I tried.

I really did.

I even went back and screened the film a second time.

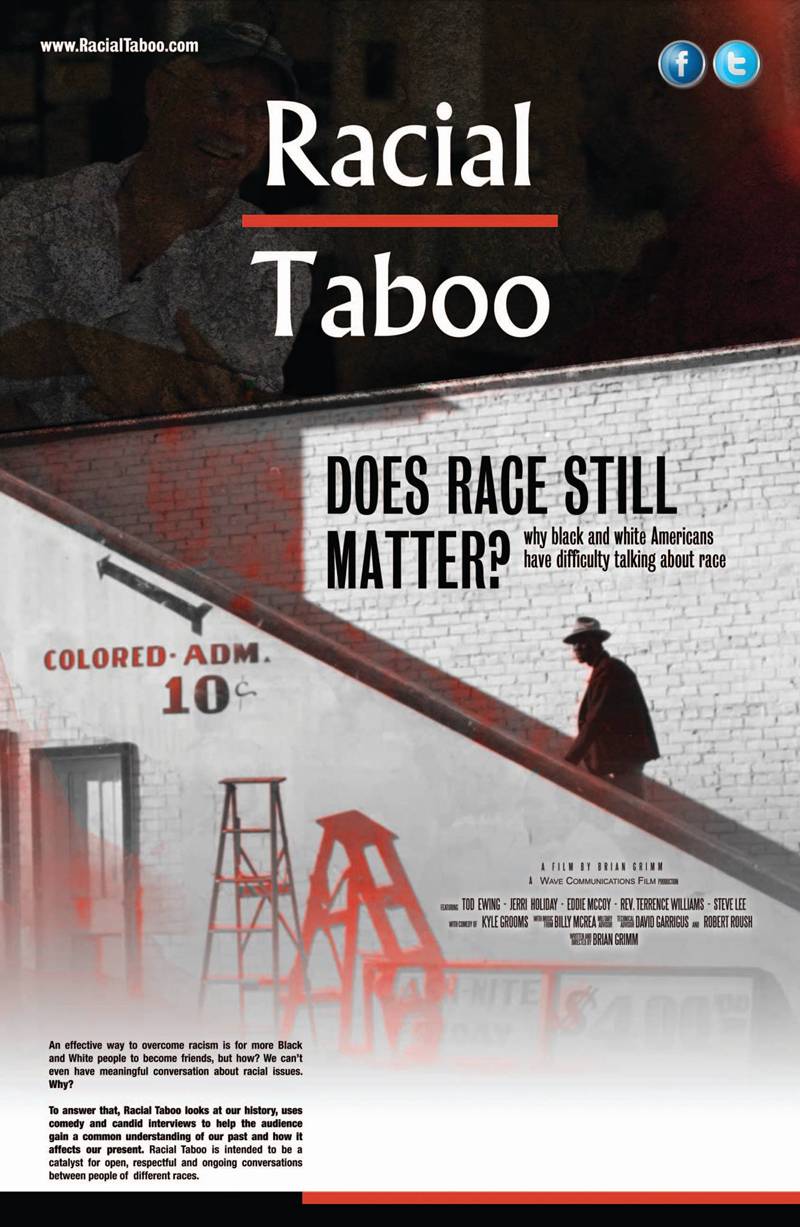

The first time I screened Racial Taboo in 2016 resulted in a letter to the editor.

However, it had been a few years since I’d seen the film. I’ve changed…the nation has changed…so perhaps my views on the project had evolved.

Also, because I do sincerely respect many of the individuals promoting Racial Taboo, I decided to view the film again.

In opening remarks before the March 4th Racial Taboo screening at The First Mennonite Church, the Champaign County Community Coalition facilitator Tracy Parsons lauded the fact that this film has screened 15 times across our community.

Parsons went on to remind us that “these kinds of gatherings are part of the commitment to loving our neighbor as ourselves” and he suggested “…these screenings provide one of the remedies to the fact that we don’t have enough safe spaces to talk about these issues. So this is just one of the tools available to discuss the most challenging issue in our society: the issue of race.”

I wondered: What makes this space safe, exactly? And what kind of safety is required for this conversation?

Sadly — despite the fact that the film has clearly been edited and several of the confounding aspects of African American life for director Brian Grimm have been removed from the discussion — my initial viewing assessment of Racial Taboo still rings true.

In that letter to the editor, I wrote:

Most disappointingly, Racial Taboo fails to explain how racial dialogue alone serves to address the troubling indicators of 21st century black America where blacks continue to lag behind whites in the areas of educational attainment, employment, home ownership, family wealth attainment, degree completion, incarceration and criminal justice and more.

However, this time, I came away asking even more questions.

Examining the funding model for Racial Taboo

Isn’t 15 times enough local support and funding for this project? I still don’t understand why my community is so deeply vested in screening and supporting this film financially (i.e., continuing to use county tax dollars and/or tax dollars and dollars from private donors to pay for Racial Taboo screenings).

