In his brand new book Food Power Politics, Dr. Bobby J. Smith II builds on the stories and legacies of Mississippi activists and researchers to tell more of the food injustice story. With a background in agricultural economics and Black justice at the forefront of his interdisciplinary research, Dr. Smith uses food power politics as a framework to combine both the history of how food was used as a weapon against Black people and also how they fought back against the injustices. He highlights how Black communities in the Mississippi Delta created reliable trans-local food networks, grocery stores that didn’t look like grocery stores, and secure food systems. Further, the book connects the stories of the past with the farming that Black youth are doing today on the very same land — literally the same street — as the historical Mississippi cooperative farm in the 1960s.

Weaving together interviews with individuals, records from historical archives, transcribed testimonies of Black activists, and more, Dr. Smith’s new book adds four chapters to the scholarly texts about the American civil rights movement. Unlike the other research about civil rights in Mississippi, Dr. Smith’s Food Power Politics uniquely centers Black justice, highlighting the work of Black farmers in the past and empowering Black farmers of today.

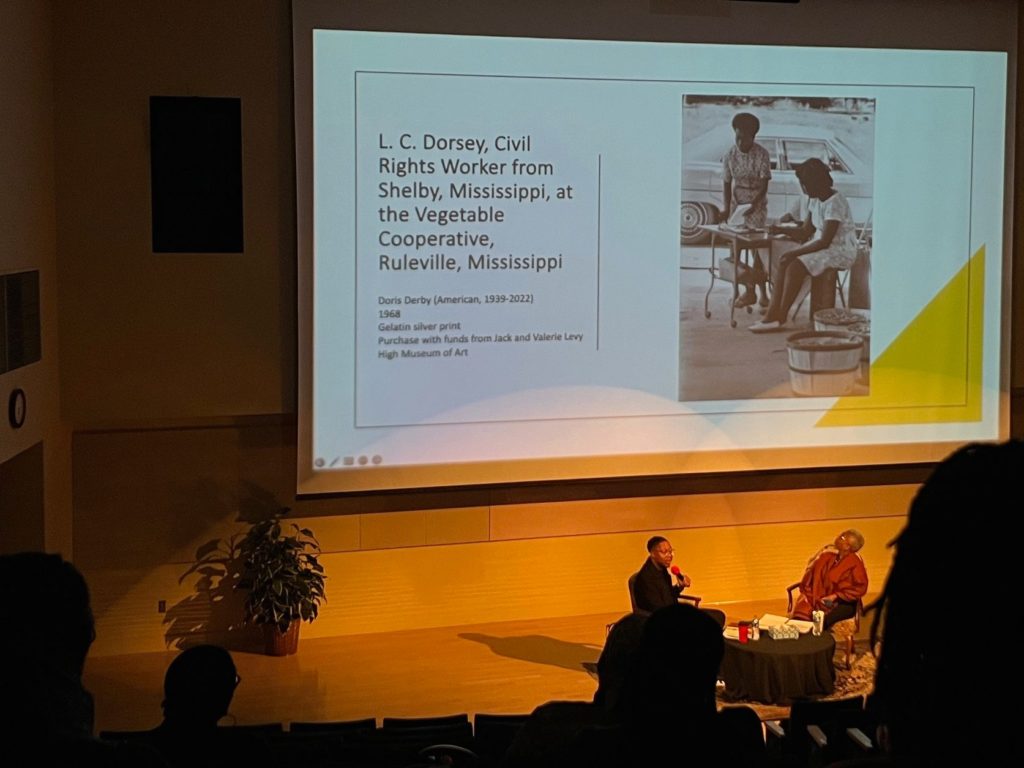

Since he’s an Assistant Professor of African American Studies at the University of Illinois and based here in Champaign-Urbana, I reached out to see if he wanted to talk about food and his new book with me. He said yes, and we met up at the Espresso Royale in Urbana. Later that week, I attended the Food As Power event where he discussed Food Power Politics in casual conversation with Spurlock’s Monica M. Scott, which is where these photos are from.

In this exclusive interview with Smile Politely, Dr. Smith shares more about his new book, how his research is different, and why the term food desert doesn’t really capture the whole story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: Let’s start at the beginning. When did you first start writing about food?

