I first encountered River Andres the poet at the 2021 Small Press Fest. Though we had known each other for years, this aspect of their life was new to me. But from that day forward I have continually been inspired and uplifted by the power of their voice and the visceral, kinetic energy of their words. And now you can be too.

At Small Press Fest, Andres was as vibrant and compelling as the chapbook they came to promote and sell. Their table was a site for conversation and bridge-building. I remember watching as illustrator Julio Gaytan created this portrait of Andres, shown below on the left.

Photo by Jeff Putney, them/them.

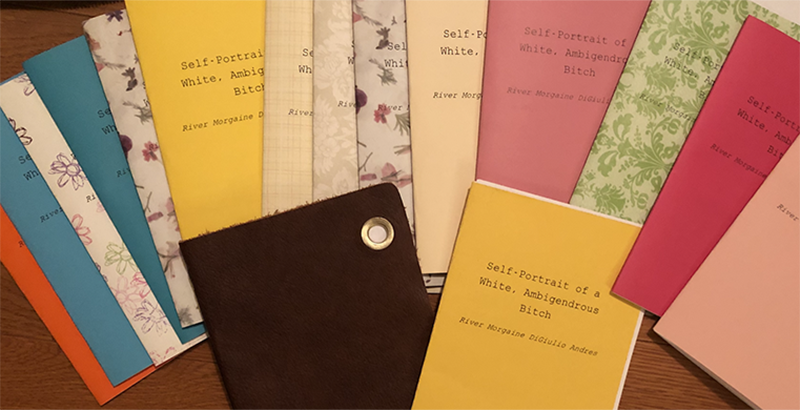

Soon, the wide swath of colorful, handmade chapbooks quickly began to disappear into the hands of festival goers who connected with Andres’ Self Portrait of a White, Ambigendrous Bitch. After spending time with my own copy, I knew I wanted to bring it to this space. But I also wanted to learn more about the poet and their process. Here is what I learned.

River Andres wrote their first poem as an elementary school assignment. It was about a polar bear and her cub and it was published in a book for the parents. Seeing their work in print clearly sparked something. Since the age of 13, Andres has been consistently writing poetry, often as a part of their daily journaling. Today, they often write on their smartphone, which allows for spontaneous composition.

Andres describes their approach as “free-style or flow-of-consciousness,” which aligns with the ryhthmic quality of their poems. Andres attributes this to their passion for music, particularly rap and hip hop, as well as their own experience writing songs. iAmong Andres’ favorite artists are Leikeli47 (pronounced La-Kay-Lee forty seven), Noname, Jamila Woods, Janelle Monae, and Tanya Tagaq, who Andres loves for her “amazing throat singing.”

Further talk of inspiration lead to a list of Andres’ favorite writers, which is topped by Octavia E. Butler, and also includes Toni Morrison, Sonya Renee Taylor, adrienne maree brown, Prentis Hemphill, poet Mahogany L Browne, Alexis Pauline Gumbs (Undrowned – a book which helped inspire my whale paintings), Miriam Kaba (We Do This Til We Free Us), debuting sci-fi writer Rebecca Roanhorse, and Ejeris Dixon. Andres also shared that Beyond Survival, co-editing by Dixon and Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasihna, provided significant help in their trauma healing process.

With a poet of Andres’ commitment to social justice, the line between inspiration and motivation blurs.

The thing which fuels my need to write poetry is a need to understand my own moment-to-moment emotional reality. I don’t think our western education system does a good job of teaching children how to have feelings (in fact, it teaches us how to not have them). My poetry often ties together what I perceive as seemingly disparate factors in life, which are actually deeply interconnected. I remember learning about intersectionality (a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw) when I was in college in 2009-2013, studying sociocultural and linguistic anthropology. That concept has influenced my life in so many ways. Intersectionality basically defies the Western perspective that we exist as individuals in a vacuum, every human a clean slate. We are all interconnected, and on a multitude of axes that intersect.