According to Amy Felty, one of the lead organizers of the Racial Taboo Planning Committee:

The cost for each screening is determined by how many seats the venue holds, no matter how many or how few people attend. If the venue accommodates 200 people or more, the one-time cost is $750. For smaller venues, there is a sliding fee downwards…Many times, the film was paid for by others who sponsored it with planning and logistics help from our all-volunteer local Racial Taboo planning team of nine people.

Why, then, is there no room for discussion of other filmmakers — particularly films made by women and people of color — in an effort to support diverse viewpoints and spread the financial sponsorship of screenings to a broader, more diverse swath of filmmakers?

Disparate impacts: Why race, gender and generation inform one’s Racial Taboo Reception

In my small group, the white male facilitator himself mentioned that he felt that Racial Taboo is cautious and designed to make white people feel comfortable… but that is okay.

Consequently, a young black woman in my small group responded, “Well, if that is the case, why are we here? If this is a project designed for white people’s comfort, why do we need to be here? (Pointing at the two other African American women — myself included — and two African American teenagers she was sitting near).

One of the teenagers reported that “watching the teens in the film discuss school-based discrimination from teachers was difficult to even talk about” because the conversation was so close to home.

This exchange was clarifying and sobering for me: I realized quite starkly that we aren’t even  having the same conversation with one another at these Racial Taboo screenings.

having the same conversation with one another at these Racial Taboo screenings.

In my experience at Racial Taboo screenings, white people are grateful to be there and want to “have the conversation.”

Conversely, people of color attend these screenings and listen earnestly in the conversation and struggle with Grimm’s constructions of African American realities evidenced by audible groans in the audiences.

However, people of color and youth attendees want more than conversation. They also want actual change — political change, policy change, economic change, change in the way they are treated and dealt with when engaging with American institutions on the national, regional, and local level.

Assessing outcomes: Judging the “success” of Racial Taboo

Assessing outcomes: Judging the “success” of Racial Taboo

More importantly still: What exactly have Racial Taboo discussions actually delivered? What tangible gains, benefits, qualitative or quantitative change has our community experienced from these screenings that we keep financing?

If the screenings are “successful,” how do we know? Based on what indicators exactly? How are these indicators assessed based on age, race/ethnicity, gender, class, income, educational background, birthplace, occupation…

I have reached out to member of the Racial Taboo Planning Committee to pose these very questions to them, but to date I have not been able to secure a meeting with any of the planning committee members.

When I posed my concerns about the utility of continued Racial Taboo screenings at the March 2018 Champaign County Coalition meeting last week, several of the Racial Taboo Planning Committee often argued that “people keep coming” and that 1400+ people in our community have seen the film and that alone is “proof of the project’s value to the community.”

But how do we know that this response is specific to Racial Taboo when we have no point of comparison?

Do we know whether or not people would also support in the same numbers (or even greater numbers) other films that we as a county promote vigorously, pay for each time the film is screened and pay for the filmmakers’ transportation, room and board with resources gleaned from a wide variety of public and private benefactors — such as has been the case with Racial Taboo?

No. We don’t know the answer to this question because Racial Taboo has been the only game in town.

So, what kind of assessment tools exist to determine if Champaign County and its surrounding communities are any better off for these screenings than we pay for collectively?

Beyond Racial Taboo: Considering additional tools for examining Champaign County concerns

Champaign County is a community grappling with a range of disparities, as I discussed in an earlier column, MLK celebrations vs countywide disparities: Where Do We Go From Here.

We must consider whether or not there are other films and filmmakers that we might support that could help us consider our very particular dilemmas. Perhaps Whose Streets (Folayan, Davis, 2017) would provide a better tool for considering race, youth protest and policing? Perhaps They Call Us Monsters (Lear, 2017) would assist us in examining disparate youth detention rates in Champaign County? Perhaps The Force (Nicks, 2018), or Traffic Stop (Davis, 2017) could help us better examine our ongoing traffic stop challenges we continue to experience locally? Perhaps Prison In 12 Landscapes (Story, 2017), or Middle of Nowhere (Duvernay, 2012) might help us consider the impacts of incarceration on local individuals and families? Perhaps The Bad Kids (Pepe, Fulon, 2017) and Separate & Unequal (Robertson, 2014) will help us understand racial disparities and inequality in our schools? And perhaps Shell-Shocked (Ritchie, 2013), Armor of Light (Disney, Hughes, 2010), and Requiem For The Dead (Cookson, Desmond, 2014) can help us examine gun violence and armed threats against schools — both of which we are grappling with across Central Illinois?

Hence, I call for the Champaign Community Coalition to reconsider its singular commitment to Racial Taboo, and to consider other films and filmmakers whose works will aid us in “identifying critical community issues that impact the lives of youth and their families,” which is central to the mission of the Champaign County Community Coalition.

Nicole Anderson Cobb, PhD, is a four-time-UIUC alum and the newest staff writer for Smile Politely.

Photo by Nicole Anderson Cobb.

Assessing outcomes: Judging the “success” of Racial Taboo

Assessing outcomes: Judging the “success” of Racial Taboo