Dr. Bobby J. Smith II: I’ve been publishing about food since 2013. My first article was about farm-to-hospital programs. When I was in graduate school, I studied factors that influenced the hospital’s decision to adopt a farm-to-hospital program. It’s a part of the farm institution, farm-to-school programs, but I was interested in understanding what kind of factors hospitals need to start procuring locally produced foods to include both inpatient meals but also in their food service. That was my first time actually publishing around local foods.

SP: What drew you to writing about food, out of all the things to write about?

Smith: My entry point actually is in agriculture, so my entry point into studying food systems and production has always been through an agricultural lens. When I was going into my junior year in high school, I did a summer program for agricultural sciences, the Research Extension Apprenticeship Program for Agricultural Sciences (REAP). Illinois has a version of it, but the original program started in my school, Prairie View A&M University in Texas, and Prairie View is one of the first [institutions] to get the model right.

SP: What makes the model right?

Smith: You’re able to see that you’re able to recruit a max. I think when the maximum was 30 students, it was a rigorous application process. You had to get it notarized. You had to get reference letters. Then you sent it in, and then they review it, and then they send out acceptance letters. Then you go for a summer program of six weeks and study agricultural sciences. You get a stipend, free housing, free meals — and Prairie View is a historically Black university, and so this is designed to get more Black youth involved in agricultural sciences.

I started that program in 2005 and did it in 2006 as well, both summers back to back. And that’s what got me involved into the academic side of agricultural and food research.

But I come from generations of Black farmers and Black sharecroppers in the South. Land agriculture, food production has been a part of my life, at least as part of my family’s legacy, at least since the early 1900s. My mother’s from rural North Carolina. So every summer I would be sent back to her hometown to stay with my grandmother and family members. My great grandfather, who lived to be 101, he actually still lived out most of his life rural, and I spent many of my summers there. That’s how I got connected to family legacy.

SP: What brought you to University of Illinois? Because you got your PhD at Cornell, you probably had some options.

Smith: In 2017, I got a summer fellowship to conduct research on my dissertation project. Food Power Politics was born out of ideas from my dissertation. I got this really nice fellowship, and it was a very competitive fellowship because it was for junior scholars, early career scholars, and graduate students. I was just a graduate student. While I was there over the summer, I met Dr. Ronald Bailey, who is a former head of my [U of I] department. Dr. Bailey was actually on the selection committee, and I never met him before. And he attended my talk, and he was like, I’m very fascinated by your work.

It really did change the trajectory of my project, getting that fellowship. I’m back to Cornell in August and started writing the dissertation. I was thinking about: do I want to do a postdoc? Where do I want to live? Illinois was not on my radar at all. [In] December 2017, and I got a phone call from Dr. Bailey, and he was saying, “Hey, this Dr. Bailey. Do you have any plans next year? Because we’re actually getting ready to roll out a chance for a postdoc in our department. And I think your work is really, really innovative. It’s path-breaking. It’s ground-breaking, and you should consider applying here.”

So I went back to my community, and we’re like, if they are interested in me applying, I should apply. I received the fellowship, and it was the best fit for me because this is a big ag school. It was good for me to be in a place where I could be in African-American Studies but still have the ag people here.

SP: You just wrote a book. Is this your first book?

Smith: This is my first book. It’s a culmination of a shift for me, honestly, because my earlier research was around particularly local food systems and agricultural systems but not from a racial lens. Then around 2013, 2014, I met a Black farmer in Ithaca, New York.

He was the only Black farmer there at the time, and he told me about this idea of food justice. And I never heard of food justice before. I knew a little bit about it, but I never really fully considered food justice as a site of research. So I learned more about it, and I, in a way, self-taught myself the literature. There weren’t classes about food justice at the time. There weren’t any people weren’t getting PhDs in food justice. I don’t have a PhD in food justice. Mine is in Development Sociology, so for me, learning about food justice made me rethink the research I was already doing. I was rooted in ag systems foods, and so I knew all that research, so when I came to the justice conversation, I came into it from a different angle. For me, it was: How do I bring justice into the conversation? Which makes me different than a lot of people who do this kind of work?

