Nicole Anderson-Cobb and Latrelle Bright are Spring 2022 Artists-in-Residence at Allerton Park. They’re a collaborative partnership awarded a residency as part of the program, Rooting A Deeper Connection, which “highlights and celebrates the arts and study of nature within Black and Latinx communities.” Generally speaking, artists often use residencies as a way to disconnect from responsibilities (and people) in order to complete a proposed project. Anderson-Cobb and Bright, however, are using this residency as a platform for research and exploration with the intent of presenting this research at a later time, likely fall 2022.

If those names sound familiar to you, then you’ve been paying attention to arts and culture in Champaign-Urbana. Anderson-Cobb is a writer, journalist, playwright and contributor to Smile Politely; she’s also a University of Illinois alumna. Bright is a theater maker and storyteller in C-U — you’ve seen her directorial work most recently at the Station Theatre, and read about it on SP. She is also a teaching assistant professor of theater at the U of I.

The project that Anderson-Cobb and Bright are undertaking is organized around a series of questions they proposed:

What are our (black folks) historical relationships to water and the woods in the United States of America? What hinders black folks from taking advantage of available nature preserves in this region? What is the invitation (or lack thereof) to folks of color in Central Illinois? What is required to access the park? What role must Allerton Park and Retreat Center play in making a safe space for black folks? How do we “value history” and “sustain and promote the legacy of Robert Allerton Park” a space, a sanctuary dare we say, for communing with nature in a harried world and examine its threads within the fabric of a system that privileged white men and displaced indigenous peoples?

Who are the gods?

What are the lies?

In order to address those questions, the two have been looking into the history of the land, particularly before and leading up to the founding of Monticello in 1837.

Allerton Park’s residency is only three weeks long, but Anderson-Cobb and Bright have been making the most of that short amount of time, spending a lot of it in the archives of Piatt County Historical & Genealogical Society, learning about the founding and history of Monticello, and by extension, Allerton Park.

Photo by Jessica Hammie.

Last weekend, they presented a first draft performance of their findings to a small group of invited guests, entitled Beyond (Land) Acknowledgement. The performance took place in the Allerton Park dwelling they are staying in for the residency, and offered an intimate setting in which they, as performers, could present difficult and complicated material research to a sympathetic and open-minded audience. It was an opportunity to get a sense of how people may respond to the content and gain valuable feedback on potential future routes of exploration both conceptually and practically, with regards to building a public-facing production or installation.

