The Hawaiians have a saying: from mauka to makai. Uka is mountain and kai is ocean, and the proverb reminds us that everything is connected. There are no mountains in Illinois, but for Lanialoha Lee, raised in Chicago and in the “old ways” of Hawai‘i, the city is our uka and Lake Michigan our kai. The Pacific may seem far from us here in Champaign, but our waterways are connected. Surrounded by the Mississippi and the Great Lakes, we too live in a sea of islands.

That is what Lanialoha Lee and her two children came to Spurlock Museum to share on Indigenous Peoples Day. They began with a chant to introduce themselves and their stories to Urbana and to ask permission to be on the lands of the removed tribes of Central Illinois. They hope to form a bridge that connects Champaign-Urbana to Chicago and the Pacific.

In May of this year, Lee opened Chicago’s Legacy Hula at the Field Museum in Chicago with a chant to greet the sunrise. The opening marked two auspicious events: the 130th anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893, and the arrival of hula in Chicago. For over a year, Lee had been recategorizing the Field collections — kāhili, or feather royal standards that could only be gifted by ali‘i (royalty), had been labeled as fly swatters — and digging up records of ali‘i and kumu (teachers) across the city. The chant and the exhibit together bring the Pacific to Illinois, where it has become an integral part of the cultural landscape.

Hula in Illinois is personal for Lee. Hula first came to Chicago for the World’s Fair on the eve of the overthrow, making the city a key site for continuation of Hawaiian culture in light of the American occupation of the islands. That same hālau (school), established by King Kalakaua to lift the kapu (taboo) restricting hula to the ali‘i, became the kupuna (ancestors) of Chicago’s hula legacy. And they were not alone. Lee realized when she saw the kāhili lining a wall of the Field’s vast storage rooms that Chicago has its own ali‘i. Princess Victoria Ka`iulani Kawēkiu I Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn was there to smuggle newspapers to Queen Lili’uokalani when the queen was under house arrest after the overthrow, and she would later come to Chicago, where her children became stewards of Hawaiian culture in the Midwest and her hula legacy would lead to Lee and the Aloha Center Chicago.

