The Sankofa RoboBuilders did not win the FIRST Lego League Qualifier competition held on the University of Illinois campus back in December. But that’s only if you have a very strict definition of “winning.”

When translated literally, sankofa, a word from the Akan people in Ghana, means “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.” Stated more simply, it means “go back and get it.” More broadly, it “symbolizes the Akan people’s quest for knowledge among the Akan with the implication that the quest is based on critical examination, and intelligent and patient investigation.”

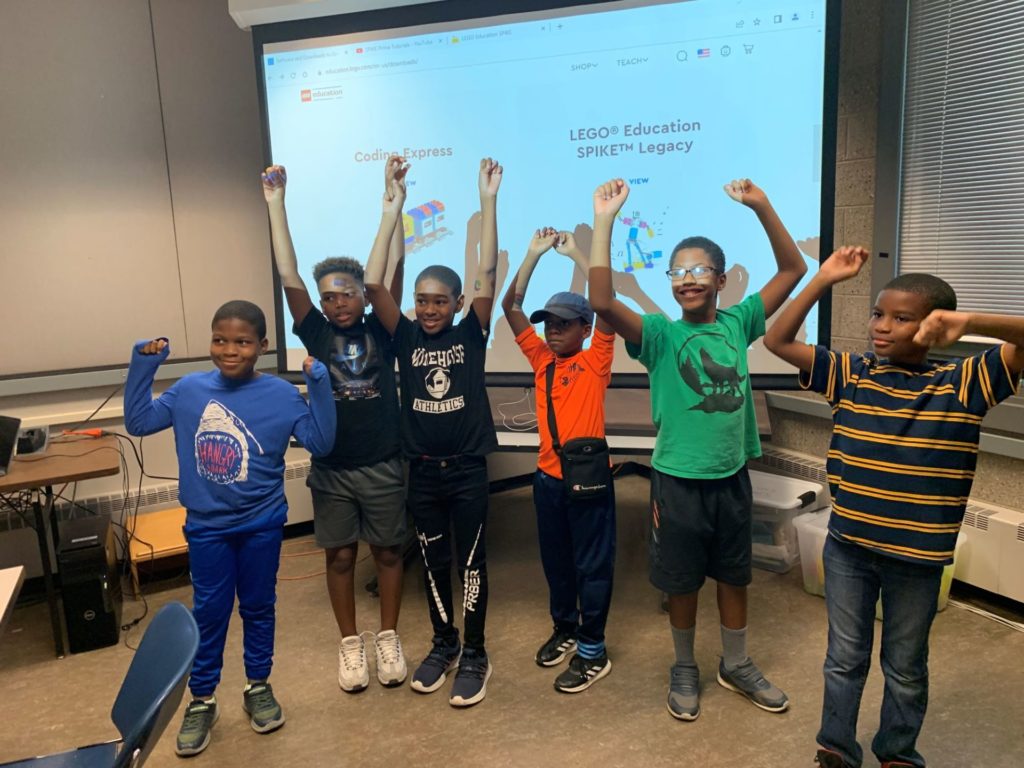

The Sankofa RoboBuilders may not have come home with any awards, but after I spoke to the team of six nine and ten-year-old African American boys and their parents, it was pretty clear their quest for knowledge resulted in a lot of rewards that don’t necessarily show up on a judge’s scoring sheet.

Prior to meeting with the group, I got a little background from Deneca Avant, mom to team member Andre, about how they came together. She shared that “It began as a group of parents connecting with others within the C-U community, who were looking to establish or expand their FIRST Lego League Robotics Teams.” For those who aren’t familiar, FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) Lego League (FLL) is a global program that “introduces science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) to children ages 4-16 through fun, exciting hands-on learning.”

As interested families began to split into teams, Avant was part of a group of parents with kids left on the outskirts of those already forming teams. They looked at each other and said “okay, we can do this!” Fellow parent Imani Anwisye Mashele, mom to team member Manqoba, said, “Deneca helped light the spark.”

