This past Sunday, the Japan House hosted its first offering in a series of workshops designed to bring the art of calligraphy, based on Chinese ideograms, to the public in Champaign-Urbana. The instructor for the class, University of Illinois Professor Emeritus Shozo Sato, is a master of several forms of Japanese art. As introduced by host Debbie Kim, Prof. Sato is extremely well-versed in Japanese Tea Ceremony, Kabuki theatre, Sumi-e (black ink painting), Ikebana (flower arrangement), “Okay, that’s enough; to introduce me it’s easier to say I do everything, it’s all related,” Sato politely and jovially interrupted, to the laughter of the class. And that was the tone for the entire day: students being taught by a gentle-spoken man, clearly a master of his art and himself, with good humor and an easy ability to connect to others.

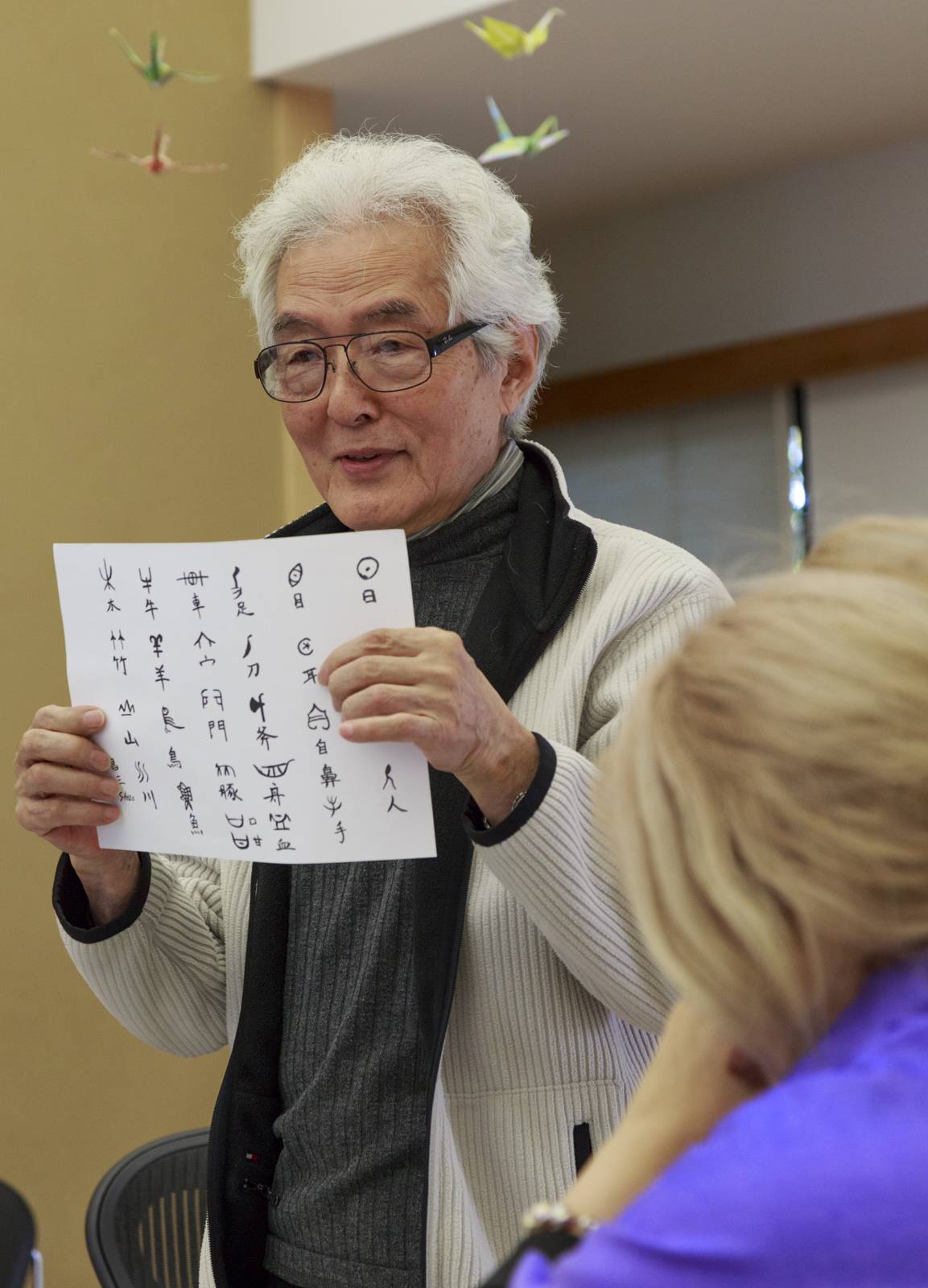

The instruction started off with Sato explaining that he had just returned from an out of state trip where he had become ill, apologizing for his lack of energy. His illness did not show, however, as he was both enthusiastic, precise, and commanding throughout the entire two-hour workshop. Beginning with a small history of calligraphy, he explained roots of how some symbols looked exactly like what they represented: an axe, an eye, a bird, and many others. After having the beginning and advanced students (those who had done calligraphy at least once before) move into separate groups, he called everyone up to surround him as he explained proper form and brush technique.

