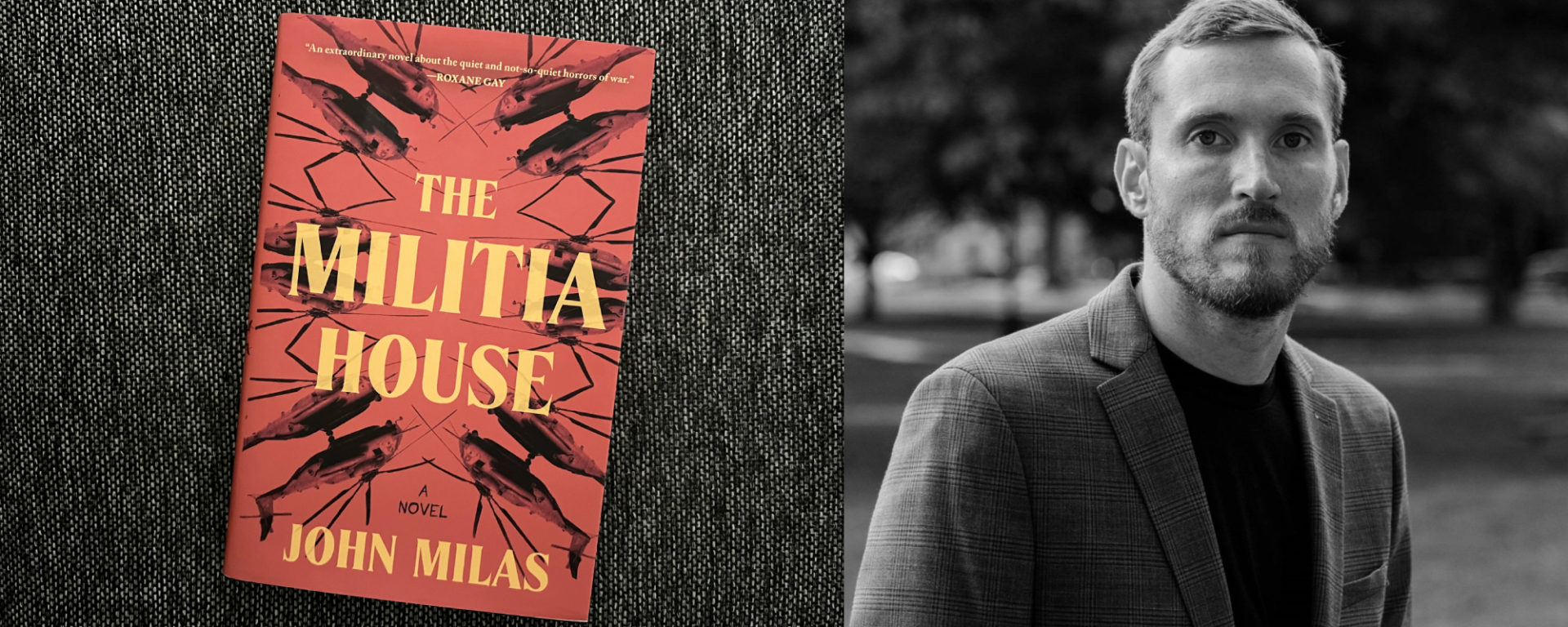

In many ways, John Milas is a product of Champaign-Urbana. He grew up in Champaign, attended public school, completed a year at Parkland before enlisting in the Marine Corps, and returned to complete his undergraduate degree at the University of Illinois. He is even a former Smile Politely contributor. Milas’ debut novel, The Militia House, was released earlier this summer.

The Militia House is a work of Gothic horror — more specifically, military horror. Milas, who served in Afghanistan, introduces us to our main character, Corporal Loyette, and his subordinates, junior marines Lance Corporals Johnson, Vargas, and Blount. They are serving on a military base in Kajaki, Afghanistan in 2010, right during the height of the war. They’re trapped in a tedious, seemingly endless cycle of loading and unloading cargo planes and helicopters. Just off base is a Soviet-era barracks with a troubling history, an abandoned building that intrigues these four men. They sneak off base and enter this site of rumored atrocities. When they leave, the four men are changed.

The Militia House is a haunted house story. As his MFA advisor Roxane Gay noted, it’s a “novel about the quiet and not-so-quiet horrors of war.” As someone who has read a fair number of novels about war, this one is different. It sits more soundly in the realm of terror — that which evokes fear, both psychologically and emotionally — than in that of blood-and-guts style horror that is meant to disgust. The novel is sad and unnerving, disturbing and tense. There are vignettes I keep returning to, many weeks after reading it. It’s a powerful book worth reading, even if you are not typically a reader of horror.

