This is part two of a series on the state of poverty and hardship in the east central Illinois area. For the first part, please see Anna’s first piece here.

Trying to Keep Food on the Table

It is the third Thursday in August of 2010. The upstairs of Wesley United Methodist Church is full of people waiting to get food from its pantry program. The program’s head, Donna Camp, takes the stage in the large room and introduces me on the public address system. She tells the pantry clients that I am writing an article and would like to interview them about what it is like to try to live on food stamps and that they need not give their names.

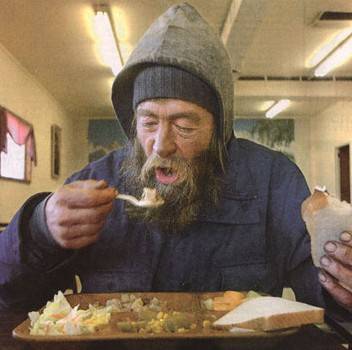

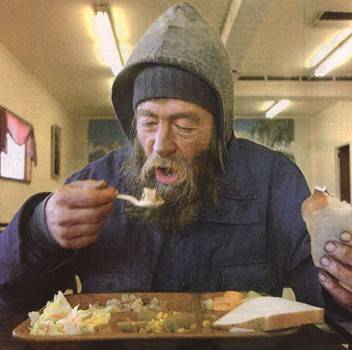

No one wants to talk. Some people look down at the tables in front of them. Others look at the open windows hoping for a breeze that is not to be found. It is 90 degrees, 93 with the humidity factored in, and Wesley is not air conditioned. No one is here tonight who doesn’t have to be. But each month, people from some 300 households have to be at Wesley because they have run out of food.

Donna tells me that Wesley’s 100 volunteers actually start working at noon the day before, unloading two to three trucks and unpacking boxes to set up the “shopping area” at the rear of the church. Much of the food comes from the Eastern Illinois Foodbank (EIF) in Urbana. But as big as the Wesley pantry operation is, it is far from the largest in Champaign-Urbana. That distinction belongs to Salt and Light, which is across the interstate and serves 400 households each Wednesday.

Donna wishes me luck in finding people to interview and rushes back to the front of the church to check on how many people are here for food. She is concerned that the pantry may not have enough tonight. School started only yesterday in Urbana and today in Champaign, so many families whose children receive free breakfasts and lunches during the school year have less than usual in their cupboards this month. Despite the common perception that the holidays are a time of great food need, summers are actually worse.

As the pantry clients file through church meeting rooms and hallways, they fill their grocery bags with canned soup, peanut butter, macaroni and cheese, pasta, dried beans, and canned vegetables. One of the local Schnuck’s grocery stores has donated bread this month. There also is canned tuna and lettuce tonight, but only in limited quantities. The fact that the pantry has them at all is a testament to the commitment of its donors. Protein and produce are costly items, even when acquired through foodbanks like EIF. EIF helps programs stretch their dollars by subsidizing the grocery items it distributes to them. Because of this, programs like the Wesley pantry can acquire groceries for less than a third of what it actually costs to handle them, says EIF Marketing Director, Cheryl Precious.

Down the hall at Wesley, the small bottles of shampoo and shave gel in one of the rooms represent luxuries to many clients because these and other nonfood items like toilet paper, facial tissues, laundry soap, and cleaning products aren’t covered by food stamps.

Alcohol, tobacco, vitamins, medicines, and pet food also aren’t covered. And, with exceptions for some homeless, disabled, and elderly recipients, food from restaurants and delis also is not allowed. Despite what some talk show hosts claim, no one is getting rich from food stamps. The maximum allotment for an individual is just $200 a month. Most people receive less, on average about $120 a month, says Precious. More often than not, their funds only last about two and a half weeks. That’s where foodbanks like EIF come in. Foodbanks receive food donations and acquire food at a discount for soup kitchens, pantries, and other programs to distribute.