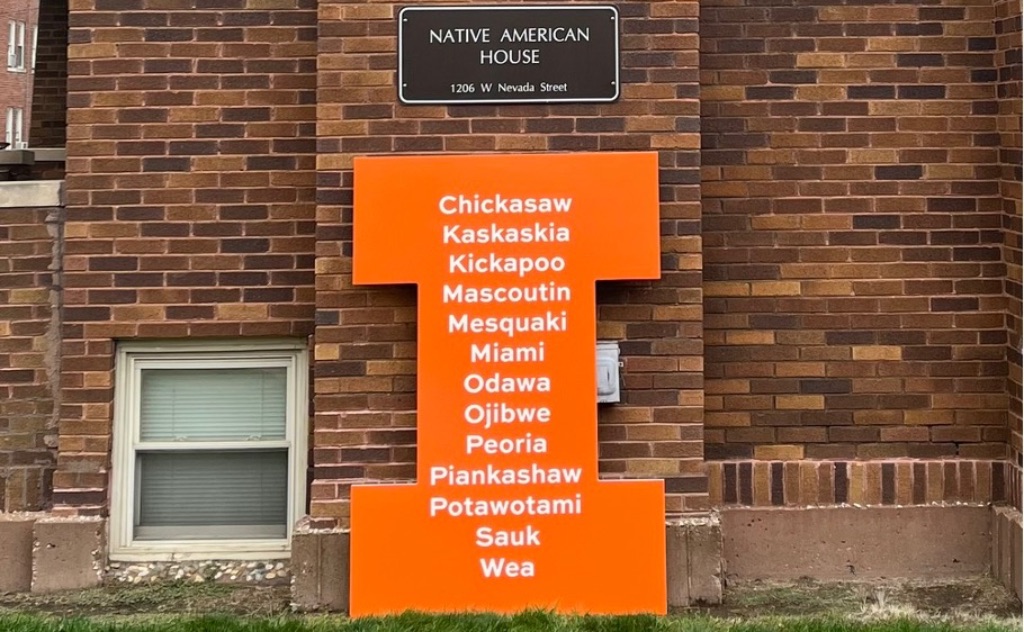

As a kumu hula, Lee is very clear who she descends from. You can’t just be a kumu hula by knowing hula, she says. You must ask, “Who is your kumu? Who is your kumu’s kumu? And, who is your kumu’s kumu’s kumu?” Two of Chicago’s four master teachers taught Lee. She began studing with Caroline Namahoe Ha‘o, who then sent her to learn under Bill Ka‘ulu Charman, who pioneered a Chicago style of hulu and performed it through the country as part of the U.S. Air Force. She is now passing hula down to her children, Kahookele Napuahinano Sumberg and Kū Kamaehao Sumberg, and she continues to teach and practice hula as part of the work of the Aloha Center. For Indigenous Peoples Day, hosted by the Native American House and the Spurlock Museum on October 9th, Lee was joined by her children to extend the legacy just a little bit further. Their chant is an act of protocol. As Lee explained, “The chant asks permission,” recognizing a kuleana (responsibility) to create interconnections between Hawai‘i and the Indigenous peoples whose land is occupied by the university. Lee has been teaching and performing hula since she was a child, and Kahookele and Kū are the fourth generation to practice it in Illinois. Spurlock is now part of that legacy, implicated in the responsibility we all hold to each other, a responsibility Lee went on to explain as part of her talk.

As her children sat quietly, their necks craning around to see the faces of Chicago hula performers and kumu past and present, Lee outlined a history that began at the Columbian Exposition and continues at the Aloha Center. “I never knew life without fighting for our Native Hawaiian Rights,” Lee recalls, pointing to a picture of Ha‘o and proudly identifying her as her grandma. “We might be one of the three Indigenous recognized by the United States, but we are still the one that is yet to receive federal recognition.” Without this kind of government-to-government recognition, Hawaiian land continues to be illegally occupied. Hula itself has been treated as a form of entertainment, where Lee shows it to be closely tied with protocol and cultural practice. Clothed all in black except the hand-dyed wraps tied around one shoulder, her children offered a hula for Indigenous Peoples Day that remembered a century old relationship between the Pacific and Illinois.

After her talk, Lee sat down with me to speak about what it means to be Hawaiian in Illinois.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: What brings you to Champaign-Urbana?

Lanialoha Lee: I’m here for the second round of trying to grow bridges between Chicago and C-U through the work at the University of Illinois. We’re trying to increase the presence of Native Hawaiians side-by-side with Native Americans on events that are appropriate. We certainly don’t want to be overpowering. It’s not our space; it’s their sacred space. For the past 30 years, we have really had a lot of fun growing together. We go when our neighbors are going maple tree tapping, and they do what we do. They do their prayers just like we do for ours. The cultural exchange to be had was so impacting for me and the kids that I have continued as they have gotten older, and now we’ve got 30 years of work behind us together. I feel like now we have the capacity to sit down and chip away at these things that both our communities are addressing to help one another make a difference. I didn’t really know it was going to grow, but Illinois was a great place and great way to grow it.

SP: I am really intrigued by the connections you were making in your talk between Hawai‘i and your role here in the Midwest. You mentioned that Hawaiians are not able to make canoes because the remaining Koa trees are not fully grown. [They were cut down to make souvenirs for tourists.] Can you say a little bit more about how you see that connection between what’s going on in Hawai‘i and what’s going on here?

Lee: That was a scary moment as the Polynesian Voyaging Society stood in the Koa forest and discovered that there were no longer any Koa trees. They still had the task of having to build a traditional Hawaiian double hull canoe, the style wa’a they used to travel the globe. So they had to borrow. They went to Alaska, asked for help, and they decided that they could use those trees. But, before they could accept the gift of two trees, they still had go to Alaska and do it the way we did it at home. You have to ask permission: They feasted at the base of the tree. They all went wala au about the wa’a; they had to visualize the route down the mountain.