[The farmer’s name is] Rafael Aponte. We started organizing together around doers. I went to his farm, started learning about some of the work he was doing. One of the book chapters I wrote was about the work he does on his farm. That’s how I came into it, from personal experience. Family history, my mother and my father did not go into agriculture because the way they grew up in it. Growing up in those times in the 50s and 60s, the relationship between Black people and agriculture was not always framed as a positive. It was framed as oppressive. It was framed as hard work. So they were trying their best to get away from the land. And then when I come about, I’m kind of returning to the land in a sense but from a different vantage point.

SP: Food Power Politics is part of a publishing series with UNC. Is that connection because of your family’s North Carolina roots or is that totally unrelated?

Smith: Unrelated, and it’s interesting because when I got in UNC press, my family, we were like, wow. The land was in my family for many, many years before they sold it. It’s probably about an hour and 20 minutes from Chapel Hill.

Food Power Politics is the inaugural book of that Black Food Justice series. And the series was created by Dr. Ashanté M. Reese and Dr. Hannah Garth, both anthropologists, who studied food justice and Black food. The series is designed to usher in a new generation of research that explicitly puts justice at the center of Black food, farm, and ag systems. So instead of just studying Black ag systems just to study them, this is actually putting justice at the forefront. What does it mean to write towards liberation or write towards freedom? We’re writing this. We’re conducting research, but we’re conducting research because we want to actually contribute to the liberation of people who are marginalized. It’s a different kind of approach than just writing in general about ag and food. We’re writing with a different purpose.

We’re contributing to the literature, but we also want our research to have an on-the-ground effect. We want everyday people who are engaging in these struggles to find help or some type of help or some type of lessons or models from the books that we do.

My book is the first book in this new series that just started in August. There’s another that came out in October; it’s all online.

SP: I like how you connect the history with what Black youth are doing now. I feel like I hadn’t really connected those myself until I read your book.

Smith: It matters how we tell the stories of the past, and it matters what stories we tell. People tend to tell or rehearse the same story over and over and over again. While it’s important for us to rehearse important stories over and over again, it’s also important for us to go back to excavate new stories.

For example, when we think about the way the civil rights movement is studied more broadly, it’s a study through the lens of voting rights. Education, segregation, public accommodations, so it speaks to present day issues around voter suppression, around segregation in schools, around public accommodation issues.

If you study the movement more broadly, it connects directly to those issues. But what does it mean to rewrite the history of the civil rights movement and make it directly connect to food access, food security, food issues? That’s what my book is doing because the civil rights movement is a movement, as we broadly know, it does not speak directly to food issues. The movement can inform organizing strategies. It can inform how people gather together to organize around issues. But what does it mean to take a particular issue and show how the movement also speaks to this?

It’s one of the most important social movements in American history, but now my work is providing us a way to speak directly to a big issue today, in a big issue that’s more in focus. It was a big issue in the past. Folks have been hungry, food insecure for years. But now the nation — somewhat since the pandemic hit — is really trying to understand how people are getting food.

But we’ve yet to take food seriously. And how do we get food? How do we get food to people in a sustainable way? But consistently. Not just these one-offs. Because the pandemic hit, we need to get them bread; we need to get them food boxes.

People need food for the rest of their lives. How do we create systems that enable them to feed themselves forever?

SP: Your research is specific to Mississippi. Before this, I did some reading and learned that Mississippi was the epicenter of the civil rights movement. I was a good student; I paid attention, but I didn’t get that out of what was taught to me in public school.

Smith: Me too. I thought I knew the civil rights story, too, but the story we know is incomplete.To your point about Mississippi, the reason why people tend to not talk about Mississippi or even places in the American South in general is because these civil rights movements take place in largely rural areas. In public schools, we learned about it in Atlanta, in Birmingham, in Chicago. It’s Jackson, Mississippi. It’s these urban epicenters of civil rights activism.

But the movement at large was actually in rural areas because rural people were the ones that were directly in confrontation with the white political and economic power structures. Because their lives were more shaped by that. If you were living in an urban area, thinking about Martin Luther King, Jr., living in a middle class Black neighborhood in Atlanta, his struggles were different than someone who lived on a plantation.

