from Tao Te Ching, Verse 50

from Tao Te Ching, Verse 50

The Master gives himself up

to whatever the moment brings.

He knows that he is going to die…

He is ready for death,

as a man is ready for sleep

after a good day’s work.

(Stephen Mitchell translation)

People died this week. Farrah Fawcett, Sky Saxon of the Seeds, and Michael Jackson at age 50. (Or, age 12 if you read The Onion). More than one friend of a friend on Facebook complained about these reminders of death. One wrote, “OMG is it really that big of a deal everyone dies not trying to hate here just not big on death.”

The funerals are coming for all of us. The haunting Latin phrase instructs “memento mori” — remember you will die.

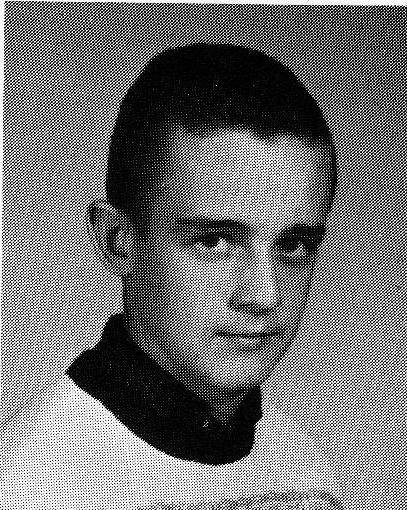

But enough people are celebrating the life of Michael Jackson right now, while I was given to remember the life and passing of my boyhood friend Bill Baxley.

Bill never wrote a hit song, or any song that I can remember. His obituary in the News-Gazette on September 7, 1992, lists the kind of accomplishments that don’t make national (or even local) headlines — a stint in the Army, a job as shoe salesman at Sears, and a position as manager of a liquor store in Urbana. He attended Holy Cross Catholic Church and sang in the choir. He graduated from Fisher High School the same year I had. He died at age 43.

The copy of his death certificate states coldly the cause of his death as cirrhosis due to alcoholism. But I know better. Billy died from the agony of living in the closet. I can’t ever remember seeing him drunk, but he drank — pretty much exclusively Budweiser — because he could not reconcile his nature with his religious convictions.

As his liver failed, I visited him in Covenant Hospital and all he could talk about was the upcoming high school reunion he had organized. He was so looking forward to seeing everyone. He died the next day. He was given a military burial near Mahomet, guns fired into the air for his service.

As his liver failed, I visited him in Covenant Hospital and all he could talk about was the upcoming high school reunion he had organized. He was so looking forward to seeing everyone. He died the next day. He was given a military burial near Mahomet, guns fired into the air for his service.

The reunion went on as planned, held in his honor, because above and beyond everything else, Billy was a friend. That was his role in life.

Bill lived down the street from me when I was in grade school. He had the distinction of being one of only two Catholic people I knew at the time in our small town of Fisher. We were best friends. We went to the Fisher Fair and won cigarettes at the arcade booths. We roamed the town at night and threw tomatoes at the Pumpkinvine train that rolled through town.

When we were 14, we tricked our parents into letting us see the Rolling Stones at Arie Crown Theater in Chicago. We had ordered the tickets without asking permission and, once we had the tickets in hand, they couldn’t refuse. We watched Jagger and Jones and Richards and Watts and Wyman perform, our first rock concert.

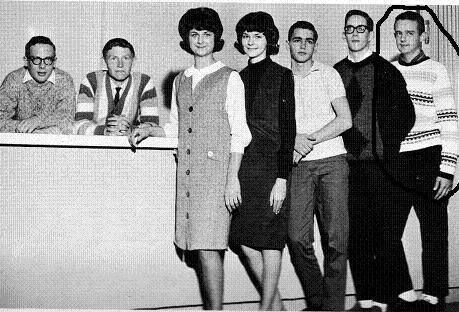

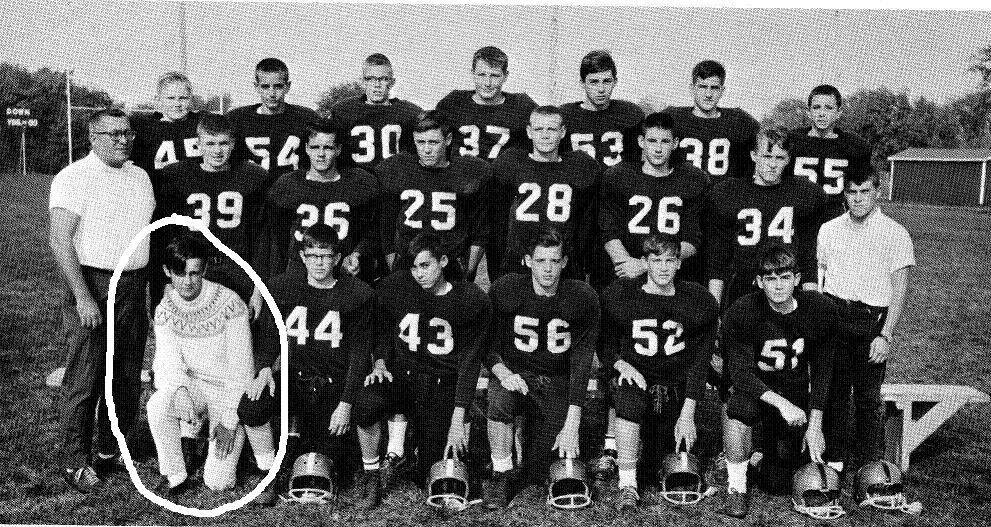

Bill didn’t play sports, but managed the football team and involved himself in almost every school activity. He introduced me to Natalie, a girl from Urbana he had met at art camp. I ended up taking her to the senior prom and, perhaps with Bill’s understanding and coordination, she helped me understand that my friend Billy was gay.