Since 2008, EIF has invited community residents to participate in the SNAP Challenge. SNAP is the acronym for the United States Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is formerly and more commonly known as the food stamp program. The original program which used actual stamps was started at the end of the Great Depression in 1939 and ended in 1943. The modern program was begun in 1961. The stamps are long gone, having been replaced with swipe cards with personal identification numbers.

The program is administrated by the Department of Human Services. Participation has been trending upward since 2001, growing at rate of nearly 18,000 people a day this summer. As of August, 42.39 million people comprising 19.7 million households were receiving assistance. And though food prices spiked sharply in 2008, SNAP benefits were not increased until April 2009, when the average benefit went from $25 to $30 a week.

What does $30 a week cover? Not Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette reporter Meg Thilmony’s morning cup of decaf. Thilmony made a valid effort in the SNAP Challenge by eating black bean burgers and textured vegetable protein sloppy joes. But, by day six, she was craving cookies, meat, fish, fruit, and soymilk.

Thilmony failed the challenge on several days by accepting food from others: dinner at her parents’ home and pizza at friend’s party; as well as snacks like cake from a friend and a muffin leftover from a staff meeting. When she was able to comply, Thilmony wrote in her blog that it was only because she had access to several resources, not the least of which were gas and electricity because she could afford to pay her utility bill. She also owned a slow cooker, which could be considered an expensive appliance for someone with limited means. Access to a car and gas allowed her to shop at a bulk foods store in an Amish community an hour out of town. And, she noted that her single, full-time job allowed her to be able to cook both before and after work, in addition to providing some relief from obsessing about food.

Jacqueline Hannah, manager of Common Ground Food Co-op in Urbana, also took the challenge to see whether she could continue to eat locally and organically on $30 a week. If anyone could accomplish this, it would be Hannah, who teaches the co-op’s popular “Eating Healthy on a Budget” class. Because she also develops recipes for the co-op’s Food for All Program, which cost out to $2 or less a serving, Hannah had the advantage of not having to obsess as much about her meals.

Though challenge participants are supposed to avoid using food already on hand, Hannah opted to use produce from her garden. Technically food producing seeds and plants are permissible purchases for SNAP recipients. However, many do not have access to gardening spaces and most crops take months to mature. Gardening also isn’t possible year-round in many parts of the country. But, canning and freezing supplies that would extend participants’ access to their crops year-round aren’t covered under the program.

Even with her experience and garden, Hannah found she often lacked enough time to properly plan her meals and it began to show over the course of the week. The scrambling and the frazzled feeling generated by it only “led to more hunger and distraction,” she wrote in her blog, The Hannah Café.

Still, Hannah managed to eat better than most who participated in the SNAP Challenge which included thousands of people from across the country. Ashley Cullins, Development Coordinator for Lakeview Pantry in Chicago recorded her food consumption on Lance Armstrong’s livestrong.com website. Cullins missed her target goal of 1,600 calories per day by almost half. “I was hungry, grumpy, and lonely,” wrote Cullins on Lakeview’s blog, noting that if it weren’t for volunteering and board meetings, she would have only seen her friends once during the month. “Having to continually turn down my friends did not go over well. If they didn’t know it was temporary, it may have done permanent damage to some relationships,” she wrote.

Hannah, Thilmony, and Cullins were able to empathize with SNAP recipients, which is the goal of the challenge. But the challenge cannot simulate the full stress of living on SNAP. That’s because at the end of the week, they had full cupboards and the peace of mind that comes with that, says Precious. They knew their circumstances were going to improve.

In Urbana, Robin Arbiter knows all too well what it’s like to be on SNAP. Depending upon her health and job prospects, she has been on and off the program for decades. Recently diagnosed with brain seizures, she returned to the program in late-October.

Over the years, Arbiter has worked on issues related to homelessness and volunteered as a community advocate for low-income and disabled residents. Being on food stamps is isolating, she says. Arbiter thinks the name change to SNAP is ridiculous, “As if it isn’t hard enough for people to locate telephone numbers when they need resources for food.”

According to Arbiter, food stamps are problematic because the cooperative instinct to overcome obstacles by pooling resources generally strengthens families and communities and this kind of activity is prohibited by the program.