Coaching this new team became an all-hands-on-deck sort of endeavor, with Mashele stepping into the role of “official” coach. She described herself as a coordinator and deadline keeper, but emphasized that each parent played a role in the success of the team, whether it was writing grants, bringing food, securing meeting space, or making sure each child had their own robot to work with. Reggae and Moyenda Anwisye, parents to team member Akinyele, were the FIRST Lego League veterans of the group, with three older children having already participated, so they brought institutional knowledge of the guiding principles of the leagues. As Mashele described, it was like bringing together “your best team” to take on a new challenge.

And overwhelmingly, a challenge is what this group of committed parents was seeking for their sons. Pointing to the low percentage of African American men in STEM (Black workers remain underrepresented in STEM fields), Avant said “the Sankofa RoboBuilders’ parents were adamant about cultivating the team’s passion.” Andrew Martin, Jr., dad to team member Andrew, echoed this desire to encourage their kids’ interest in STEM. “This place has so much to offer when it comes to engineering. They want to reach out to people of color, so let’s reach our hands back out.”

Some of the kids came in with this passion for Lego Robotics already, and their parents were looking for a way to continue to build on their knowledge. Others saw this as a way to nudge their children out of their comfort zones. This was the case for Martin, Jr. In describing his son Andrew, “a lot of the skills here were not his strong suit. He’s had some academic challenges, but he’s the hardest working kid I know.”

Reggae Anwisye was looking to encourage Akinyele to explore these sorts of tech activities. Even though he was raised around it, he wasn’t as naturally inclined as his older siblings. “It was important to us to find a team where could participate with people that he knew and would be comfortable around,” she explained. “It fueled Akinyele’s interest in these technical areas. He was willing to stay up late, he was willing to go above and beyond, he was willing to work on things that don’t normally interest him, because he knew the group needed his contributions.”

