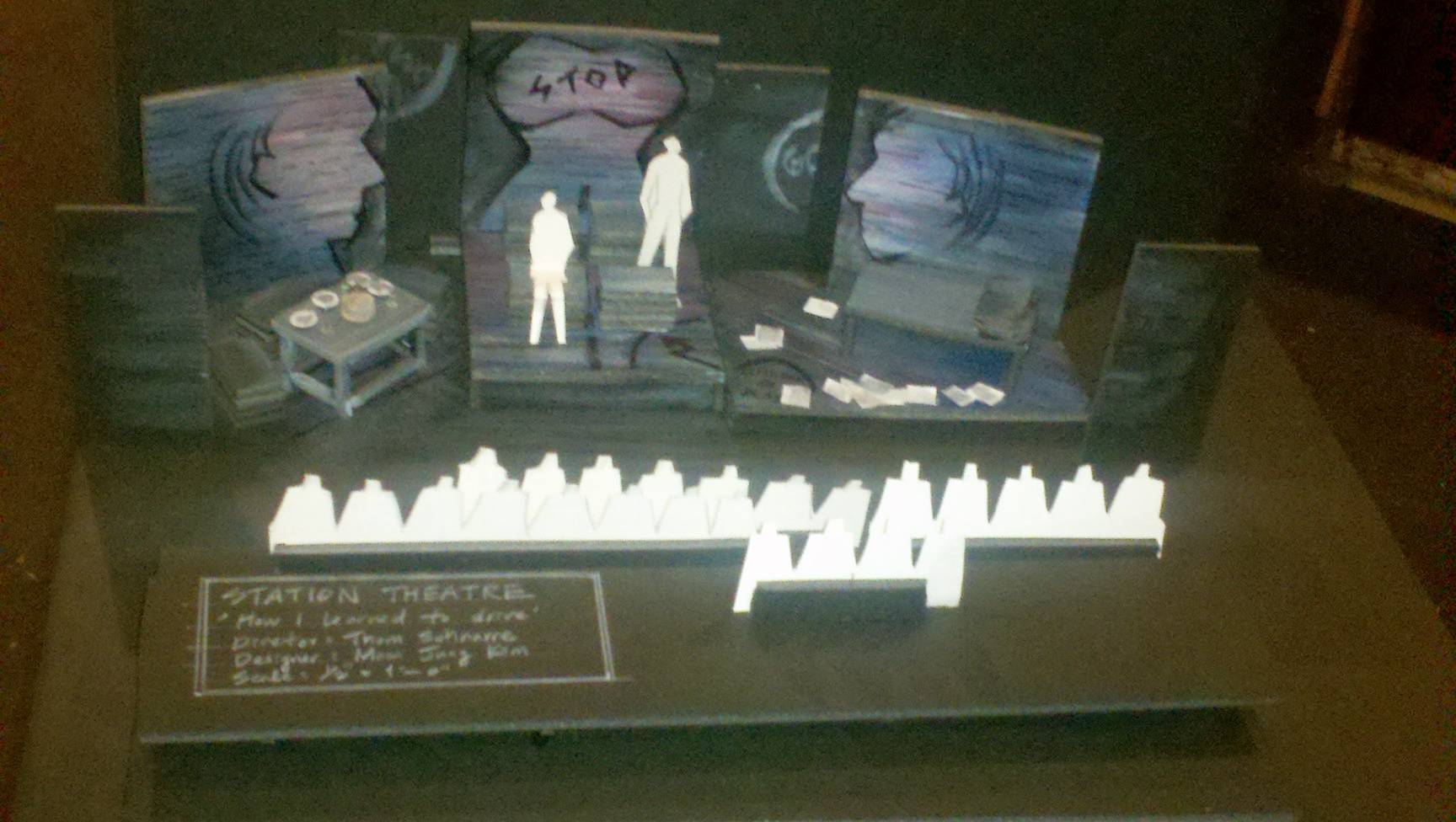

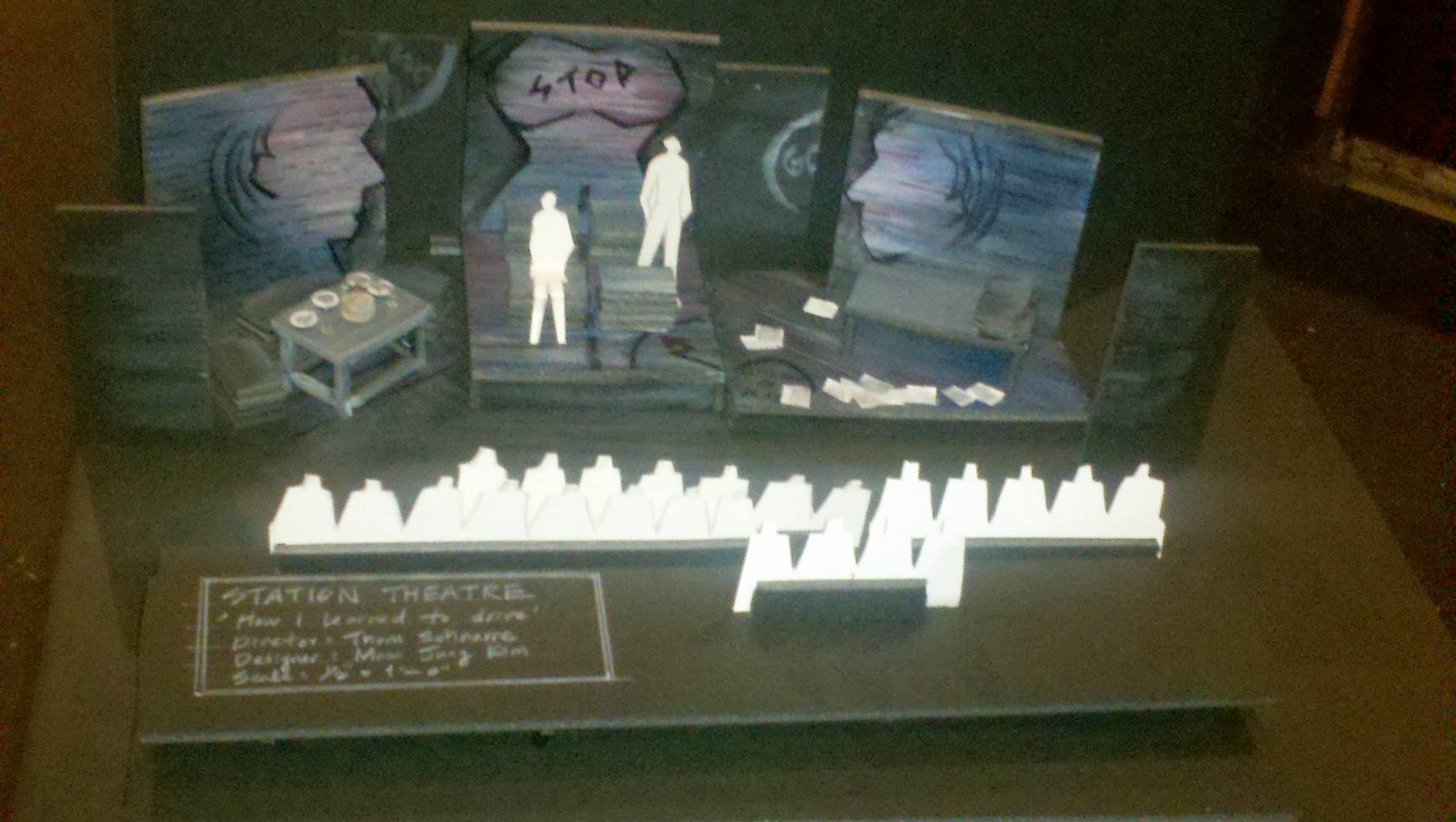

How I Learned to Drive will be performed by The Celebration Company at The Station Theatre in Urbana, October 4–7, 10–14, and 17–20. All performances are at 8:00 p.m. Tickets are $10 on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays, and $15 on Fridays and Saturdays. Adults over 62 and students receive a $1 discount with ID. There is free parking at Save-a-Lot. Due to the intimate nature of the space, reservations are recommended. For reservations call (217) 384-4000 or reserve online.

Thom Schnarre is the director for How I Learned to Drive.