And plantation culture and plantation life was a big experience for Black people, particularly in the rural South. The movements went into the rural south to face these issues. They only went there to make a point. And then once the improvements were made, many of them began to abandon more of the bigger figures. So when we talk about civil rights movement and the story, we focus on big figures.

If we stay focused on the rural areas, as the big figures leave, there are local figures that emerge and become important people. But they’re not on the front page of newspapers. They’re not at the center of stories. When you go to the areas and talk about these people, these people made a major impact in their local area. That’s what some scholars argue: That the civil rights movement is a movement of movements.

SP: I kept reading that there were so many groups that were working together, building on the work of each other. Names I had never heard before, but Operation Breadbasket, grocer companies, Greenwood Food Blockade.

Smith: In the book — I don’t really get into this a lot — but a lot of the earlier activism in the 60s was student activism, younger people organizing. It makes sense for younger people to do the work today.

The activists weren’t taking up farming and food. They were leading the charge. I was doing an interview with someone in Mississippi; people thought the civil rights movement was supposed to take people out of the rural. I know one scholar says the civil rights movement was characterized as liberation from the fields, not recognizing that agrarian life is at the center of the Black American experience. It’s because of how we’ve reconfigured agrarian life is what’s made it so oppressive.

If we think about the long Black agricultural experience, it’s not all oppressive. There are these pockets of liberation and freedom that we don’t pay attention to and that we don’t talk about. So when you hear about Black farmers today, all you hear about is land loss and dispossession, lack of credit, lack of capital to grow food and do those kind of things. But in actuality, that’s only one part of the story, and the work that I’m interested in doing is just adding another point. I’m not saying what people did wrong. They weren’t wrong. They provide an entry point, and then it’s our jobs as generations coming after them to contribute more and more to the story.

It’s always about Black people’s relationship to agriculture. People no longer — or Black people in particular — see agriculture as a thing of the past, and that it’s something that we should be running from and not running to. That also plays a role in the lack of Black farmers. While dispossession does play a major role, it’s not that there’s a new generation or a big generation of Black people running back to the farm in numbers. There might be some people who are growing gardens, so they’re farming, but I don’t know any local commercial farms that are Black-owned. I know people who are growing food at their home. People are farming non-commercially.

SP: When you wrote your book, you interviewed people. Who was the coolest to talk to?

Smith: I think the coolest interviews were with the youth, between the ages of 15 to 18 years old. Those were the coolest interviews because I talked to them about how they envision the future.

I write in chapter four about this idea of care. And for them, self-care is care for self and also care for community. It’s different because when we’re thinking about self-care and the more popular discourse, it’s about being selfish. For them, self-care is caring for self and caring for community because we need each other. It was very, very encouraging to see how they saw food as an entry point, but also they saw food as an energy point.

In chapter four, I provided a quote from one of the youth where he talks about how he wants to see his community do better, be better because he saw so many of his community members die from lack of access to nutritious foods. He wants to see his community thrive through actually having the kind of food that they need to develop their body, so they don’t have to die. It’s like, “Oh, these people just don’t want to eat right. They just don’t have good eating habits.” But in actuality, they have no choice.

SP: It’s a food desert.

Smith: They have to eat whatever is available and what food is there. That’s the reason why people are beginning to think that the whole idea of food deserts might not actually capture what’s actually happening on the ground. Going a little deeper, some people are using language like food apartheid. They’re arguing that there’s like a system of segregation that segregates some people to nutritious food and some people to non-nutritious. Food deserts, while they are helpful in identifying the lack, they don’t provide a reason for lack, and they don’t capture people fighting against the lack.

Those of us who don’t understand how people can’t get food, it’s because we don’t live in those kinds of conditions. But there are millions of Americans and households that live in those conditions every single day. The way they get food shapes their entire lives, shapes their work schedules; it shapes their bus schedules. It shapes the kind of food they can pick up, given transportation or not.