For Andres, the consumption and creation of poetry has been a personal and historical necessity. “Poetry has saved my life many times over,” they share. ” As I have existed in this trans, nonbinary soul in a body that is gendered by our society, and with access to our roots removed by white supremacist cisheteropatriarchy, I find sharing my poetry is a political move. I am writing myself into history. I am writing for myself, and I am sharing for everybody who has ever experienced the same feelings I have.”

Observing that “after a while that writing and later reading my own poetry helped settle something deep in my gut that nobody else’s writing (and nothing else) could do. I learned through the Combahee River Collective, a queer, Black Feminist organization from the 60’s and 70’s, that if we do not write ourselves into history, then we will be forgotten to history. We may be intentionally erased even if we write, but I know my writing heals me and I hope if I share it, it can help others to witness their own feelings. And so I feel that I must write.”

The more they have written, the more in touch they have become with their creative spirit. Andres describes the experience of “[receiving] downloads from my higher self right as I am going to bed. I have reached for my phone in the dark as I am drifting to sleep countless times to jot something down, two or three lines that I forget I even wrote by morning.” The first stanza (see blelow) of “Net” arrived in this very fashion. I often adore these lines, so I do my best to document them.

Net

I built a net today

the shape of you,

but when you’re fallingI built one yesterday

to catch myself,

but then you caught me

Poetry also provides Andres with a path for creating historical context. “Where I was forced into decontextualized realities, I write my poetry to pull the truth out of the white silenced past. My truth is worth witnessing, and I had to do a lot of healing, trauma-informed therapy, and time off of work to be able to realize and honor this. I have been privileged with the support of community, family and friends through much hardship over the last couple years, and I am eternally grateful for the gift of financial support to allow me space and time to heal.”

When I asked what motivated the decision to self-produce a chapbook Andres shared that they originally planned to pen an entire book. After compiling approximately 260 poems, research into current trends led to the more manageable “bite-sized” goal of a chapbook. They selected poems with the goal of presenting a range and variety of recent work; or as Andres describes, “some hard-hitting, some light and fluffy.” However, one poem dates back to a memory from Andres’ time training as a physician assistant. They were walking to training and “it was very, very early in the morning, and the sunrise was gorgeous, and I could smell the coffee, cigarettes and earth.”

Photo by River Andres.

As in-person readings make their return, I asked Andres if they envision reading their work live. While they feel the work does lend itself, they have some concerns about being able to prepare audiences for possible triggers. “My poetry covers a lot of deep, dark, hard shit, including childhood sexual abuse, white supremacy, white silence and slavery. Because of that, I am working to ensure that as I share my poetry I also offer sufficient content warnings so folks can choose to engage or not and know exactly what to expect. But it can be hard to do that without giving away some of the poem, or sometimes the most exciting turns, or the “conceit” at the center of the poem.” However, Andres is exploring the possibility of a podcast focused on reading and contextualizing their work.

While Andres is every inch the wise and confident poet and speaker, they are quick to share the vulnerability and self-doubt that comes with putting your work out there. “The process of writing the chapbook was a long one for me. I have had a lot of imposter syndrome to overcome. After I decided on the poems I wanted to try, I realized that I needed to learn how to edit them. I recall in high school (Uni High) I shared my poetry with a teacher and he shut me down so quick. Said I was being too explicit, I needed more ambiguity, more economy of words, fewer repeat words, etc. I was crushed. I decided then and there to never edit my poetry, to allow it the truth it deserved. Fast forward to 2021 and I was realizing there must be a good way to edit poetry. So I searched and I came across Faylita Hicks and her approach. I used it for all of my poems in the chapbook. It was tremendously helpful.

Andres also shared that the production process presenting a bit of a learning curve, as they experimented with formatting, stapling, and choses for unique covers, which were found at the IDEA Store.

Andres is in no way resting on the laurels of a chapbook completed and well received. Stay tuned for updates on a future art/poetry book inspired by Gathering River, their trauma healing project, as well as news on the future podcast that is currently dubbed “Assertive Bitch Technology.” To read more from River Andres, check out their Patreon site, where you can order a copy of Self Portrait of a White, Ambigendrous Bitch. Copies are also available at Art Coop in Lincoln Square Mall or by emailing the author at [email protected].