So, when I think about that, we don’t have trees at all, but they’re traveling. We’re waiting for them to come with the kālai wa’a, come sail to Chicago. As I start to envision what the Aloha Center Chicago needs to become, we have no wahi pana [meeting place], we have no kino lau [native plants], we have no place to gather. So, there’s one of our twin towers. One has to be for commerce, the home, the roof, where all of the Native Hawaiian organizations are able to grow and make income, while remaining who we are as a people. The other one has to be the place where we grow all of our Indigenous plants. I’m sure we can bring haupana tree, we can bring ulu trees, we can bring all the trees where we can create and harvest and have our own Hawaiian foods. Hawaiians were one hundred percent healthy. We were paddling, we were swimming, we were surfing, we were hula, we were agriculture. We built everything we had to build. That idea of growing over here is really growing the sacred space we need for all Hawaiians and others to be able to come and gather.

SP: I know your production company is Pacific Soundz (vs. Hawaiian), so how do you see yourself as part of the Pacific, as well as Hawaii?

Lee: I think my responsibility has grown into my having to be able to produce music. I get requests, and that’s usually coming from the people who hail from those islands, and I never lie. If I got it, I’ll do it. Like, if I do a Samoan song, they come up with a kind of purpose, and they’ll ask, “How did you learn that song? Who taught you?” And I’ll tell them, and then they’ll nod and say, “That’s an old song. No one knows that here so that only means that you had a teacher.”

In the entertainment industry, there’s so much more, what you call pilikia [trouble]. They’ll ask as if it’s a challenge or they want you to defend something: “Who said you can?” I’ll say, “Auntie Sieni did!” I throw it back. I don’t mean to do that, but I fool around with them because I want to show them that I do understand. Because I had learned from their auntie, and they’re coming for her.

I don’t want them to forget her. I just tell the younger ones, “You have living relatives from Samoa right here in Chicago. Get to it.” It’s not my kuleana; I learned what I learned of Samoan and Māori and other Pacific music because I enjoyed learning. I tell them, “You are so lucky.” Samoan community is the largest in Chicago, not the Native Hawaiians. And, of all the communities, the Samoan community is the only one that is still teaching their young kids. They all sing and speak in Samoan.

SP: I once had a mentor who said that it’s not so much about identity, it’s about who claims you and who your teachers are.

Lee: Right! Who’s your kumu and who is your kumu’s kumu?

SP: Exactly! You did talk about our kuleana here and in your talk. For those of our audience who don’t know Hawaiian, could you explain kuleana?

Lee: It is a kind of responsibility but it’s at a level where you must take initiative to reaffirm that you are thinking of the critical knowledge in the way that we should be, as our kupuna did.

SP: I ask because, in the Midwest, it’s very easy to see ourselves as very far away from the Pacific. So, what is our kuleana to the Pacific here in the Midwest? How do you see that?

Lee: Put the garbage where it belongs. Stop using single-use plastics. Our waters are affected greatly. You can see signs where the coral reef itself is not happy. I think we need to be behaving as if we are still on the islands. We should consider looking at the Mississippi as another waterway. We need to be thinking more akamai [in relation], get out of the ways that we have been accustomed to and huliau, turn outward, instead of looking in like a huddle. Just huliau and maka‘ala hō, pay attention to what is going on around us and reconsider some of these decisions we would normally make just like that.

We can always make it better. We can be more kind to people. We can be more giving and more accepting. Like with Maui. They need to regrow, and they can do it. They’re experts, and they’ll be eating off their own land, but they need new seed vaults, water purification, because everything was burned. For me in Chicago, it’s to change the way the city views hula. I’m not sure I’ll get anywhere with that, but I’m going to make a gallant effort, and I know that I am faced with having to re-educate from the top of the city working down. There’s no other way.

SP: I really like this idea that in a way, we’re kind of all in a sea of islands.

Lee: Yes. Let’s behave accordingly. Water is life, it’s the source. It’s what we need.