The novel has been praised by The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and many others. Gay selected it for her Audacious Book Club (check out book club chatter here). You can read additional interviews with Milas on his website, and listen to a playlist he curated for the book here.

I recently sat down with Milas to talk about the book, his process, and what it’s been like returning to Champaign-Urbana.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: How did you become a writer?

John Milas: That’s a good question. I don’t know. I think that I was just inundated with stories as a child. I was raised in a religious household, so the constant exposure to the Bible was a big thing, because there are so many narratives. I was often read to by my parents or told bedtime stories, that kind of thing. I always liked telling stories. I never really learned about how to tell stories, I just knew it was fun to do.

After I was done with my time in the Marines, I came back to school [at the University of Illinois] and majored in creative writing.

I don’t know if people really become writers; I just enjoy storytelling and reading, but with the GI Bill there was an opportunity to be intentional about it. Then I went to grad school from there. So these opportunities opened up to keep pursuing it. I don’t do it as my day job, but obviously the book is something that has come to fruition after a long period of time.

SP: You started college, then enlisted, and when you left the military you went back to school. How do you think that interruption affected the way you approached your education, coming out of the military?

Milas: I completed one year at Parkland and then went to boot camp the following August. After [the Marines], being a non-traditional student, gave me… I had certain life experiences that were behind me and it was easier to focus on taking my courses seriously. I definitely had classmates who also did, but there were a lot of people who were coming of age and having all the weight of growing up and being away from home. As a townie, there wasn’t much of a transition to coming back here. So it just made it easier to take it seriously.

I think being older helps you stand out for your instructors. I certainly was infantilized as an undergrad, but I was also taken seriously and treated more like an adult than a lot of my classmates. That helped me take myself more seriously.

[School] didn’t scare me. After being in the Marines for four years I really was not afraid to be told no. I had been told no in many different ways, whether or not I was even asking for anything at the time. The faculty were really generous and approachable. There are a lot of cool opportunities for undergrads here. There are a lot of interesting creative writing classes that are not really offered widely at Big Ten universities. I got to take a craft class and one of the things that was emphasized by the instructor was you can and should be influenced in inverse ways. That pushes you toward your own tastes or your own process. It’s important to change up your practice to figure out what doesn’t work when you’re young. There’s no use [in] being afraid to try something if you haven’t done it. It might work, or you might hate it and you’ll know never to do that again.

SP: You’ve talked in other interviews about the difference between horror and terror. We often conflate the two in the way we talk about them contemporarily. More importantly, these genres allow us to tap into something else that is happening culturally or socially. How do you use the tropes of genre to talk about contemporary issues while keeping things fresh and new? Which issues in The Militia House do you hope resonate with readers?

Milas: If you have a character who is not very introspective, you have to find other opportunities, get all your mileage from flies or porcupine quills. That’s more gimmicky, I think.

I really hope that The MIlitia House can be on a bookshelf with spooky stories and other horror books. It can be read that way for fun, but what’s novel about it is exploring the lifestyle that one particular subject position was exposed to overseas. So many narratives [about war] are focused on the immediacy of death, people getting blown up. That’s not a new type of story about war. Superficially, I thought there was an opportunity to talk about the job I did, which was in logistics. [I wanted to explore] the non-infantry side of the Marines, and that routine and the monotony, and how it can be scary. And, obviously, the overarching failures of the whole effort to win the war. That’s definitely important to me. It would be a really disingenuous book if it didn’t have a focus on that. My book’s not really pro-Marine Corps.

Bringing in genre will bring in fans of the genre who maybe wouldn’t have heard that message before. People can be brought to the table who wouldn’t have been there if it wasn’t a horror story. Who knows, maybe people will read the book and not even notice it’s a staunchly anti-war book. That would be a compliment. Then it wasn’t taken as a really didactic treatise.

SP: The men in the book really struggle to connect with each other. The main character, Loyette, is saying that he cares about and wants to connect with his subordinates, the junior marines, but he does not express those things clearly. Instead of saying “Hey, how are you, I want to ask you about your life,” he says, “How old are you?” Can you talk about your experiences writing these male characters who are so disconnected from each other?

Milas: I think the way to break that down simply is to describe the Marine Corps. If you’re on active duty, it’s a full lifestyle. It’s way beyond just a job. Your rank is describing where you are in life, not what your job is. ‘Cause your job title isn’t your rank.

You can never be earnest or proud of anything, ‘cause then your friends will roast you. If you ever wear a USMC t-shirt on base, your friends will be like, “Hey bro, are you in the Marines? What?!” It will be that kind of thing. You walk a fine line: if you vocalize that you care too much, especially too often, then that becomes meaningless. Everyone learns the same things about leadership. Tough love? I think in the civilian world it is a toxic thing. In the Marine Corps, that is the life. That is the life you asked for. No one gets drafted anymore. When you wake up in the morning, you know you have to answer to someone. You know someone’s gonna be a dick, someone’s gonna tell you what to do.