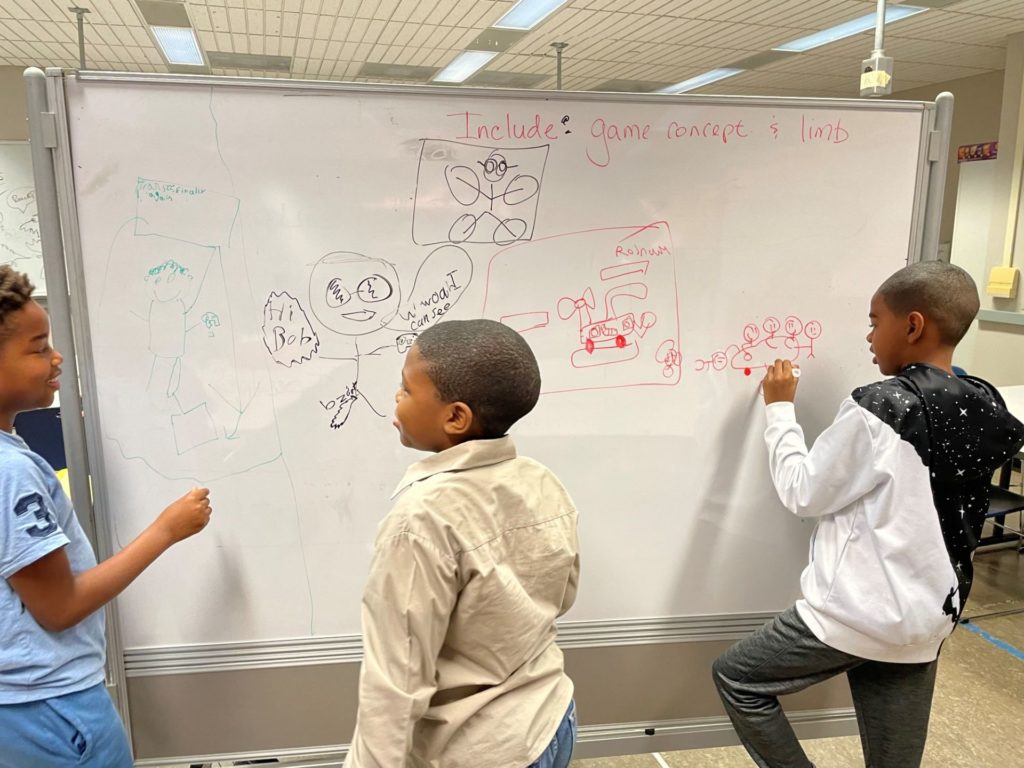

Once the group was formed, they met nearly every week for months to begin preparing for their competition this past December. There were three main components that they needed to work on: An innovation project, building and programming a robot, and building and completing a variety of challenge missions with that robot.

The first task was coming up with an idea for their innovation project, described this way on the FLL website:

FIRST LEGO League Challenge teams will use critical thinking and innovation to inspire others to learn and be entertained. Students will collaborate on their ideas and must consider efficient design for their user, possible barriers to implementation, document the evaluation of their invention, and validate their design with professionals working in STEM.

Andre described how the team went about coming up with an idea: “We all wrote down things we wanted to do, and all of them wrote soccer and I wrote football, so we decided to focus on sports. Then for our innovation project we decided to try to make virtual reality sports for people with disabilities.” Manqoba elaborated, “It was for people with most disabilities [including] blindness, deafness, quadriplegia.”

Their innovation, “Roboball for All,” would allow someone with a disability to use augmented reality to participate in a particular sport. They used soccer as an example. Andre offered more details: “People with a broken leg or a broken arm can play soccer without getting hurt. If you are blind, then if you’re close to the ball it would make a beeping noise. If you’re deaf, then when you get close to the ball it would turn a different color.”

In addition to working on this innovation project, they needed to build a robot using a specified kit, build missions for the robot to do, then code the robot to perform those missions. I gathered from the boys that this part was the most challenging. Andrew thought building the robot was the hardest part, and team member Josiah agreed. “Once the robot just kept tilting. We couldn’t find the right arm that we needed.”

Other team members spoke about the coding piece being the most challenging, including Rohan and Akinyele. Akinyele said “The part I found a little difficult was coding the robot to deal with the missions. Sometimes our codes would be close but not quite.” He went on to describe what those missions were like. “We each took turns. We went home with a mission and had to code it. The one I had, the robot had to go forward, turn a spinner, turn the lights on, and turn the speakers on.”

