In brightest day, in blackest night,

No evil shall escape my sight!

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power, Green Lantern’s light!— Hal Jordan/many current Lanterns

Wikipedia

Like the DC Comics hero who inspired its title, In Blackest Shade, In Darkest Light evokes a multi-dimensional universe. It leverages a range of mediums, techniques, and critically-minded artistic voices against problematic constructs of power and privilege and Good vs. Evil. If I had to name curator Patrick Earl Hammie’s singular superpower it would be this: his incomparable ability to draw connections that remain invisible to others and to see the potential that lies beyond boundaries. In this exhibition, which you can (and should) see at Parkland’s Giertz Gallery through February 18th, as in the recent Black on Black on Black on Black, of which Hammie was one of four co-curators/artists, this superpower gives the exhibition and its companion programming, a resonance, and a potential reach, far beyond any gallery walls or closing date.

In Blackest Shade features artists Kumasi J. Barnett, William Downs, Kenyatta Forbes, Patrick Earl Hammie, Robert Pruitt, Stacey Robinson, and Charles Edward Williams and covers a range of techniques as widespread as the cities they work in. As Hammie writes in his curatorial statement these artists “draw from cultural aesthetics and philosophies of science and history to explore and improvise within set boundaries and beyond. Their work speculates toward un-fixing the physical, political, and social knowns and imagine otherwise how we will be and become.”

The late graphic designer and educator Milton Glaser famously wrote that drawing is thinking. The artists of In Blackest Shade take it further by using various drawing technologies to, as Hammie says, “speculate, recover and collect communal histories, manifesting stories of desired futures from the margins of imagination into the realities of the everyday.” And as the term drawing operates on multiple levels here, so does the notion of value. With a large portion of the work in black, white, and grayscale, value lies as much at the center of any discussion of technique as it does in consideration of the exhibition’s thematic inquiries.

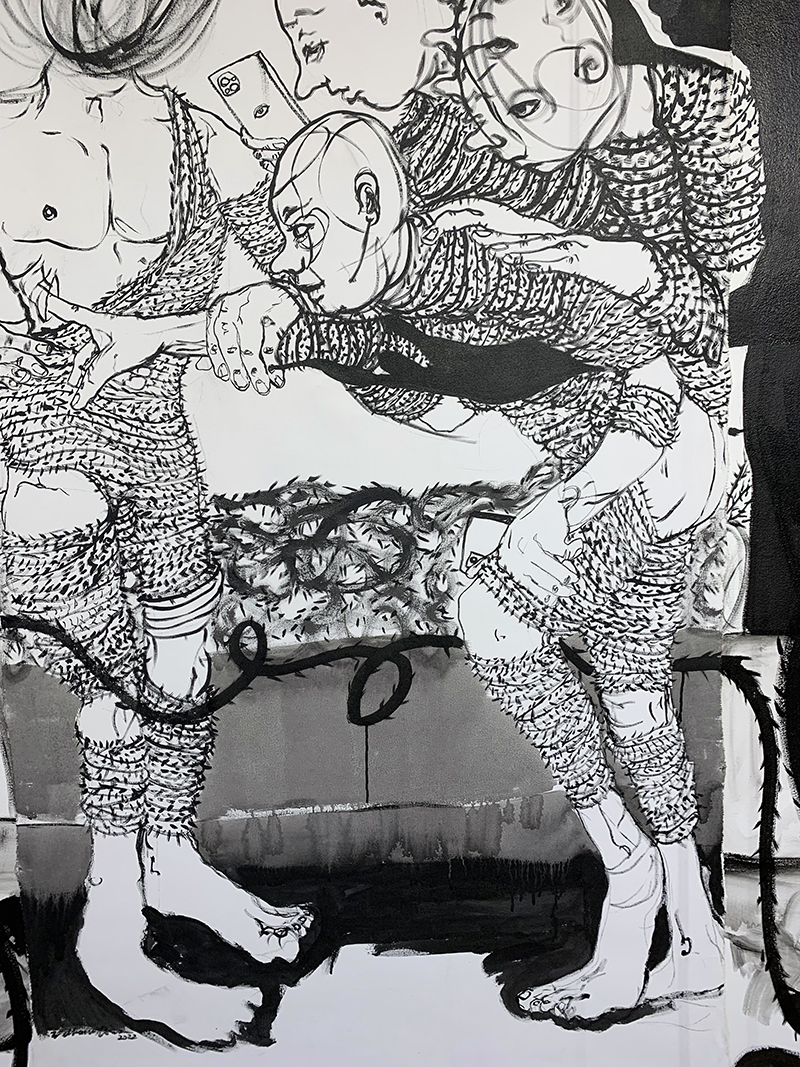

This detail from William Downs’ temporary installation drawing on canvas and paper exemplifies the artist’s intimate technique. Downs’ use of basic materials (ink wash and spray paint) evokes an immediacy and rawness that illustrates how his work processes loss and trauma. The layering of images on paper over those on canvas and drywall, seen below and in the featured image above, creates a dialogue between historical or public trauma and personal loss. The result is complicated, beautiful, at times messy, overwhelming, and brutally honest.