In the context of these characters, I think it’s good for a reader who is outside the lifestyle to maybe be shocked by that, by the distance.

SP: So much of the book is about what is or isn’t known or what is or isn’t true. I was wondering how you thought about that when you were working on the book.

Milas: What does the character know, what do they even think they need to know? A lot of military books are written by people who were officers, who were designated leaders who were constantly in meetings and briefings and were informed all the time. If people see only that, then that’s what they think it’s like to wear a uniform. It was important for me to portray the enlisted side.

For what it’s worth, that insularity of the four characters we follow is absolutely a criticism of the structure of war and the military industrial complex. Hopefully an ambitious reader will also see that these characters are withheld the big picture. I read a review of my book that partly criticized me for not including any Afghan characters — [while enlisted] I didn’t engage with any! I think it’s fair to criticize that, but it shouldn’t be a criticism of the book, it should be a criticism of the function of the deployment, in my opinion. We were completely in a bubble, just moving passengers and cargo. I think that’s problematic. Some people I know aren’t bothered by that, by the big picture. For me, the Kafkaesque institutional absurdity of it is going to weigh on me for the rest of my life.

SP: A surreal disconnect.

Milas: Yes. A lot of cognitive dissonance.

SP: I imagine that being asked to repeatedly talk about a specific and/or difficult time in your life, even though you’ve written a book about these things, is surreal. What has it been like to do all these interviews where people keep asking you to rehash that moment?

Milas: It is interesting and weird. Because the time I spent [in Afghanistan] is something I’ve thought about a lot; maybe I’m just more ready to talk about it. In this case, every once in a while I’ll call my friends, and ask “did this really happen?” and they’ll retell the story. We kind of help each other — or maybe it’s not helpful to keep these memories in each other’s heads — it’s definitely surreal to have been out of grad school and have this been my thesis, and now suddenly I’m talking to everyone about it.

SP: How do you define those boundaries between your life experiences and the stories you tell?

Milas: I like to blur them as much as possible. That’s what interests me about fiction, actually. I don’t know if there’s an obligation in fiction to tell the truth, whatever that is, or be authentic. I prefer to do that, so I like to pull from things I’ve seen or experienced, or places I’ve been. I just feel more charged up about it. I like to write about true emotions, maybe that’s what it is. True emotions that I’ve felt in certain settings then blur the line. Smudge the brushstrokes. A lot of the stories I have published are based on actual scenes that I’ve experienced, or stories that other people have told me. There’s a kind of spin on it so that people can’t be like, “That’s about you,” or “That’s about me.”

SP: When I was reading the book I kept returning to the idea of boredom as a theme or genre. What role does boredom play in your creative practice?

Milas: I daydream a lot, basically nonstop. It’s probably insufferable for people to be in person with me at times. Boredom, I don’t know. In some ways I am an easily bored person, and in some ways I’m not.

SP: In the book it was this albatross, and also this great motivator.

Milas: I think it also can run alongside the terror because the characters might be bored, but the reader knows something’s cooking in the oven. Something’s gonna happen. The characters don’t quite know yet, or the narrator doesn’t think they know.

SP: What is the last book that made you cry or laugh out loud?

Milas: That’s a good question. I’m reading a bunch of books; what was the last one I finished?

SP: Maybe that’s the question: What’s the last book you finished?

Milas: Gus Moreno — he wrote this novel This Thing Between Us — it’s also a gothic horror novel. Without spoiling too much: We’re orbiting a death, there’s a funeral and people are mourning, but the humanity of the characterization is also very funny. The opening of that book will make you laugh and cry at the same time. And it’s very scary! It’s kind of a miraculous book.

SP: What’s the biggest change to Champaign-Urbana from your childhood to now?

Milas: My least favorite change is [the closing of] the Art Theatre. I was so mad! That was easily my favorite cultural fixture.

SP: It’s a great loss.

Milas: Yes. It was such a cool, laid back thing to do. And I didn’t just see late night horror movies, I saw current release art house movies.

SP: What are your favorite Champaign-Urbana things?

Milas: I do trivia at Rose Bowl, good vibes there. On Sundays I meet up with a friend and we’ll usually get some writing done at Cafe & Co and then go eat at Bunny’s. I really like Esquire and Bunny’s a lot. I like places where the owners and the employees have a sense of pride and are treated like humans and don’t wear weird uniforms and stuff.

El Toro gave me a flaming shot for my birthday last year, so I’m a big El Toro guy now. I get Fernando’s food truck on campus way too often, that’s for sure.

You can order The Militia House from Jane Addams Books or The Literary. Follow Milas to learn of upcoming author events on his Instagram page.