Bill was the first person I knew who was homosexual. I had a hard time believing it, at first. After high school, he went to Chicago to attend a two-year art school in the Loop. When I went up to visit him, he showed me the city, including life inside gay bars with Judy Garland imitators and a sense of community and freedom he had never known in the small-town fishbowl of Fisher.

And then we drifted apart. While I was out protesting the Vietnam War, Bill joined the Army, serving in Seoul, Korea, for a couple of years. There didn’t have to be a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in place in those days, because Billy lived “don’t ask, don’t tell” in every facet of his life. He agonized over his sexuality. He attended mass without fail and hoped he could be saved. Since the idea of having a same-sex life partner was not something society even considered in those days, he didn’t consider it a possibility either. He expected to live and die alone.

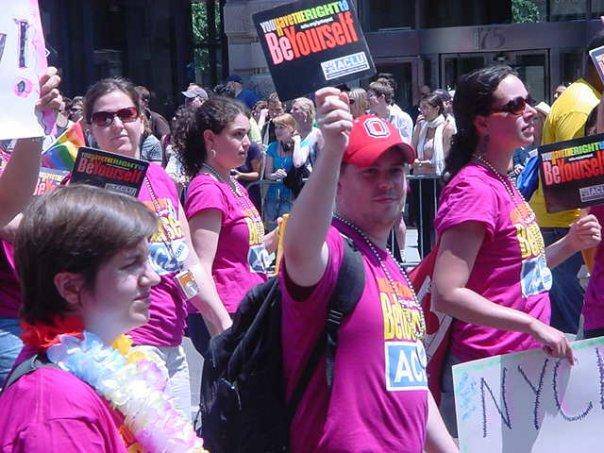

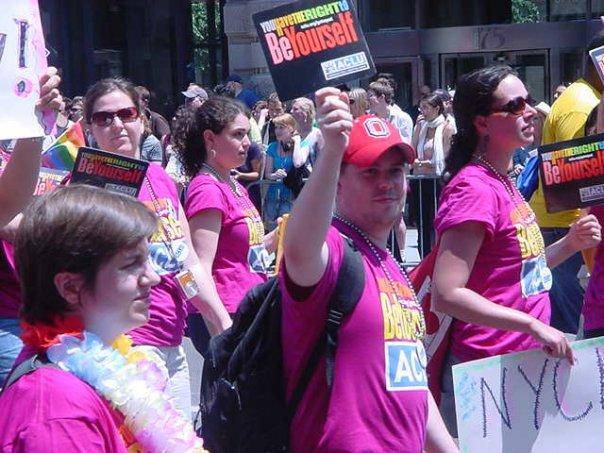

Apart from the death of Michael Jackson, there was something else this past weekend that reminded me of Billy. On Friday, there were two op-ed pieces in the New York Times about the commemoration of the Stonewall Riots in New York 40 years ago this week, the symbolic beginning of the gay liberation movement and the occasion for the annual Gay Pride week. The fact is that every year I need to be reminded about Gay Pride week. I tend to forget. Maybe gay pride parades have gone out of fashion, but if gay pride was ever needed by someone, it would have been Billy. Bill could fight as a soldier, but he could not conceive of fighting for equal rights for gay people. He could not have imagined a world in which gay marriage was a possibility. He couldn’t live with the truth of his life, always suspecting that it was his own flaw, always blaming himself for what he could not change.

Apart from the death of Michael Jackson, there was something else this past weekend that reminded me of Billy. On Friday, there were two op-ed pieces in the New York Times about the commemoration of the Stonewall Riots in New York 40 years ago this week, the symbolic beginning of the gay liberation movement and the occasion for the annual Gay Pride week. The fact is that every year I need to be reminded about Gay Pride week. I tend to forget. Maybe gay pride parades have gone out of fashion, but if gay pride was ever needed by someone, it would have been Billy. Bill could fight as a soldier, but he could not conceive of fighting for equal rights for gay people. He could not have imagined a world in which gay marriage was a possibility. He couldn’t live with the truth of his life, always suspecting that it was his own flaw, always blaming himself for what he could not change.

A few years ago, both of his parents passed away. Two of his brothers died before he did, which grieved his mother deeply, to have lost three of her sons. As far as I know, there are a brother and sister still living in the vicinity, but we have not kept in touch.

Maybe it is wrong for me to speak of Billy’s sexuality now, since it is something he strove so fiercely to conceal. But it is time, Billy, to bury the secret, to extinguish the lie, to pull down the shame that held you in its grip your whole life.

Our high school class in Fisher has not reunited since that year Billy died. In a very real sense, he held our class together. His life defined friendship and there is no greater legacy than that. .