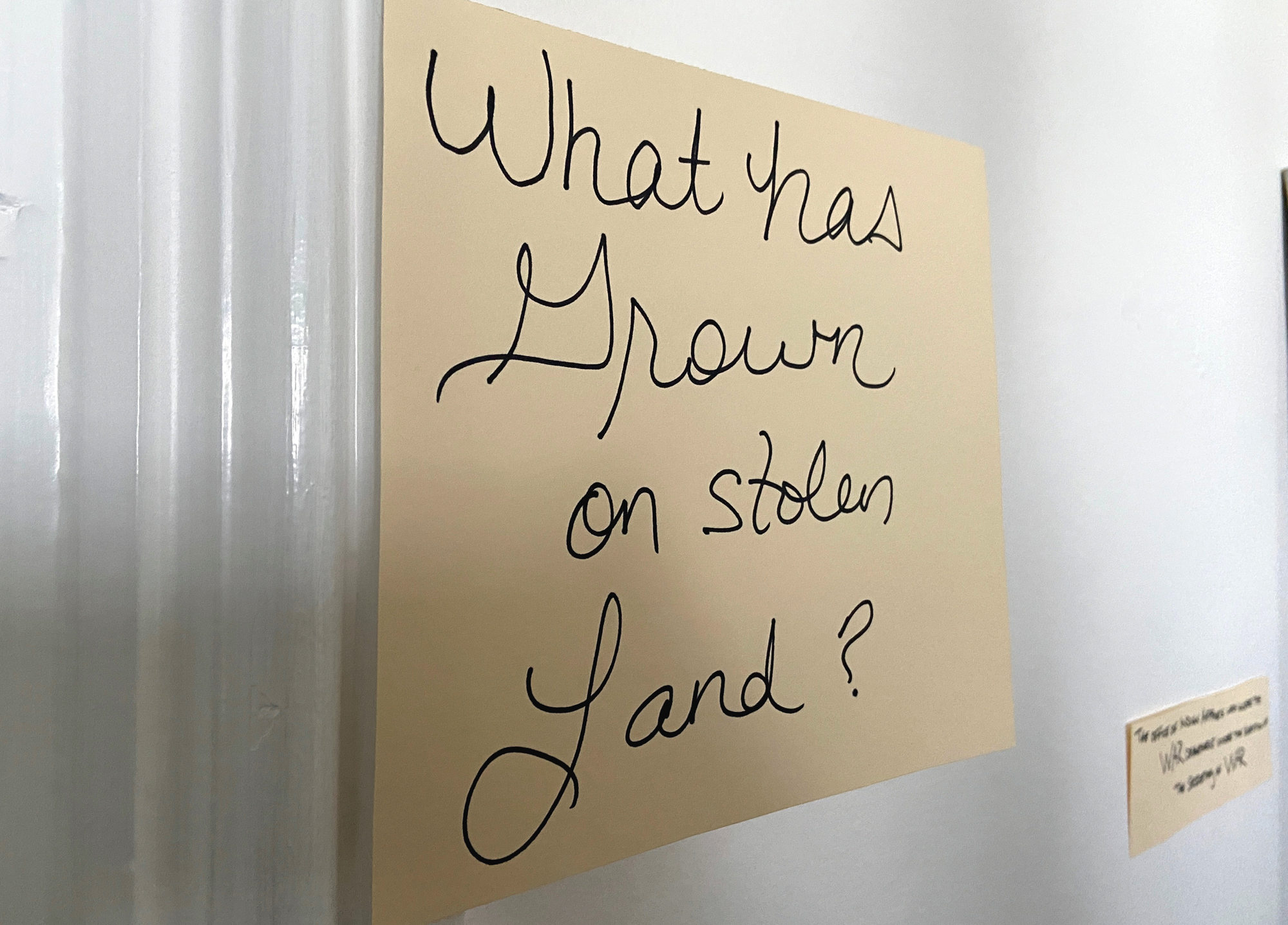

This particular performance was inspired by land acknowledgments, how they are not universally embraced, and the fact that nearly all events hosted by the University of Illinois begin with one. This performance took that framework and was further organized around the question, “What has grown on stolen land?”

