The history and culture surrounding the University of Illinois is unique and full of many interesting topics. Even as a person who has lived in this community for a long time, I’m always learning something new. Ryan A. Ross works at the U of I Alumni Association as the Director of History and Traditions Programs and also stays busy as Senior Editor of Illinois Alumni magazine and Curator and Collections Manager of the University’s heritage museum, the Richmond Family Welcome Gallery. Or as he puts it, “I study the U of I’s past and present, and then I create things, from interactive exhibits and magazine articles to history lectures and other public programming, such as the World War II book event I have coming up in a few weeks with the author Luis Alberto Urrea.” Ross worked with me to share some of his extensive knowledge with a Homecoming history lesson.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: What draws you to stories about the past?

Ryan A. Ross: I’ve always been fascinated to learn about how and why things have changed — people, places, ideas, cultures; really, any part of the human experience — and how those changes have impacted life today. At the same time, I’ve always been naturally curious about my surroundings. When I was an undergrad, that curiosity, combined with my interest in the past, caused me to fall in love with the U of I’s history, and I’ve been studying it ever since. The only difference between then and now is that now I get paid for it!

SP: Is there a specific Homecoming moment or story that stands out to you?

Ross: I’m a sucker for origin stories — the more mythological the better — and the U of I’s Homecoming has a good one. The story goes that on a spring day in 1910, two members of the senior class were sitting on the steps of the old University YMCA (later known as Illini Hall, RIP), talking about their impending graduation and how much they would miss being on campus. They were the 28-year-old Walter Elmer Ekblaw and 23-year-old Clarence Foss Williams, and they decided that they wanted to do “something big” to honor the University.

What they came up with was an idea for an event that would be like “Old Home Week” in New England villages, when former residents came back to their home town for a reunion and celebration. Ekblaw and Williams thought an Illinois football game could serve as a magnet that would get alumni to return to campus, and they would organize related events around the game. They would call the celebration Homecoming.

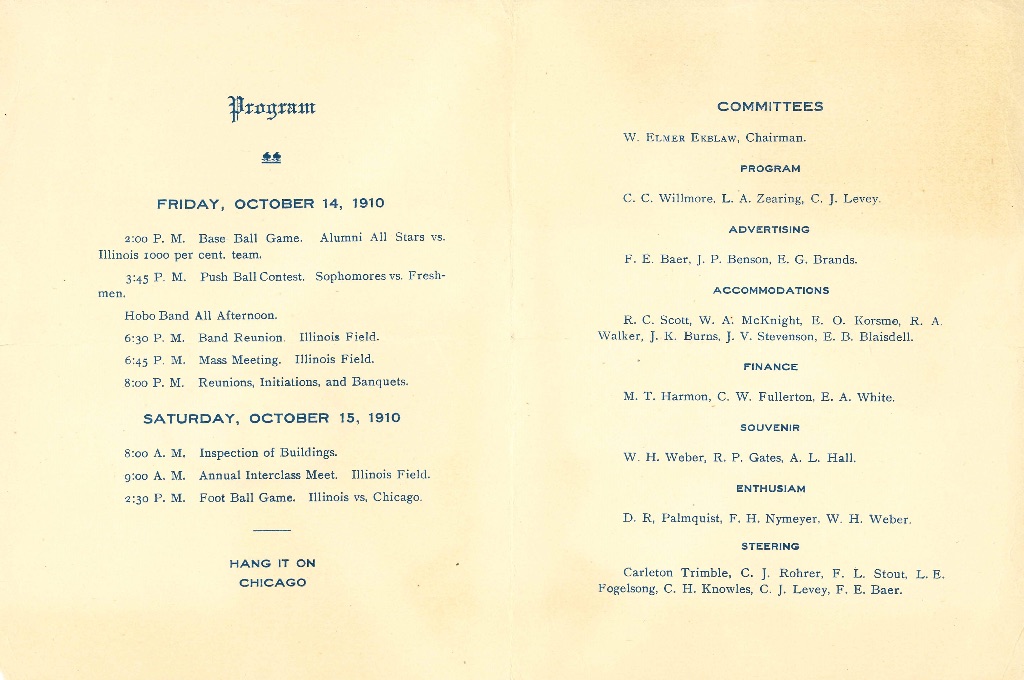

The University’s first Homecoming began on October 14, 1910. It was a joint production of the campus’ two senior honorary societies, Shield and Trident, with the co-founder, Elmer Ekblaw, serving as chair of the planning committee.