Kumasi J. Barnett’s series of one hundred hand-painted comic book covers, ten of which are included in this exhibit, subvert the traditional comic hero narrative. With each alteration of title and image, Barnett centers the problematic reality of justice, with classic supernatural villains replaced by the police.

The gallery’s back room features work by Hammie and Stacey Robinson, two of Black on Black on Black on Black‘s co-curators/artists. And while the work is clearly cut from the same cloth as the work shown at Krannert Art Museum, there are important differences. Seeing Hammie’s Rorschach-like images of Marietta, Georgia and Temple, Texas, lynching photograph silhouettes, and a singular piece from his Soul Train series in such close proximity only intensifies their impact and the complex dialogue between them. But it’s more than that. Having this work, which originated at the University of Illinois School of Art & Design — where Hammie is an associate professor and chair of studio arts — at a community college teaching gallery is a significant step towards finding what lies beyond our town’s academic and artistic boundaries.

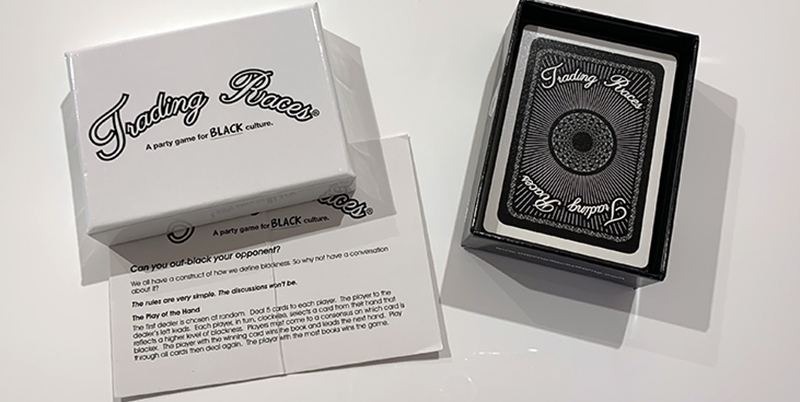

And like Black on Black on Black on Black, In Blackest Shade is designed for interaction. Finding Kenyatta Forbes’ Trading Races game atop a meeting table made me wish I hadn’t come alone. I consoled myself by imagining the groups of students that had toured the gallery and sat at this very table. I wondered what they thought and felt playing a game that warns, “The rules are simple. The discussion won’t be.” Note: If you’re an educator who teaches Black history, learn more about the free facilitator guide for teachers here.

And if, like me, you didn’t want your solo status to stop you from getting interactive, sit on one of the front gallery couches and browse the collection of books on Afrofuturism, and start to imagine. As you leave Giertz Gallery walk straight ahead into the lounge, where to your left you’ll find three more drawings by Robinson. Like the students seated in the lounge, the portrait of Grace Jones (see below) is a work in progress. It is dynamic and full of possibility.

Seeing the exhibition literally extend beyond the gallery space brought me much joy. Perhaps the real magic of In Blackest Shade, In Darkest Light is that it flips the script on the Green Lantern’s oath. The light it emits shines with enlightenment and hope, rather than surveillance and fear. And the real superpower at work is the community engagement efforts of its curator, artists, and Giertz Gallery director Lisa Costello.

Visiting the exhibition is only the beginning. Explore the work and its surrounding conversations at two upcoming free artist talks. At 6 p.m. on Thursday, January 26th, Kumasi J. Barnett will present an online lecture. Register here to receive the Zoom link. At 10:45 a.m. on Thursday, February 2nd, Stacey Robinson will present a talk at the Staerkel Planetarium as part of Parkland College’s Black History Month programming. At noon, attendees are invited to join Robinson for a “Chat and Chill” back in the Giertz Gallery. These promise to be significant discussions. Don’t miss these opportunities to be part of the interaction and bridge-building.

In Blackest Shade, In Darkest Light

Parkland College

Giertz Gallery

2400 W Bradley

Champaign

Through February 18, 2023

Get gallery hours here