Do they have a kitchen? Do they have a stove? Do they have a refrigerator? And we’re saying, “Oh, everyone just eat fresh produce. Eat fresh vegetables!” Well, what if they don’t have anywhere to store it? It’s going to go bad. So these are the kind of questions that I raised in my classes because my students tend not to — [and] us as a nation — we don’t take seriously these kinds of issues.

SP: We are not thinking this deep.

Smith: Yeah. It shows you how food really is a critical site of analysis that helps not only help us understand people’s experiences with food, but those experiences also reconfigure how we understand what food even is.

SP: Obviously, I’m not as versed in all of this as you, but is this kind of groundbreaking? Your thoughts on food is a weapon? It is, right?

Smith: It is a novel lens. Honestly, I would say my book is probably the first to explicitly give this idea book-length treatment. People have mentioned the ways in which food has been weaponized. In the introduction of my book, I talk about how in enslaved narratives, they talk about food being used as a weapon. Civil rights activists talk about it, too, but it’s never been taken up in a book length. What I do differently is that not only do I show that food is being used as a weapon against these communities, I also show how these communities fight back. That’s what’s missing from the narrative. What the narrative is: Food is a weapon against Black people, or Black people using food to address inequalities, but they’re never put together. And when I wrote this book, I wanted to intentionally not only provide but also point out there are vicious people who will starve people just to ensure they get a vote.

The same people who are being starved are not sitting by and passively letting themselves be marginalized. They’re growing food, whether it’s hidden behind houses. They’re producing cooperatives. They’re producing a network of grocery stores that don’t look like grocery stores, and they’re connecting them with a network. I talk about a network of grocery stores built on a cooperative, and they have a food cold storage unit in a nearby city, but they also have food drop offs. If you don’t have a refrigerator, we’ll store your meat in a locker, and then you just call us or let us know you need it and then we bring it to your actual house.

It was a local Black food economy that really that was rooted in the lives of activists, and they saw it as a continuation of the movement. In fact, I talked about it in chapter three that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other people saw the next phase of the civil rights movement addressing food economics and poverty. The first phase was all voting rights. There was no way around it because we need to vote. Hopefully, we vote the right people in and they make the right decisions.

But the next phase was economics and poverty and food. Of course Dr. King died before a national platform or a permanent platform could be made. In areas like Mississippi, these people were actually doing this work, and they created systems. They fed over 500 families. Thousands of people in a very small area who are basically building a new life on the ruins of plantations, because in the 60s plantations are growing and labor is shrinking because of technology, herbicides, pesticides, machineries.

What do people do who have been working plantations? They have to find ways to survive because not everybody can migrate. While millions of folks were leaving the South, millions of folks also stayed behind. Part of my book kind of picks up on those who stayed behind to create a life for themselves.

SP: I love that about your book, that it ends with present day.

Smith: That was the hardest part, too, because so often when you do this kind of research, people always ask you, “How does the past connect to the present?”

What the book does in chapter three and four are directly connected because they’re located in the same area. What’s interesting about chapter three is that the same people who are sharecroppers and the people who organized the big cooperative in in Bolivar County in the 1960s, in chapter four, I talked about the rural Black youth. The Black youth farm is one mile down the same street from where the historical cooperative was.

Many of these Black youth are direct descendants of people who were doing this innovative work in the 60s. A lot of them knew nothing about this past because it was a past that wasn’t passed down to them.

L.C. Dorsey, the woman who led the cooperative in the past, she was interviewed in the 1990s. And she said, “If we had to do it all over again in the 60s, we would focus on youth more.” I see people today as picking up on what she would have done differently.

SP: Okay, I did have one last question. I write about restaurants in town, so I have to know what your favorite restaurants are in C-U?

Smith: So I’ve only been here six years, and I would say, it’s different for me because I am from the South, so I do love Southern food. It’s hard to get Southern food here, but I will say, of course, Neil St. Blues. I’m a regular there; I support them. I’m really big on supporting Black businesses. So Neil St. Blues, Caribbean Grill when it was open, and Wood N’ Hog’s barbecue‘s really good. The jerk rib tips at Wood N’ Hog are what I always get. Those are my spots.

Food Power Politics

by Dr. Bobby J. Smith II

Purchase the book from the publisher here.