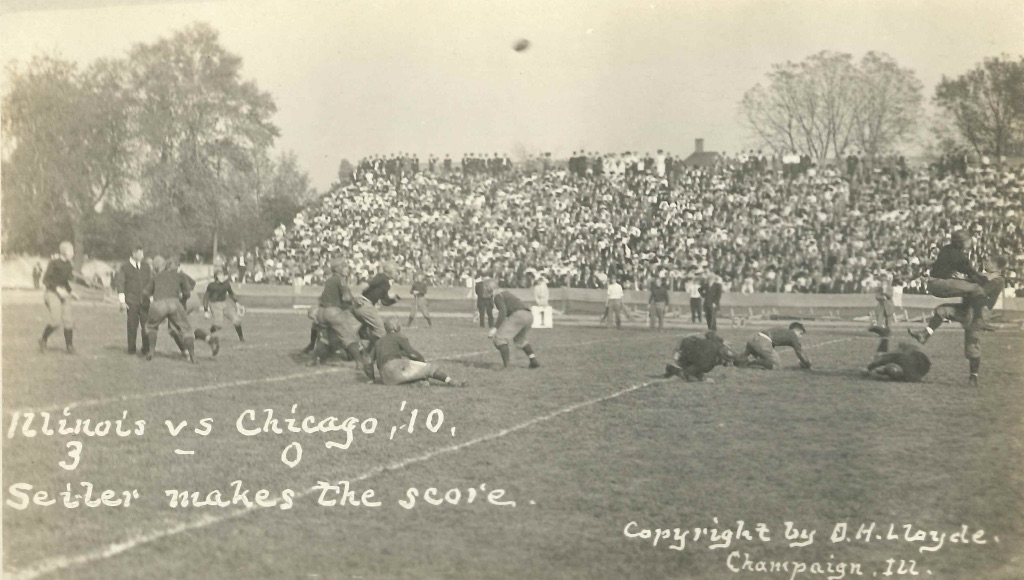

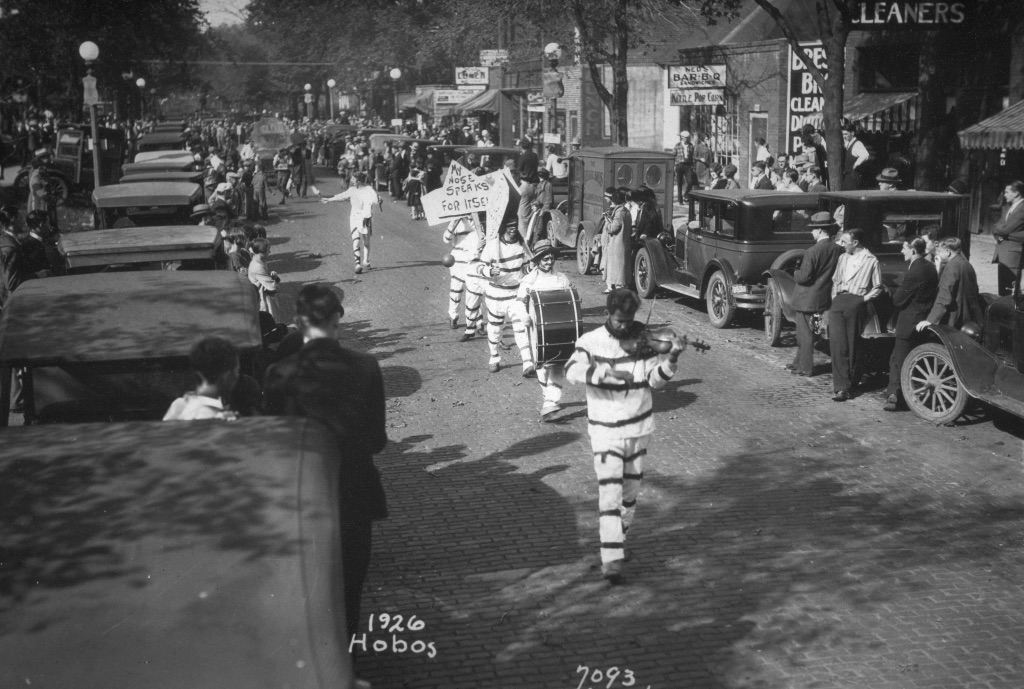

The first year’s program featured a variety of events for returning alumni, students, and the campus and local communities, setting a template for the years that followed. The schedule of events may seem odd to a modern audience, with a base ball game (with “base ball” as two words), an interclass track meet, an inspection of campus buildings (which were decorated with orange and blue bunting), and long-gone traditions such as the push ball contest and Hobo Band Parade (in which participants dressed as hobos and clowns and played musical instruments through the streets of Campustown). From that first Homecoming, a few traditions endure, such as class and organization reunions, and the culmination of the Homecoming celebration: the football game.

The motivating factor behind Homecoming was to bring a large number of alumni back to campus, to reconnect with each other, relive their campus memories, and connect with current students. However, there was already an event on the University calendar that did that: the annual spring Commencement. Traditionally, the Alumni Association had organized class and organization reunions as part of Commencement, and those celebrations were well attended and beloved experiences for returning alumni and current students alike.

Ekblaw’s and Williams’ idea would move those reunions to the fall, giving them their own focus, and ensuring that they were not overshadowed by Commencement. I know this is a surprise to no one, but people don’t like change, and the decision to move the reunions to the fall was a major sticking point for some alumni, who were vocal about their displeasure in breaking from tradition. Some viewed the change as an excuse to sell football tickets and boycotted the event. But all in all, the first Homecoming was a success. Fifteen hundred alumni returned to campus, more than had ever returned for the reunions at Commencement, and the University administration agreed to make Homecoming an annual event.

SP: How have Homecoming traditions evolved and changed over the decades?