The art of calligraphy has as much to do with posture, breathing, and controlling your bodily energy as it does putting brush to paper. As Sato demonstrated the beginning figure the class would draw, it felt more like getting a miniature lesson in simply controlling one’s self. In the western world, where we write and draw with quick slashes of the pen, it easily looked like the brush crossed the paper without much care. However, as Sato demonstrated, you could see that each stroke came with minute, yet deliberate, changes in direction and pressure. It almost looked like a dance, and indeed Sato explained it this way. “Dancing and circular movement, physical and visual movement, it’s all the same.”

After the demonstration the class was released to try their own hand at the art. As they worked, many with looks of resolute concentration on their faces, Sato and another calligraphy instructor assisting him, Yoko Muroga, slowly made their way around the room to help each student. Even here, the difference between eastern and western teaching styles and how two people connected was apparent. Rather than simply show or tell each student what to do, Sato and Muroga gently put one hand on the student’s hand holding the brush and another on their shoulder, letting the student do the work while providing gentle guiding corrections. Every student was open and accepting of this, and after each bit of instruction there were nods of understanding and smiles of thanks.

Below, Yoko Muroga provides guidance to a student.

Below, Japan House staff member Debbie Kim offers a treat to a guest.

Partway through the class a treat of tea and thin wafer cookies filled with green tea paste (this tasted like an incredibly mild Oreo cookie) was offered, and participants enjoyed these before being called up again for another demonstration: how to make a dream. Sato began by demonstrating the basic components of the symbol, asking the group what each one looked like or what it might represent.

He then explained that with small changes in angle or shape the word could still have the same basic meaning, “dream”, but could be turned into a happy, sad, or angry dream. “You can express your feelings, and in this way express the meaning of a letter,” Sato explained, making quite animated expressions as he showed exactly this. “In this way you want to be careful when you write, because someone could possibly know you simply by looking at your art.”

With this the class was released to practice more, receiving more one-on-one guidance and instruction along the way. With about ten minutes left, pieces of rice paper were passed out along with a final instruction Sato: “Make your own fantastic dream.”

As the class concluded, participants held up their masterpieces and received praise from Sato for being such good students, and a thanks for coming to the instruction. He also asked what everyone’s experience was, and how they felt. Many commented on how they felt relaxed, and several stated that while they were frustrated at first they felt peace settle in partway through the lesson. There were lots of smiles, and everyone was clearly appreciative of the opportunity they had just had.

Below, “Which dream would you want?”

Clean-up, while normally done by the participants, was taken care of by Japan House staff, allowing the students time to chat with the instructors and compare works. After the guests had left, Sato invited me into the kitchen to sit so that he could rest and answer my questions. As we sat down, I felt quite privileged to be able to have some direct one-on-one time with a man who had clearly experienced much of both eastern and western culture in his long lifetime.

Smile Politely: Could you tell me why it is that you teach people in these arts, such as calligraphy and Kabuki? What drives you to do what you do?

Sato: I grew up during World War II, and joined my father in Hiroshima looking for family after the bomb. There was destruction everywhere, and I realized that war is a cultural clash because people do not know each other. I wanted to inform the western world how the Japanese people feel and think, and to create a better people understanding.

SP: What makes art such a good way to connect different people?

Sato: The general public is interested in things like culture and food; they’re not interested in business and politics. Art, common art, has its own language. Through art we’re trying to reach out and inform others of how we think and feel, to reach out to the westerner. And Japanese art is not realism, it’s always minimalism or exaggeration.

SP: I’ve noticed that; everything in Japanese arts that I have seen has either been almost over the top or very subtle. Why is that?

Sato: Art should give joy or hope; why repeat or reproduce the difficulty of reality? You want to provide either enrichment or simplification, bringing people closer, smiling and sharing joy or laughter.

SP: What are some of the challenges you’ve faced in bringing your vision to Champaign-Urbana?

Sato: Because Japan had lost the war, anything coming from Japan was seen as being less. People would say, “Japanese are bottom of the pot, what could you possibly teach us?” When I first came to the University in 1964, many of my colleagues didn’t understand why I was here, and I was asked if I would rather be in New York where many other Japanese artists were. I thought about that, but realized that my life value was more important in Champaign-Urbana than in New York. So I had to convince many of my colleagues of my purpose for being here, which took about ten years.

SP: How have you seen culture change over your lifetime?

Sato: We keep making the same mistakes. Each generation lives and dies in its own period, so it repeats the past. People create, or do things for others, for their own pleasure.

SP: What can we do to improve things?

Sato: I’d say let’s try to make it, become part of each other’s life patterns. Take the tea ceremony, for example. It’s not about what the guest needs that I can provide, but what can I offer to them that they may take? Their happy face is what should make your happy face; we should create and do things for their pleasure. Each human has a place to make the world better, but some people close their eyes to this effort. Each person should open up their mind to share, doing as much as they can. It’s a duty.

Thank you again to Professor Sato and Japan House; this was truly a wonderful experience. If you missed this workshop but are still interested in a chance to learn, additional workshops will be held on October 25th and November 1st. The cost is $15 for students, $20 for Tomonaki members, and $25 for the general public. For more information, please visit the Japan House Website or call 217-244-9934.