My list of favorite books changes frequently depending on my mood and season of life. One that nearly always tops the list is a novel by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ called Stay with Me. Whenever I recommend it to others, which I do often, I tell them it’s beautiful, and devastating, and reading it is a lot like getting punched in the gut over and over again. As I was reading Caleb Curtiss’ new poetry collection Age of Forgiveness, I found myself reminded often of Stay with Me. Not because of the content or writing style, but the simultaneous beauty and devastation in Curtiss’ words very much reminded me of Adébáyọ̀’s novel about a very different kind of loss. As I was reading it, I knew that like Adébáyọ̀’’s work, I would be thinking about these poems for a long time. And yes, there were many moments reading the collection where I felt a lot like I had been punched in the gut.

Although Curtiss now lives in Delaware, he is a Champaign-Urbana native. He attended Central High School and is an alumnus of Parkland College and the University of Illinois. He also co-founded and directed the PYGMALION Literary Festival (and is a former arts editor for Smile Politely). Curtiss is the author of the chapbook A Taxonomy of the Space Between Us, and Age of Forgiveness is his first full-length collection.

Age of Forgiveness opens with two epigraphs. The second of which, written by psychiatrist and trauma-expert Judith Herman, reads, “The survivor imagines that she can transcend her rage and erase the impact of the trauma through a willed, defiant act of love. But it is not possible to exorcise the trauma, through either hatred or love.” Although the title speaks of forgiveness, this epigraph in particular better manages the reader’s expectations. Many themes run throughout the collection: the capturing of a memory, of a moment; nostalgia; death and violence; religion.

The collection can be read as Curtiss grappling with his sister’s untimely death and their shared childhood trauma. Moments of violence are interwoven with more peaceful vignettes, and there is a sense of an attempt to capture how things both openly meaningful and less obviously so end up intertwined in a life story. Rather than starting with a death, the first poem deals rather with a birth of sorts: “Possum” depicts baby kits emerging from their mother’s pouch “to climb onto your back / and into the world, / thinking fondly of you, …” It’s a quiet opening to the collection, easing the reader into thinking about familial relations, and the dangers that can await you once you leave the safety of your mother’s care — or perhaps, even before.

