Twenty five is one of those milestone birthdays that doesn’t really feel like a milestone (unless you’re super psyched to finally rent a car on your own, I suppose). But in terms of works of art — and especially albums — that 25th anniversary is something remarkable, and something to make a special note of.

Great albums get to celebrate such a milestone for a few reasons. First, an album that still has an impact a quarter of a century after its release is a testament to the talent, ambition, luck, and “lightning in a bottle” shared amongst the creators. And second, an album that is remembered and appreciated for 20-plus years has no doubt become a core memory for music fans. Discovering great music is in many ways discovering something about one’s self; that piece of art stays with us and even helps to shape and form so much of what we become as we grow older.

Yes, that’s a hell of a preamble, but I think you’ll agree that local rock heroes Hum deserve no less. And perhaps deserved quite a bit more.

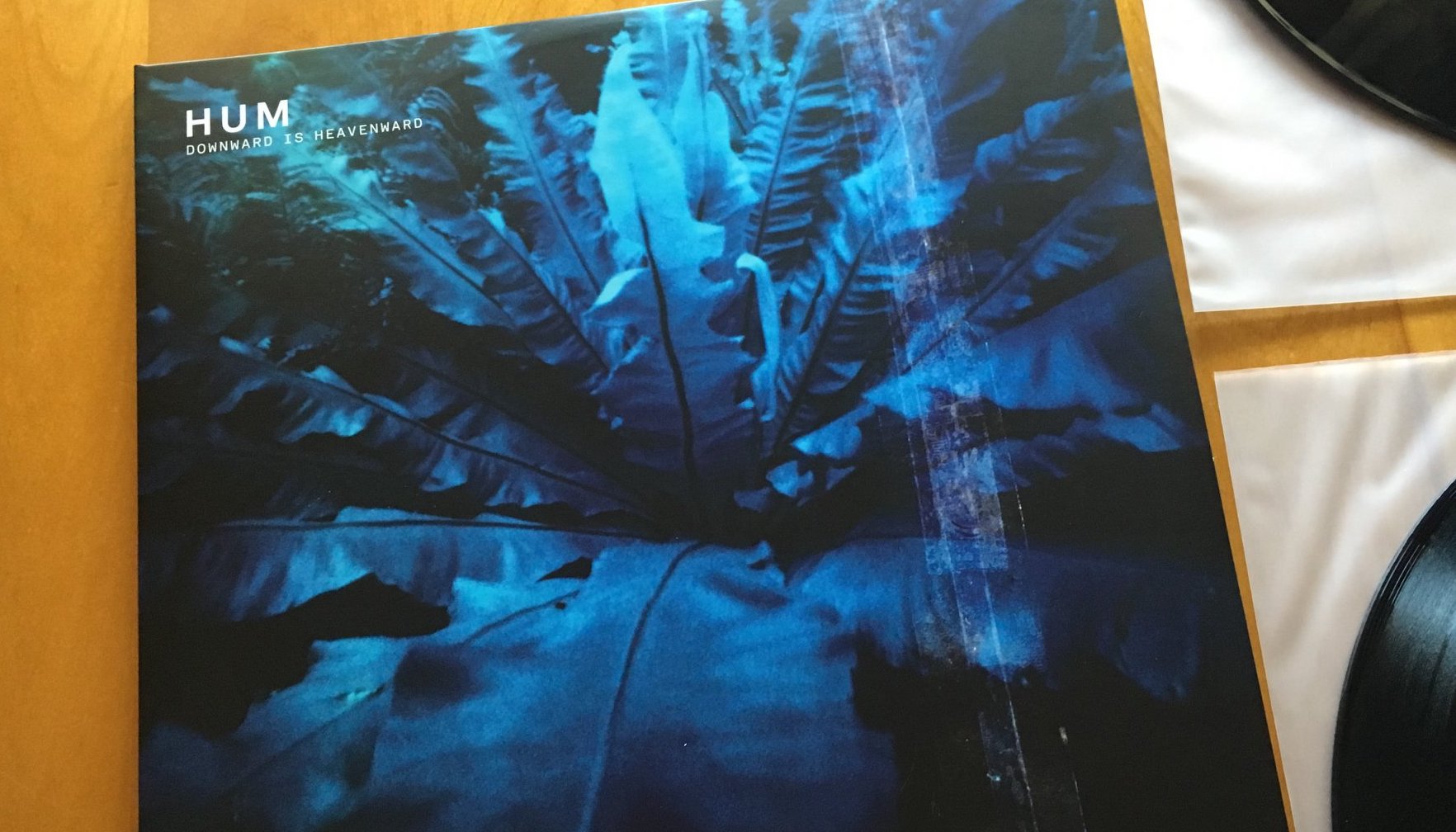

Downward is Heavenward, Hum’s second major-label release, began sliding into fans’ CD players on January 27th, 1998. Unfortunately it never reached the chart heights or sales volume of its predecessor, You’d Prefer an Astronaut, and the band was dropped from RCA shortly after.

