Kambui Olujimi’s The Rock that Cuts the Night in Two at the University Galleries of Illinois State University surveys decades of work in one exhibition. Olujimi is a Brooklyn-based, Columbia-educated artist. He is, in many ways, the definition of a multidisciplinary artist: he paints, he sculpts, he makes videos, installations, and prints. Looking at this survey of nearly 20 years of work, it’s clear that he uses the material necessary for the project.

In late September, Olujimi was on campus for a lecture and opening reception. His talk was casual, and he told the audience the story of the evolution of his practice, discussing what I’d call the organizing principle of his research, which is creating sites. Curator Kendra Paitz created moments for viewers to sit with the work and uncover their own relationship to the material and subject matter. It’s a well curated exhibition that offers viewers a true sampling of Olujimi’s artistic production, and the common themes therein.

The largest pieces in the exhibition are the tapestries from his Wayward North series (2010; install pictured at top). The subject matter is drawn from Olujimi’s novella of the same name, which explores mythology through his own personal narratives and experiences, as well as global events. You don’t need to have read Wayward North the novella in order to appreciate and understand the general ideas illustrated on the tapestries. Each tapestry represents one month of the year, and presents different constellations and vignettes from the novella. They are huge, and there simply isn’t wall space for all of them to be on view at the same time. Instead, the gallery has been swapping them out each month the exhibition is on view, that way patrons are able to see three different ones, which makes for an entire season’s constellations. These star maps are on huge pieces of quilted fabric, with white embroidery and rhinestones. The imagery is illustrative and elegant, particularly when human faces and hair are depicted. I love work like this because it requires from the viewer a particular type of performance in order to fully appreciate it: you have to step back far enough to see the entire thing, but when you step in closer, you’re able to see the intricacy of the embroidery and the details of the rhinestones, which offer a shimmer of light when viewed from afar.

Speaking of shimmer: one of my favorite pieces was a 2017 sculptural installation titled Fathom. Made of six chandeliers, rubber inner tubes, and wooden pallets, it was shimmery because of the light and glass, but grounded with the heavier, earthen materials of wood and rubber. It was a quasi-life boat on the floor, made of found objects of varying delicacy, that required both care and attention from the viewer to see all of its components. It’s easy to imagine this contraption floating on a sea, a beacon of light in darkness, an object against which to understand or know or ground oneself. Fathom was located in a smaller space adjacent to the Wayward North tapestries, creating a lovely visual poem about navigation, finding one’s way, mapping and place-finding, with the works acting as guideposts.