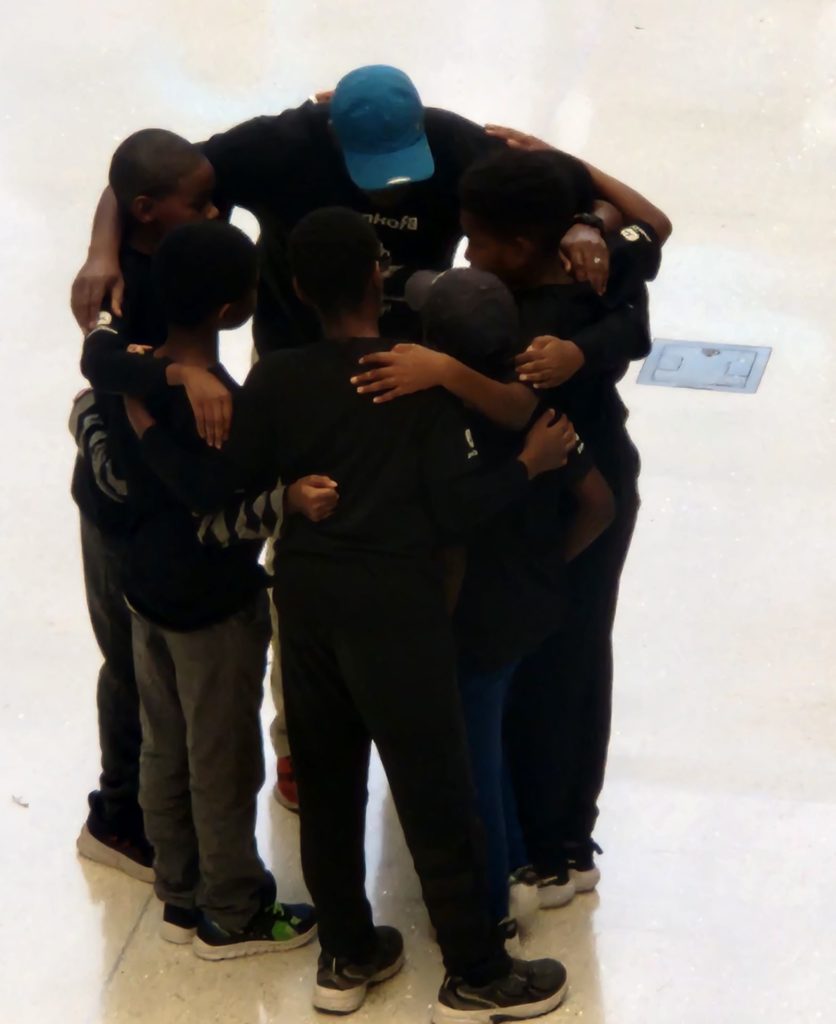

All of this hard work and preparation led up to the competition, and their feelings were all over the place that day: tense, nervous, happy, stressed, scared, and tired (it was a long day and a late night). Rohan summed up his feelings like this: “When I walked in the room and I saw a lot of players I said, ‘oh boy.’”

Oh boy is right. Andrew said that they were one of the youngest groups there. This was also the first opportunity they had to see what all the other groups had been working on. They certainly came into this competition as underdogs, and indeed, they left without a “win.” But, for the boys and their parents, there was a lot to celebrate. Akinyele had an insight about their first competition.

“For some reason, after the final outcome came, I felt a little happy. If we do this again, I think we know that we learned from our mistakes. I read this in a book once, and it reminded me of our situation. The quote was ‘Learn from our mistakes moving forward.’”

Their parents saw so much growth in their kids throughout this process. Remember how Andrew doesn’t always have the easiest time academically? His dad said “For him to accomplish [this challenge] was such a moment of joy for me and my wife. It raised his confidence level. Even his teacher has noticed.”

Dwight Thompson, dad to Rohan, saw him become more adept at public speaking. “My son does not like to talk in public. But when it came down to the presentation, they rocked it. I was so proud of him that he came out of his shell.”

Rohan’s mom, Antonia Thompson, said “it was character building and it was fellowship.” Mashele saw how they were able to build a recognition of each other’s strengths. “Everybody had something to offer…Even if someone had a challenge in a certain area, they would shine in another area”

This sort of skill-building was not by accident. It’s woven into the core values of First Lego League. They’ve even trademarked two terms: Coopertition, and Gracious Professionalism. The former involves “promoting unqualified kindness and respect in the face of intense competition.” Teams will earn extra points if they can work together with opposing teams to accomplish missions. Reggae Anwisye shared a little about the latter: “It created a space for us to work with our children on some good personal habits: Allowing people to speak without interrupting, holding your composure even when you disagree or finding a way to disagree peaceably. Those were skills and experiences that we were glad for our children to experience together, and have a safe space to not do so great at it the first time.”

Of course, the boys also had an entire team of parents and mentors encouraging, supporting, and guiding them through the process.

What’s next for the Sankofa Robobuilders? When I met with them it’s the first time they’d gathered since their competition, but it seems like the drive is there to see what they can accomplish in a second go-around, armed with new ideas, more confidence, and maybe a little bit of a desire to bring home some hardware. Moyenda Anwisye saw how “they were able to walk through that process, cue each other, and just go with the flow. They stood up there and did what they needed to do. I’d like to see them do it again and take it to the next level.”

Sankofa “encourages learning from the past to inform the future, reaching back to move forward, and lifting as we climb.” It seems the RoboBuilders are poised to do just that.