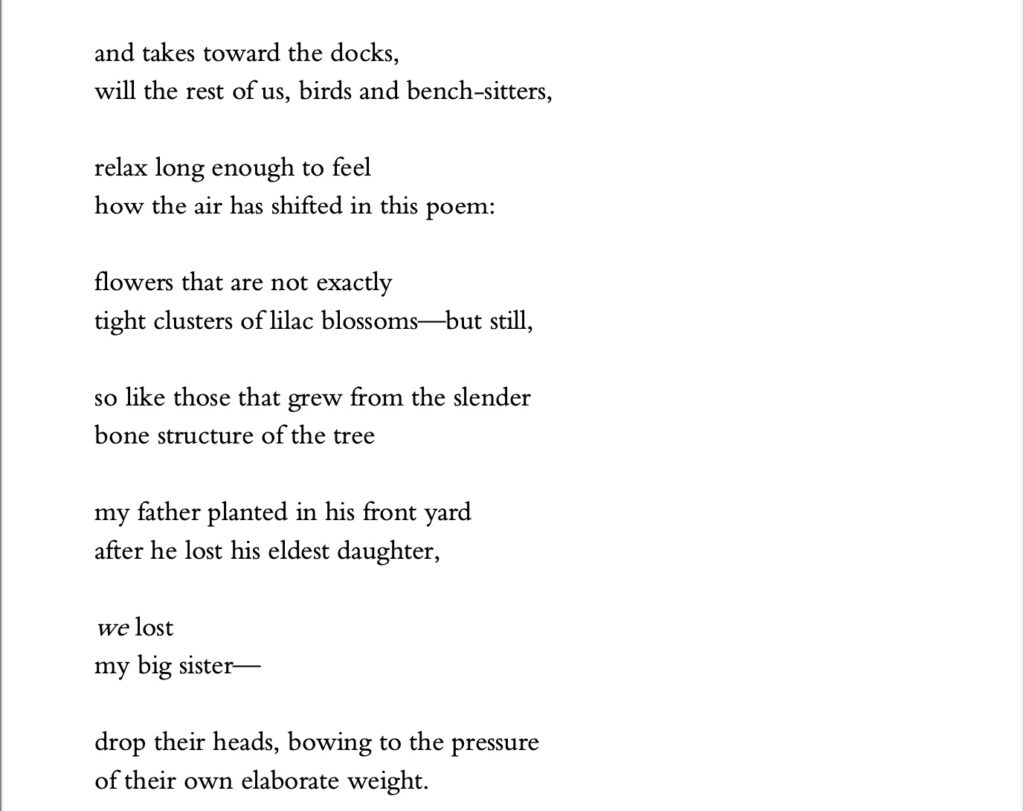

From “Possum” we move to “Photo Shot on Undeveloped Film,” a portrait of a young boy and his older sister on a summer day. The two opening poems are more simplistic in style, primarily made up of 2–3 line stanzas, with each line often made up of only a few words. This stylistic simplicity starts to shift in the third poem, “A Kind of Purple,” which first reveals the older sister’s death. The lines that reveal this loss are notably the shortest of the poem reading only: “we lost / my big sister—” Their length in comparison to the rest on the page stands out visually so that even if you flipped through the collection, your eyes would naturally be drawn to that revelation sitting at the bottom of the page — a careful and deliberate stylistic decision that delivers a big impact.

Curtiss’ mastery extends beyond the writing of the individual poems. The collection as a whole works really well together, in a way that is not always accomplished in longer poetry collections (and is particularly remarkable for a debut full-length collection). It’s possible, of course, to read the poems individually — and many of them were previously published on their own in various outlets. But all together, they create a carefully curated story. “God Forgives,” for instance, is one of many that invokes religious themes. Here, we see arguably a mockery of God’s apparent forgiveness for all sins, no matter how perverse, but the poem ends with questioning what happens to the victims of those who are granted God’s forgiveness. In this case, the victim is clearly the now-deceased older sister, whom the reader already feels quite connected to from the other poems.

It is not an exaggeration to say I could spend time discussing every single poem in this collection. Curtiss is a talented poet, and he weaves this story, no matter how tragic, really beautifully and in interesting ways. He takes risks with form and style, particularly in the later poems. Section four, for example, is made up of only one poem: “I am Whole, I am Whole.” Written in prose, the three-and-a-half-page work traces the speaker’s attempts to water plants on a regular basis. The poem provides some moments of levity in this relatable endeavor:

And then suddenly, another me: someone to water the plants! Someone who knows which plants require greater or lesser amounts of water; which plants benefit from a more syncopated watering schedule as opposed to an especially predictable one; which plants have succulent leaves in need of spritzing and which have waxy leaves in need of having mayonnaise rubbed into them monthly. (That, if you did not know, is something that people do with their plants.)

[…]

Someone who will engage in the good work of supporting my yucca, a plant I did not even know I had. Hey, where did you come from, little Yucca? No answer. OK. […]

One of my other favorite lines comes from the opening poem of the final section, appropriately titled “Poem,” and opens, “This poem has no occasion, I edited that part out. / Like a body, or a memory, it has rebuilt itself over time.”

This collection could easily be read in one sitting. Although it’s just over 100 pages, it goes quickly. Yet, I don’t think it is intended to be read in that manner, and I would advise against reading it in a short time frame. While I’ve focused on more of the not-so-quietly somber moments throughout, the collection also offers ways forward. A work like this deserves for you to spend time with it, soak up the words and the feelings, and everything in between a little at a time.

You can purchase Age of Forgiveness on bookshop.org, or, naturally, from that other website that sells books.