If you knew that your neighbor was having a hard time financially, you wouldn’t think twice about making a big pot of soup and taking them half. However, sharing food stamps with someone else can cost you your benefits if it is reported, says Arbiter. There is no consideration regarding the ethics of the exchange–whether it was done to help someone in need or whether it was done at a fair exchange rate.

She explains that taking chances becomes attractive when people have little to negotiate with. When money is tight, people turn to grocery store credit cards, pawn shops, payday loan businesses, and other predatory lenders. “People deal, by not dealing and that makes it worse,” says Arbiter. The short term solutions available to poor people are very costly and can exacerbate their problems over the long-run. Eventually they run out of budget for the coming month to tap into, she says.

Similarly, there is a community marketplace where food stamps become a negotiable asset, says Arbiter. Once in a while, people trade portions of their food stamp benefits for cash which could cost them their food assistance if it was discovered. But trading may appear worth the risk when there isn’t enough medication or gas or something else, she says, noting that turning to addictive substances is a common coping mechanism for the stress and depression that accompany poverty.

Arbiter tells of an acquaintance who attempted to trade some of his SNAP benefits, and was exploited when the recipient refused to give back his card. He feared telling authorities what had happened and went without his benefits for the better part of a month, she says.

Because Arbiter just received her benefits and went shopping, her cupboard and refrigerator were stocked when I visited her in late October. She also had some produce and dried herbs from her garden plot. That wasn’t the case for her neighbor, Beth Cain, who was running out of food. Cain recently went on disability and is trying to figure out how to pay off $1,000 in outstanding medical debt so she can receive some needed dental care. Going on disability provided her with a small amount of additional discretionary funds to buy some “luxuries” like a new shower curtain to replace the 10-year old one in her bathroom, a pair of waterproof boots for winter, and some name brand shampoo. However, it reduced her SNAP benefits by more than half to just $80 a month.

Beth and Robin are single so they do not qualify for supplemental food assistance programs like Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) which can provide slightly more food money for families with infants and children.

The application process itself for assistance can be daunting. There are people in my neighborhood who qualify for some level of assistance, but who think the paperwork involved outweighs the benefit, says Arbiter. “Ironically they will tell you that they needed food stamps when they were raising children, but that food stamps are not worth the hassle now, even though they may be resorting to grocery store credit cards and payday loans just to keep food in the house.”

“A lot of people are intimidated about giving out information without a guarantee of assistance,” says James Tropper a University of Illinois junior who volunteers with the Wesley pantry. Pride is an issue as well. Many people would never apply for themselves, but will apply for their children.

Tropper is one of many individuals at area agencies and programs who assist people in applying for benefits. You can see just how little money you would have to earn to qualify by plugging numbers into the Department of Human Services’ SNAP calculator Because of the heavy case loads, Champaign County residents often have to wait months for benefits.

In the meantime, EIF has increased the amount of food it is able to distribute to Wesley, Salt and Light, and the other 218 programs it serves by nearly a million pounds a year for the last several years. However, the need is simply growing too fast. To get food into areas not served or underserved by nearby pantries and programs, EIF finds sponsors and sends out mobile food pantry trucks. Last weekend, it sent a truck to Danville with food for approximately 200 families. Volunteers were able to provide food for 210 families, some 653 people. However, 250 families showed up.

“People were lining up even before the truck arrived,” says Precious. “It’s always a tough thing to tell people at the back of the line that they there is no more food left.”

Last year, EIF distributed 6.2 million pounds of food in Champaign and 13 other counties. However, using data from its hunger study survey and its total service numbers, Precious estimates the need could be over three times that.

Next: New Tools in the Toolbox

This piece was crowd-funded by Smile Politely readers through a collaboration with Spot.us. You can read this story on Spot.us and read the list of contributors here. Thanks to Spot.us, and our generous readers. Let us know if you have an idea for an investigative piece (that you or someone else could report on) that you’d like to see us pursue.