Ross: A list of Illinois Homecoming traditions since 1910 might extend from here to the moon! Some, including the football game, the Marching Illini’s halftime performance, the parade, concerts, and keepsake items such as Homecoming football programs and Homecoming pins, took root early and will probably always be part of the celebration. Other traditions, such as formal dances and a Greek house decorating contest, were products of their time and were eventually phased out.

It’s safe to say that one constant feature of our Homecoming celebration has been change. Students introduce a new event one year, like a vaudeville show known as the Co-Ed Carnival (1919), and it evolved into the Stunt Show and lasted for 50 years. But much more often, organizers try a new program or activity, and it sticks around for a handful of years, then falls out of favor. Many of the traditions that take root and flourish in one era will eventually be replaced by the next, ad infinitum.

In recent years, some of the most popular new traditions have been the 5K race; pancake breakfast and fountain dyeing at Alice Campbell Alumni Center; an alumni awards gala; and an outdoor party in Downtown Champaign. Whether those traditions will survive into the 22nd century is anyone’s guess!

SP: What are some traditions specific to Homecoming, and are there any good stories behind them?

Ross: Aside from the traditions I mentioned in the previous answer, one definitely springs to mind, and it’s not an obvious one, like the football game or Homecoming pins. For decades, it was very common for the University to schedule opening ceremonies or dedications during Homecoming. As an example, I’ll mention three, all from the 1920s.

In 1920, the U of I dedicated the Senior Chimes (now known as the Altgeld Chimes) before a massive crowd, and more than a century later, the Chimes are one of the University’s most recognizable and beloved treasures.

In 1923, Illinois opened Memorial Stadium on Homecoming Saturday for its very first game. The excitement over christening the new stadium with a Homecoming game allowed fans to overlook the fact that the building was unfinished, though some fans reported that their seats near the end of the bleachers had no walls or railings to protect them from a treacherous drop. Nevertheless, more than 62,000 fans showed up to watch Illinois defeat the University of Chicago, 7-0, on a very rainy day that turned the field into a swamp.