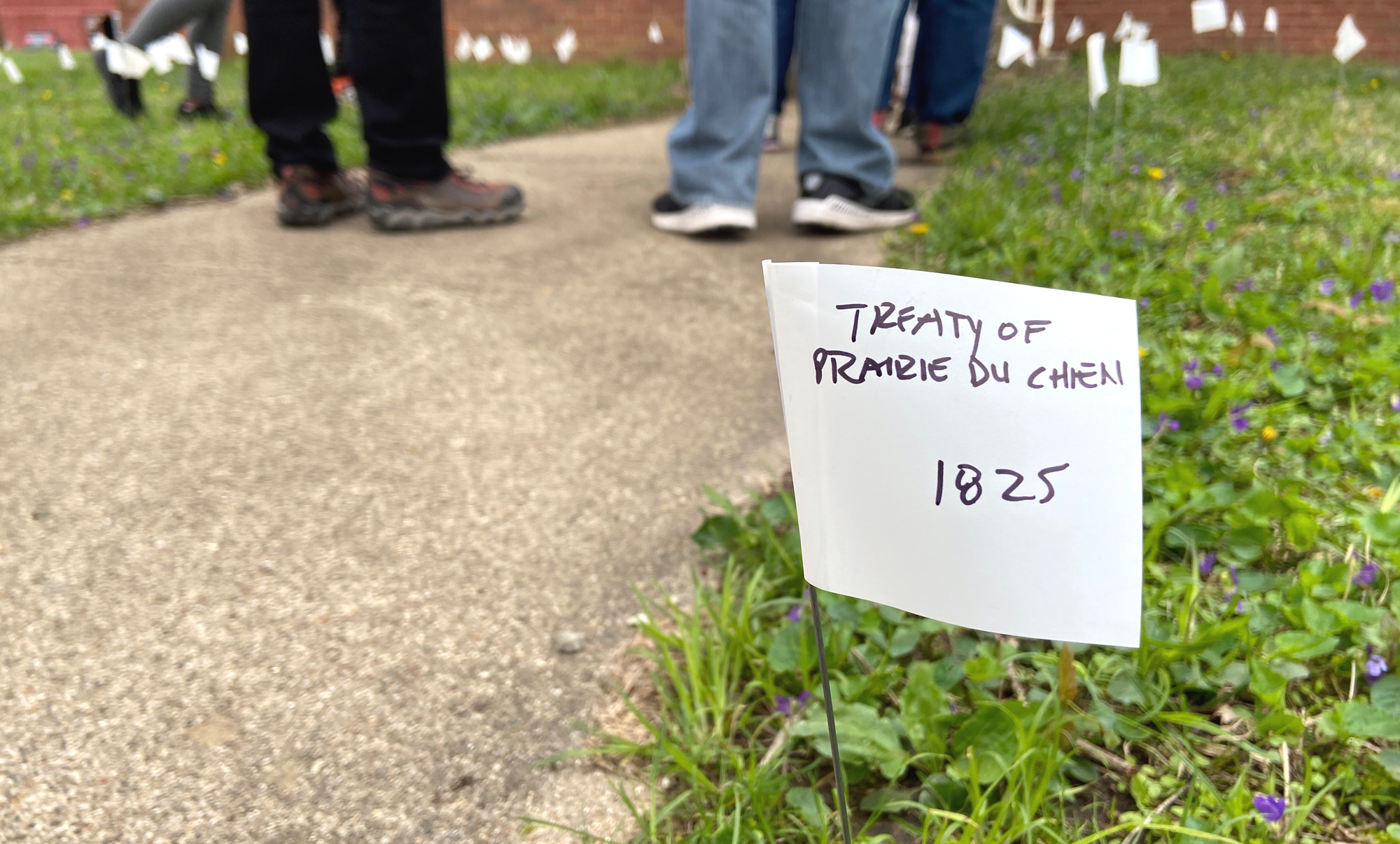

The event began with a procession from the Allerton Barn to the front yard of the residence. There we encountered 368 white flags in the yard, symbolic of the 368 treaties the United States brokered and subsequently broke with Indigenous populations. The state of Illinois made and broke seven treaties, and the names of those were written on seven flags.

Photo by Jessica Hammie.

Bright delivered a spoken word piece outside the house, as we stood among those flags:

It is unsettling

I

Black

Woman

Southerner

Still want to know

Where is my mule?

Am I it?

Where are my 40 acres?

Can they give me what ain’t theirs?

What claim do I have?

And yet

I lay claim

Place a stake in the ground

I Settle

But

What can grow on stolen land?

What has grown on stolen land?

Urbana singer and actor J’Lyn Hope sang a number of songs as we moved into and through the house. Her voice is beautiful; the effect in that space, while contemplating this particular material and history, was haunting.

During the rest of the performance and procession through the house, we learned that Monticello was founded in 1837, and in 1838 the Trail of Death passed through the area, the caravan camping on the shores of the Sangamon creek for two days in September. What’s the Trail of Death, you ask? It was the forced removal of Potawatomi people from Indiana to Kansas. I didn’t know about it, either. While they were camped in Monticello, children and adults died. The survivors had to get up the next day and continue on to Kansas. The tragedy and horror of the history of the Indian Removal Act is not an abstract idea in a textbook; it is here, in our extended community. The history lives in the land, even if these stories have been buried and forgotten.

Other components of the performance included a short screening of a documentary about the forced displacement of Indigenous people, and spoken retellings of accounts from Emma C. Piatt, who wrote a book about the area, the History of Piatt County (1883), as well as an 1888 article in the Chicago Tribune celebrating the annual “old settlers” reunion of wealthy white men who were instrumental in building Monticello as a town.

After the performance, Anderson-Cobb and Bright sat down with the audience for a question-and-answer session that, because of the small size of the crowd, felt more like a robust conversation at a medium-sized dinner party than a stuffy, artsy, or academic Q&A. One thing became clear among us, the audience, was that we knew the history in theory, but few of us were aware of the particulars to this area, like the Trail of Death.

It sparked a conversation about what is and isn’t widely known, and what and who and how we consider “our” history. For me, the performance and dialogue inspired more questions. Nearly all of us who attended currently live and work in, at, around, nearby to, or for Monticello and the University of Illinois. How many know about the Trail of Death that passed through this area, and the retracing of that path that happens every five years? What are the ways to share these stories, to hold and honor these narratives? To claim them as our history? Because they are our histories, whether we want to acknowledge them or not.

Photo by Jessica Hammie.

It’s projects like Anderson-Cobb’s and Bright’s that work to amplify truths, enact repentance, and subvert toxic culture that upholds images like the U of I’s racist former mascot. Though Anderson-Cobb and Bright are only in the beginnings of this project, it is ripe with possibility. There is so much to uncover and rediscover. I am very much looking forward to how they further develop the public-facing components of this project.

In the meantime, you can learn more about their research and share your own experiences of Allerton and Monticello at Allerton’s Greenhouse Slam on Wednesday, May 4th, 6 to 7:30 p.m.