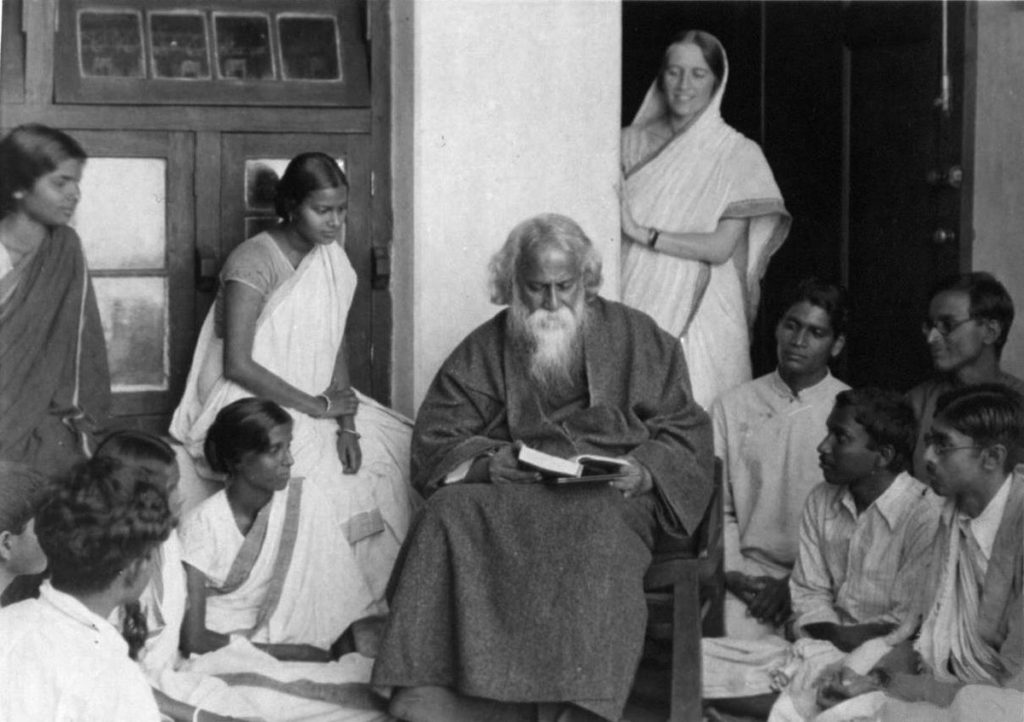

A few weeks ago, my friend Ragini brought to my attention that Rabindranath Tagore, the globally renown Bengali writer, activist, and cultural figure, had a strong link to Champaign-Urbana. During the academic year 1912–13, Tagore gave a series of lectures while visiting his son, who was a student at the University of Illinois at the time. This was the first time Tagore gave a lecture in the United States. While numerous articles about this visit have been preserved in the Urbana City Archives, it was his second visit, in 1916, that brought significant attention to the writer’s presence on campus. By this time, he’d already gained global acclaim as the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in literature. The venue for Tagore’s first series of lectures was none other than the Channing-Murray Foundation, at that time merely a quaint chapel.

Since 1989, the Channing-Murray Foundation, alongside the Tagore House Initiative, has put together the Tagore Festival. This year’s festival centered on an especially unique production of the writer’s play The Post Office. The director, George A. Miller Visiting Artist, Suman Mukhopadhyay, combined Tagore’s play with Vivek Narayan’s play Walking to the Sun. Tagore’s play is about a sickly young boy unable to leave his house. As such, he interacts with passersby through his window. At one point, the young boy, Amal, becomes enamored with the new post office, believing that he’ll receive a letter from the king.

This deceptively simple story of a sickly young boy on the precipice of death served as personal inspiration for the Polish-Jewish doctor Janusz Korczak. Pan Doktor, as he was known to those around him, ran an orphanage for Jewish children in Warsaw. Fiercely loyal to the children in his care, he stayed with them when they were all forced into the Warsaw Ghetto, and eventually refused sanctuary and joined the roughly 200 children when they were sent to Treblinka to die. Narayan’s play centers the doctor’s inner thoughts and his relationship with Tagore’s play. Historically, he had the children perform the play numerous times in the ghetto, seemingly preparing them for their impending deaths.

Mukhopadhyay’s production was, according to the director himself, still a work in progress. Rather than casting professional actors, he cast community members into various roles. Some actors played various roles. For example, the same actor portrayed a young version of Dr. Korczak, as well as the characters Gaffer and Fakir from Tagore’s play. Throughout the play, images were projected onto the stage, as well as clips from Andrzej Wajda’s 1990 film Korczak. I found that the supposed “roughness” of the production deepened the human elements of the play.

The earnestness of the amateur actors served as a reminder to bring my own earnestness and compassion to the forefront, as Mukhopadhyay’s production bridges two figures — Tagore the writer and Janusz the doctor — two men who centered the inner lives of children robbed of their childhoods. I especially liked the choice to have the same actor portray young Korczak as well as the Gaffer/Fakir. The latter builds a strong, personal relationship with Amal, fomenting the boy’s imagination. Meanwhile, Korczak himself fomented the creativity of the children in his care — even in the ghetto, by having them stage a production of this very play. Likewise, the choice to have both an older and a younger version of the doctor allowed us to see the old doctor reflect on his life at the end, knowing that death was imminent for them all.

When he found Tagore’s play, Korczak saw the children in his care reflected in Amal. He saw what Tagore seemed to see as well — that children, in their innocence, will laugh in the face of death. Sometimes death comes to children in the guise of a letter from an imaginary king, at other times it’s a train to Treblinka played off as a trip to the countryside. In framing Tagore’s play within the historical context of Korczak’s theatrical productions in the Warsaw Ghetto, we’re reminded of the power that art and literature have in times of despair, or how one story, like Amal’s, can become universal. And most importantly, we’re reminded of the universality of death and the power of childlike inventiveness to confront it.

I’m glad I had the opportunity to see this production, and to learn about Tagore’s ties to C-U. There’s something new to learn every day about this place, and its ties to the wider world. I hope the Tagore Festival continues for many years to come.