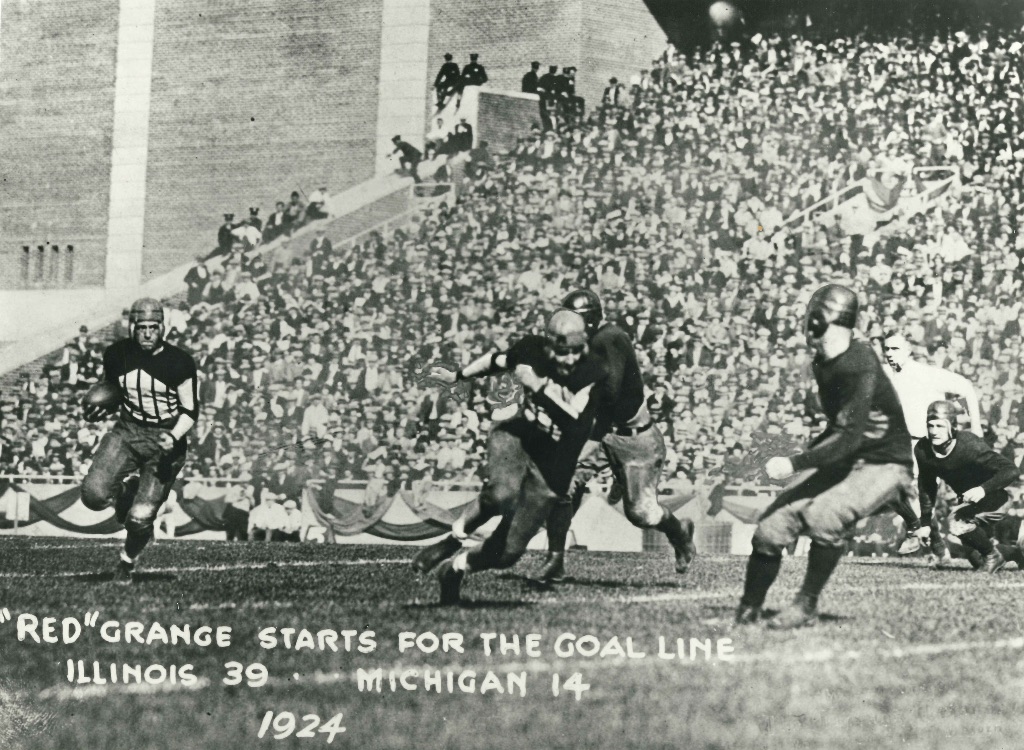

Finally, in 1924, the U of I officially dedicated (the now completed) Memorial Stadium, with a Homecoming football game that became one of the most iconic games in the history of sports. That day, the Illinois halfback Harold “Red” Grange scored four touchdowns in 12 minutes against the University of Michigan, and sportswriters rightfully turned him into a legend. He would go on to become the first big star of the National Football League with the Chicago Bears, and later, he was a member of the University’s Board of Trustees.

I was reminded of this Homecoming tradition of openings and dedications, because this year the U of I is dedicating the new Chabad Center for Jewish Life — another momentous dedication in the Homecoming record books.

SP: There’s a long history of excluding specific groups of people from events like homecomings. Can you talk about the history of exclusion and inclusion, particularly as it relates to BIPOC communities on campus over the decades?

Ross: For much of the U of I’s history, the number of BIPOC students compared to white students has been extremely low. For example, when the U of I celebrated its centennial in 1967-68, the students who identified as Black made up fewer than 1% of the student body. In their low numbers, BIPOC students often felt marginalized on campus and in the local communities, and they experienced overt discrimination from businesses and even in the classroom. In general, that marginalization extended to University traditions, such as Homecoming.

While it’s true that there were a few early instances in which BIPOC students took center stage in the Homecoming celebration, those cases were exceptions rather than measures of progress. I’m talking about things like the crowning of BIPOC Homecoming queens in the 1950s: in 1951, Clarice Davis Presnell, the first Black Homecoming Queen at a Big Ten university; and in 1955, the Korean student Duck Choo Oh, the first East Asian queen. But if you look at the years that followed, those were blips rather than an open embrace of BIPOC students into the University community.

Although University housing had been integrated in 1946, in a social sense BIPOC students remained unofficially segregated from white students for long afterwards and were made to feel like they didn’t belong. BIPOC students felt more comfortable spending time with their own identity groups, and so that’s what they usually did, and still do, to a large extent.

Within that spirit of marginalization and solidarity, in the early 1980s Black students decided to make their own Homecoming celebration, and founded African American Homecoming. The event originally developed out of the step shows Black students began organizing in the 1970s. Over the next four decades, the tradition grew to include a series of events sponsored by the Illini Union Board, including the African American Homecoming Party, Pageant, Fashion Show, and Step Show, which featured a step competition between Black Greek chapters from the U of I and other universities.