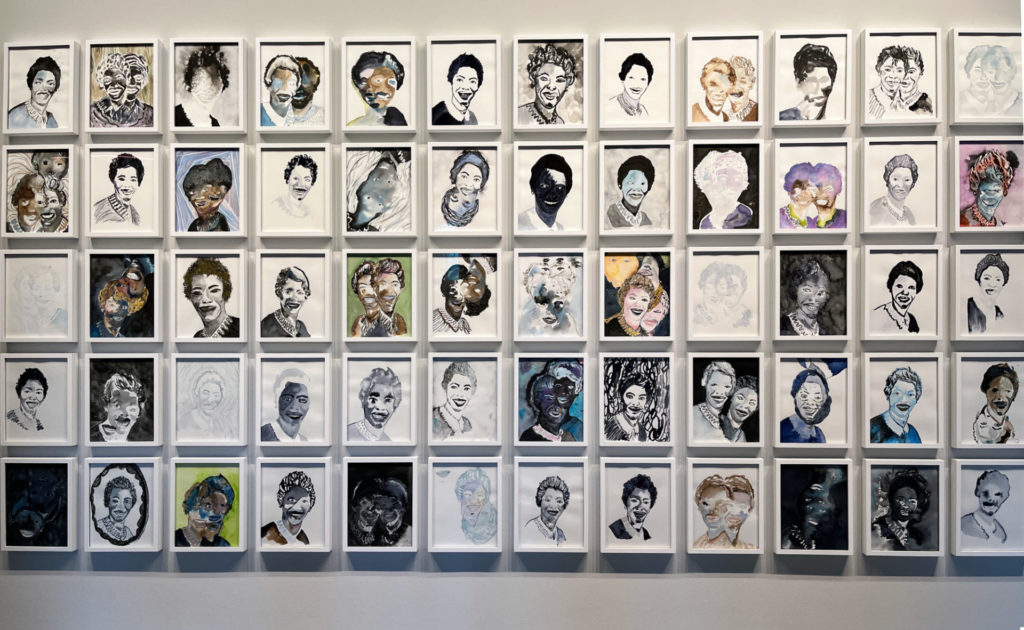

Walk With Me is a series of portraits of Catherine Arline, a beloved community member and leader in the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, as well as the city of New York, and Olujimi’s “guardian angel.” Arline died in 2014; these works on paper are a meditation on grief and memory, completed in the five years following her death. Sixty of these portraits are installed on the entry wall to the galleries, and make for a striking introduction to the exhibition. Here, Olujimi and Paitz have created another “site” that requires the push and pull of viewership. In order to see the entire grid, you must stand back. In order to see the detail, nuance, and differences between each work, you must get close. Each of the sixty pieces are ink on paper, using the same reference image of Arline as an 18-year-old, newly arrived to New York City. Some are more detailed, offering a slower read of the image. Some are faster, inkier, harder to differentiate details and facial features. Like memory and grief, individually they offer a different experience of that moment, and create a fluidity between what is beautiful and what is ugly, what is tender and what is violent, what comforts and what hurts.

The largest space in the University Galleries featured prints, photos, and video work from the artist. There were a series of long-exposure photos from his Blind Sum series, which is about Depression-era dance marathons. Dance marathons were just that: dancing that lasted weeks or even months. Inspired by these events, Olujimi has made work in a variety of media that explore what he notes as the “endurance, defiance, and a desire to live beyond the capacities we have internalized.” Historic dance marathons were almost exclusively white, but white people were exclusively not required to endure, defy, or desire in the same ways as Black people. Olujimi considers these ideas from a Black person’s (or dance couple’s) subjectivity: What does it look like or mean for Black people to perform in these ways, given the realities that faced them (and that Black people continue to face)?

Staying Afloat (2016) is a video that shows the artist ascending a constructed platform and jumping rope. It’s a relatively short piece, only two minutes and 27 seconds. For the first minute, minute and a half, Olujimi, dressed in white leggings, white and gray gym shorts, and a white hoodie, attempts to jump rope. He’s successful for a few seconds, jumping on one foot, then the other. His misses. The rope catches. He tries again. But then something happens, a glitch, almost: the video shifts to show him floating, hovering above the narrow platform, the rope traversing the vertical space around his body with ease. (It’s edited, of course.) This is perhaps one of the more direct works: you can “get it” by watching the video and reading the title. It’s about staying afloat in a world that will do anything to drown you, especially as a marginalized and historically excluded person. According to the artist, the video is also a reference to the Muhammad Ali quote, “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” Olujimi notes on his website that this piece “commemorates the political and humanitarian services of the late champion” who died in 2016, the same year this work was made. In a world where there is so much precarity, the ability to edit yourself to stay afloat is incredibly enticing, fantastical even. As a viewer it’s easy to take for granted the effort of the edit, the hours and of tedious work to cut and bring together the video. Olujimi leaves in the sound of sneakers on wood, of the jump rope smacking the platform. The edit isn’t easy at all; he had to do all that physical labor in order to have a video to edit in the first place. It’s an allegory for all the work that people endure in order to stay afloat in their lives, to avoid foreclosure and hunger, pervasive sorrow and despair: To avoid falling off the platform in a tangle of rope.

As I noted, all of the works in the show can be read through the lens of site-making, both within the context of the subject matter but also in the installation and relationship the viewer has with the work on display. I enjoyed thinking about individual works as their own sites, but I also enjoyed the moments of dialogue between works and rooms. I left the exhibition thinking about the content of Olujimi’s work: the exclusivity and absurdist whites-only dance marathons; the creation of one’s own mythology through storytelling and image-making; what it means to swim in the seas of grief, sorrow, and memory. I also left the exhibition thinking about site-making as it relates to those ideas: who is included, who is not; which geographies are prioritized; what does it mean to build and participate in community?

If you’re looking for something to draw you out of Champaign-Urbana for a few hours, I recommend a trip to ISU’s University Galleries. The galleries are beautiful, and The Rock that Cuts the Night in Two is a wonderful exhibition that extends an invitation into Olujimi’s world, a site worth visiting.

Kambui Olujimi: The Rock that Cuts the Night in Two

University Galleries of Illinois State University

11 Uptown Circle

Normal

M-Th 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

F 9:30 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Sa + Su noon to 4 p.m.

(Closed Nov 15-19)

Through Dec 10th

Free