The lackluster sales make little sense when contrasted with the album’s critical reception. Pitchfork reviewer Brent DiCrescenzo summarized the album by saying, “A listen to Downward is Heavenward actually scrubs off a layer of skin, yet Hum still manage to infuse grace and control into their skyward swirl.” Ned Raggett of AllMusic.com emphatically states that Downward “isn’t merely the group’s best album, but a lost classic of ’90s rock, period,” a sentiment echoed as recently as a 2015 concert review of the band’s performance at The Regent in L.A. (in which writer Chris Barton also emphasizes the band’s impact by noting that Deftones’ singer Chino Moreno considers Hum a significant influence on his band).

As with most landmark albums, Downward is not only sonically excellent, but also stingingly poignant and simultaneously open to interpretation. Hum’s distinct soundscape is present, backbeat bludgeoning its way through a sonic wall that makes you envision an auditorium full of amplifiers and speaker stacks. Lyrically, themes of love, loss, heartbeats, and heartbreaks wind their way through the tracks, all of it swirled and muddled in the celestial imagery that is central to Hum’s sound.

“Isle of the Cheetah” opens the album with a floaty, ethereal, odd-time vibe, transitioning with a stomp-box click into the polished, fuzztastic distorto-rock that fans had come to love on their prior releases. The soundscape is as broad as the sea that Matt Talbott conjures in the lyric “Your ocean spreads out on sunbeams … Radiant, knowing …”

“Comin’ Home” teases with 18 seconds of gentle introduction before powering its way into listeners’ ears like a tunnel-boring machine. More odd time signatures and furious guitars slam through the speakers, with a hint of screamo in the middle as Talbott cuts loose on the microphone.

In stark contrast to the first two tracks, “If You Are to Bloom” settles into a seemingly comfortable groove while lyrically exploring themes of unimaginable loss. Similarly, “Ms. Lazarus” features a dreamy sort of tone, but the chords and melody feel uneasy beneath it all. The sense of loss, regret, and sadness is made evident by the lyric, “The way your headstone shines; I only wish that it was mine.”

The lyrics to “Afternoon with the Axolotls” give the album its title as well as an ominous sense of tragedy; the helicopter at the end of the track inviting listeners to ask what just happened, or what is about to happen.

Maybe it’s just the number of times I played the song on the old Illini Inn jukebox, but I’ve always felt that “Green to Me” should have (or at least could have) been a bigger hit than “Stars.” This is straight-ahead rock that seems perfect for those Midwestern nights when the car windows go down and the stereo gets turned way up. Lyrically we may be awakening from a dream or coming out of a drug-induced haze. As with the other tracks, there is room for listeners to come back again and again, finding and defining their own interpretation of the song and the story behind it.

“Dreamboat” might be as straightforward of a love song as you’ll ever get from Hum, while “The Inuit Promise” captures a snow-globe portrait of lovers clinging to each other through a seemingly Arctic winter.

The melancholy of “Apollo” conveys the complicated feelings of leaving and returning, and the strain it places on emotions and relationships. Then, finally, we’re back to driving guitars and drums with “The Scientist,” which I understand as a commentary on how uncontrollable chemistry between two people can be, packaged in a story of experimentation gone awry. But, of course, you may arrive at something different that is also “Too much, and too late.”

In the 25 years since Downward’s release, Hum have nearly faded into obscurity, reunited for some bombastic live performances and brief tours, reissued the album on vinyl, dropped a surprise pandemic album that elated fans and critics alike, and lost a cornerstone of their rock-solid foundation in the unexpected and untimely passing of drummer Bryan St. Pere at the age of 52. Through these and countless other events, Hum’s distinct spacegaze brand of heavy alt rock has remained an influential and consequential part of the music world. And Downward is Heavenward stands as perhaps the best example of it: an album that is not only a Chambana classic but a revered record in pockets of the music world at large.