The early ’80s also saw the establishment of the University’s Black Alumni Association, which later morphed into the Black Alumni Network, a tight-knit group that offers networking opportunities and cultural programming for its members and scholarships to incoming Illinois students. The BAA/BAN has often held events, including reunions and football tailgates, during Homecoming Week.

SP: Why look back at Homecoming?

Ross: Looking back on any long-running event helps you develop a sense of perspective, to begin to understand where you fit into this continuum of history that we all share. Not only that, but you can also learn a lot about the history of an institution (and the society in which that institution exists), by studying the ebbs and flows of its annual events. Pick a random year, and the details of Illinois’ Homecoming celebration will tell you a great deal about the University, higher education, American popular culture, world events, Illini sports, and a legion of other topics, all coming together to illustrate that moment in time.

SP: Can you give me an example?

Ross: If we look at the 1923 Homecoming, we find an era of major economic growth following World War I, with sky-high appropriations to the University from the State of Illinois. At that time, it’s also becoming much more common for young people to go to college than ever before, and the U of I is in the midst of an enrollment boom. As a result of all that, there’s a building boom on campus, with a new library (now the Main Library) and a new gymnasium (now Huff Hall) in the works. But even more significant, since we’re talking about Homecoming, is the construction of Memorial Stadium. The growing communications industry, and the rise of radio, have turned college football into a national sensation. And the Illinois football team has excellent timing — they win the national championship in 1923, and their star player, halfback Harold “Red” Grange, becomes a household name from coast to coast. Alumni and students are beyond excited to attend the first game at the stadium, and it’s a full house of 62,000 fans, a Homecoming celebration for the ages, with a well-attended parade and pep rally, and local businesses and hotels having one of their most lucrative days of the year.

As a stark comparison, if we look at the 1970 Homecoming celebration, we find a campus embroiled in turmoil. The Vietnam War and other social issues have created a breach between many students and administrators, and annual traditions such as Homecoming have fallen by the wayside. Morale is low. Attendance at football games is down. (It didn’t help that the team is the worst in the Big Ten.) And student protests are up. In 1968, the Homecoming Parade is so poorly attended that the following year, the University cancels it (and it doesn’t return until 1979). In fact, the 1969 Homecoming celebration is so unpopular that the University almost cancels Homecoming entirely in 1970. But it goes on as planned, and it has a distinctly anti-authoritarian flavor. Student participate in their own ways, by creating anti-war house decorations and a Homecoming pin that reads, “When the Boys Come Home,” referring to American soldiers in Vietnam. Everything about the 1970 Homecoming celebration echoes the broader forces that were at work in American society at the time.

Aside from showing us snapshots of the world in 1923 and 1970, those Homecoming celebrations also help to provide perfect illustrations of two universal truths:

- When the Illinois football team is good, and economic times are good, alumni and students care a lot about Homecoming.

- When the Illinois football team is bad, and the world’s in disarray, alumni and students care a lot less about Homecoming.

SP: Anything else you want to tell us?

Ross: Every year during Homecoming Week I hear at least one person say, either in passing or at a podium on a public stage, that the U of I invented the concept of Homecoming. That simply isn’t true, and we have a very enthusiastic Daily Illini editorial from 1910 to thank for that misinformation. Shortly after our very first Homecoming celebration, the DI called Illinois the “originator” of the event, and the story stuck, passed down from generation to generation of alumni, students, faculty, staff, and administrators.

However, in 2005, the historian John Franch definitively proved that other universities, including Michigan, Indiana, Northern Illinois, and Baylor, had held Homecoming celebrations before the U of I. But: none of those events was created to be an annual tradition, as Illinois’ was.

So, while the U of I can’t rightfully say that it created Homecoming, it does have the oldest continuous Homecoming celebration in the nation. Homecoming has been held on this campus every year since 1910, with the exception of 1918, when it was cancelled due to the United States’ participation in World War I.

Finally: Happy Homecoming, and go Illini!

Ryan A. Ross is Director of the University of Illinois Alumni Association’s History and Traditions Programs, Senior Editor of Illinois Alumni magazine, and Curator and Collections Manager of the Richmond Family Welcome Gallery.