The last day of the Planet U conference focused on considering how we can move forward from here. Again, I won’t attempt to recap all the sessions, but would point you to these online resources:

The last day of the Planet U conference focused on considering how we can move forward from here. Again, I won’t attempt to recap all the sessions, but would point you to these online resources:

- www.chicagoclimateaction.org — Suzanne Malec-McKenna gave an excellent presentation on Chicago’s work to understand the upshot of climate change for the Chicago region and plan on how to mitigate the impacts, as well as detailing the actions the city has taken so far. It’s a great model for taking these huge, abstract problems and translating them into a concrete, human-scale plan of action.

- http://www.planetu.illinois.edu/videos/archive/ — I cannot recommend Peter de Menocal’s presentation from Friday about the African Humid Period, its abrupt end, and the cultural implications of the transition highly enough. The entirety of Africa was covered with vegetation for 10,000 years in the recent past. How did I not know about this? He is an unbelievably clever man. (Hopefully the archived videos will be posted soon – ed.)

Stephen Long gave a presentation on the excellent research he’s been conducting at Illinois regarding the effects of increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and ozone on our staple crops, particularly soybeans. The 2007 IPCC report postulated that as a positive benefit of climate change, crop yields would increase. This prediction was based on studies in greenhouses, but Long noted that these don’t come close to capturing the complexities of a field. Seed companies would not have such extensive outdoor testing facilities if greenhouse studies were sufficient. So he and his graduate students and colleagues designed a system that surrounded a small plot with a series of tubes that release enough carbon dioxide to maintain an ambient concentration of 550 ppm, a likely climate scenarios in 2050. It is all just exceptionally ingenious and you can read all about it at his SoyFACE site.

Stephen Long gave a presentation on the excellent research he’s been conducting at Illinois regarding the effects of increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and ozone on our staple crops, particularly soybeans. The 2007 IPCC report postulated that as a positive benefit of climate change, crop yields would increase. This prediction was based on studies in greenhouses, but Long noted that these don’t come close to capturing the complexities of a field. Seed companies would not have such extensive outdoor testing facilities if greenhouse studies were sufficient. So he and his graduate students and colleagues designed a system that surrounded a small plot with a series of tubes that release enough carbon dioxide to maintain an ambient concentration of 550 ppm, a likely climate scenarios in 2050. It is all just exceptionally ingenious and you can read all about it at his SoyFACE site.

The upshot of all this? Soybeans do yield more heavily at higher carbon dioxide concentrations, but this benefit is balanced by inhibition of soy’s natural defenses against pests, delayed crop maturation which makes soy more vulnerable to frost, and degradation of the legume’s quality, particularly in calcium levels which are important for those using soy as a dairy substitute.

Susanne Moser ended the conference with a detailed look at the current state of play, politically and socially, with regard to climate change. Her figures were, on the whole, dismaying. If every country in the world did everything each is currently promising to do, we would reach a carbon dioxide concentration of 750 ppm by the year 2100. This would translate to an increase in average temperature worldwide of 4.5 degrees Celsius, more than twice as much as the two-degree increase that the European Union has marked as its threshold above which the consequences become unacceptable.

Susanne Moser ended the conference with a detailed look at the current state of play, politically and socially, with regard to climate change. Her figures were, on the whole, dismaying. If every country in the world did everything each is currently promising to do, we would reach a carbon dioxide concentration of 750 ppm by the year 2100. This would translate to an increase in average temperature worldwide of 4.5 degrees Celsius, more than twice as much as the two-degree increase that the European Union has marked as its threshold above which the consequences become unacceptable.

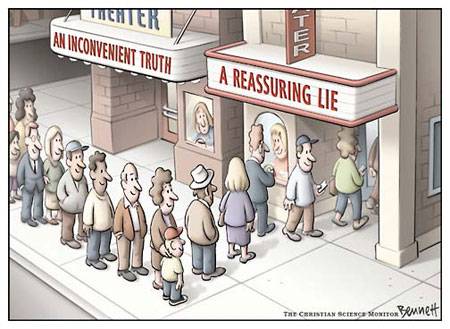

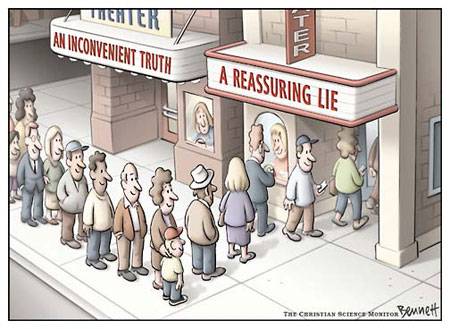

While social awareness of climate change has reached saturation levels, neither the strength of the scientific consensus regarding its unequivocal existence and human-made nature nor the magnitude of the danger global warming poses is understood by the American public. According to a survey conducted this year, only six in ten believe that climate change is caused by human activities. Only 47 percent believe that most scientists agree on the subject. Only ten percent believe global warming will personally affect them a great deal.

The average American emits 20 tons of carbon dioxide per year. The current world average is four tons. In order to get down to that level, you would have to select from one of the following four activities:

- drive 10,000 mi. per year @ 30 mpg

- fly cross-country twice

- heat and air condition the average American home

- light the average American home

You may select one and only one. Now consider that we need to bring per capita carbon emissions down to ONE ton per year to stabilize carbon levels in the atmosphere. According to Moser, “The emissions of the future rich must come down to the emissions of today’s poor.”

Moser called for a social and political effort in the US on the scale of the mobilization for World War II. She outlined a ten-point plan with which she, if given the authority, would try to build the consensus needed to support high level leadership and to motivate people to do their bit and change their behavior.

According to Moser, this is a challenge that is unlike anything we’ve ever faced. As hard as we try, things will still get worse. So how do we stick with it? For Moser, the path of hope entails four elements: a diagnosis, a vision, a planned trajectory, and a strategy for the setbacks. If we can construct this, then we have a chance.

This last bit moves from Moser’s presentation to my own personal opinion. It seems clear to me that we in the industrialized world won’t be able to maintain our accustomed standard of living, much less bring people in the developing world up to these levels of consumption. Technological advances will help to close this gap, but reducing our carbon footprint to one-twentieth of current levels will require that we drastically reduce the absolute amount we consume.

When I look back at the energy crisis of the 1970s, one of the things that strikes me is that every political leader who called for austerity as part of the response was thrown out of office as quickly as possible. Jimmy Carter in the US, Joe Clark in Canada, and Jim Callaghan in the UK come to mind, and it’s likely that there are more in nations with which I’m not as familiar.

Austerity runs very strongly against the grain in our politics and culture. Any regime that imposed such measures, such as the wartime rationing in Great Britain and the US, had to be sweetened with the promise that soon all this scrimping and saving could end. But, barring a technological breakthrough which could remove carbon dioxide and methane from the atmosphere on a huge scale, we will never see a climate like the one we have now for at least 1,000 years. Whatever level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at which we stabilize will be roughly where we stay. So if we have to live more austerely, how will we arrange to do so? Is capitalism sustainable under such a constraint? Is democracy sustainable under such a constraint? We shall see.

If you enjoyed this article, see Michael’s summaries of the first two days of the Planet U Conference: