“This item is currently under review and is not available to the public.”

A digital stroll through the Archive of Native American Recorded History turns up this phrase more than once. It represents the heart of a multi-institutional initiative to digitize tribal materials and return the rights to the communities from which they were collected.

Returning Native American cultural materials, also called ethnographies (think ethnic, or cultural, biographies), is the goal of the Doris Duke Native Oral History Revitalization Project. Since the $1.6 million initiative’s inception in 2021, seven universities including the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have collaborated with Native tribes in the U.S. and Canada to digitize and return ethnographic artifacts gathered over 60 years ago.

Some tribal members have not seen these materials since the 1960s, when the universities received grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to “collect a robust collection of oral histories from Native leaders … and to return these stories to the tribes and communities that provided them.”

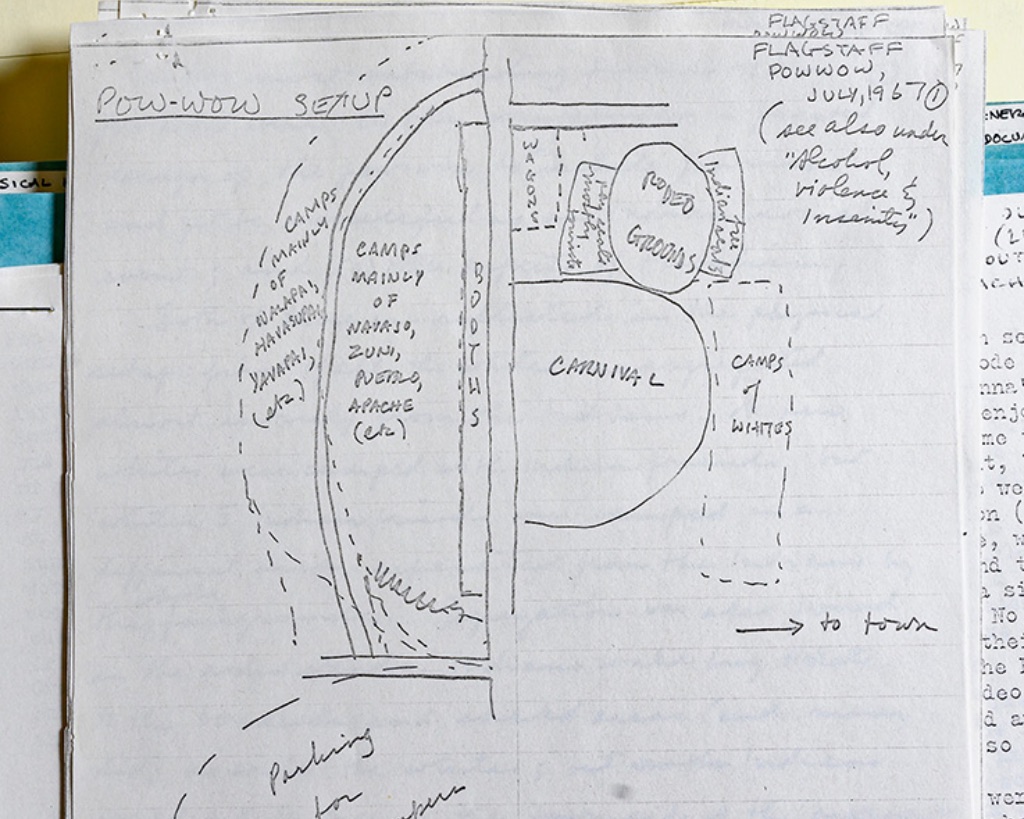

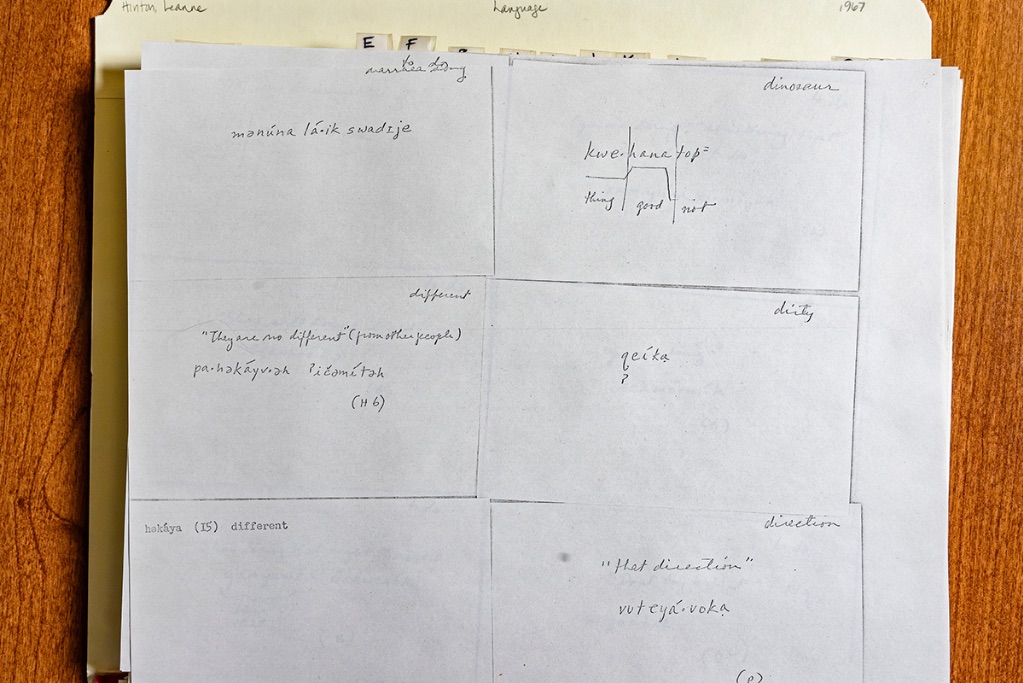

The project’s Illinois iteration centers around researchers in the Department of Anthropology, who lived with and learned from Native communities in and out of the state. Fifty boxes of lived experience from over 50 communities — frozen in photographs, chronicled on film, clipped from newspapers, and scrawled in field journals — were the result of their efforts. Altogether, the universities’ combined materials encompassed over “150 Indigenous cultures.”

Now, the universities originally tasked with collection are on to their next charge: to digitize and return. Materials are made available to their original owners (or relatives thereof), who determine their suitability for public access. This practice acknowledges the materials’ “tribal sovereignty,” a term used by Bethany Anderson, a member of the project’s U of I branch and the natural and applied sciences archivist for the Illinois Archives, as quoted in a recent press release.

Shareable materials will be housed in the online archive, which is searchable by keywords, media type, and community of origin. According to the site, “all sizes and types of institutions, Native and non-Native, are invited to apply to participate.”

I spoke with project leader Jenny Davis, an associate professor of anthropology and American Indian Studies at the U of I, the director of the American Indian Studies Program and co-director of the Center for Indigenous Science, and a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. Christopher Prom, the associate dean for digital strategies for the University Library, is also a project leader at the U of I. Courtney Richardson, a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Information Sciences, is involved as a graduate research assistant.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity..

Smile Politely: I’m interested in the word ‘revitalization.’ How is this project bringing something back to life?

Jenny Davis: These recordings and these materials have been closed away, hidden away in boxes since the 1960s. They were sorted and cataloged when they were transferred to the university’s archives, but they haven’t been engaged with — they haven’t had much of a life. Part of this project is reconnecting them to communities so they get to have a life again. There are community members listening to these songs and hearing these voices, so the materials themselves literally get to have a new life. And the connections that community members are able to make with them are their own kind of revitalization, too.

SP: How did you become involved with this project?

Davis: I work with language revitalization in my own and other communities, and part of that work involves finding which parts of our culture have ended up in archives and museums and trying to get those back to their communities of origin. Whenever I go to an archive, I automatically look for my community in the catalog — I’ve been doing that for about 20 years now. Knowing how important these materials are to their communities, I became interested in this project from that perspective. I do a lot of repatriation work in my role on campus, as well.

SP: Repatriation is a term that has come up frequently as of late, especially in the context of museums and institutions. How do you define it in the context of this project?

Davis: Most people conceptualize repatriation as a physical return, where the tribal communities and their direct descendants get to decide what happens with their materials and collections. Quite often, that does mean a physical return, but sometimes it means a reburial or a rehousing. It can also mean an agreement, where the materials stay at the institution they’re at or where permission is given for them to be part of a research project.

Conceptualizing repatriation as the return of control is really the key thing to keep in mind. Part of it may involve the actual materials — or copies of the materials — going to communities. Ultimately, it means that the communities decide who has access and how materials can be used.

SP: Repatriation and revitalization are both more abstract elements of your work. What does your day-to-day work for this project physically look like?

Davis: It really depends on the day. Most of it is conversation, checking in and getting feedback over email or Zoom. It involves reaching out to the communities and letting them know what we have, and inviting them to be a part of the co-curating process. It also involves making sure they have access. Usually, communities will select two to three point people that we’re working with, and those people will be working with elders, knowledge-keepers, and other community members. Sometimes, the decision is that no one outside of the community should have access to a given material.

SP: Have any particular conversations or anecdotes resonated with you so far?

Davis: There was a really beautiful moment where one person working with the materials recognized the name of her grandmother on the list of books that were recorded. She got to listen to the recording of her grandmother, and actually remembered the anthropologist having been present, recording, when she was a child. For these communities, it’s not an abstract, intellectual project: these are their family members, these are their songs, these are their cultural traditions and the histories of the people they know. So that was a moment where we thought, “This is why we’re doing this. This is why it’s important.”

SP: Lately, institutions, museums, and universities are reevaluating how to archive and collect in an equitable way. Do you see this specific project fitting into that conversation?

Davis: It’s a great example of how pervasive the practice was of going and collecting things from communities with no intention of ever returning them, and not being seen again, right? So, it’s an attractive method. You just show up, you record things, and then you disappear and the community never hears of it again. One of the things that’s exciting is that this is an opportunity for relationship-building and for moving forward. So now, moving forward, we are in conversations with these folks in a sustained conversation. So rather than losing something or giving something up, this kind of work is actually really generative. It creates opportunities for research. It creates opportunities for connections with people, whether they are scholars in the tribal communities, or whether they’re potential students or faculty.

SP: What opportunities does this project create for UIUC as an institution?

Davis: When we think about something like repatriation, one of the places that it’s discussed most robustly is through the requirements of NAGPRA [the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act], which is federal law. But archival materials, ethnographic and linguistic materials, oral histories — those kinds of collections aren’t covered by that law. And so there’s actually no kind of mandate from above that says you have to collaborate, or repatriate, or co-curate, or give that control back to the tribes. And so that’s not necessarily the norm for most institutions. And so I think that any time we have the opportunity to not ask what’s being required of us by federal law, or what’s being required of us by state or even university policy, we can instead ask what’s the best, most humane, most generous way to approach these collections.

SP: Is there significance in the specific history of this campus and community?

Davis: The specific histories of the University of Illinois and our state are always important. We are what I like to phrase as a “removal state,” which means that all of our tribes were removed by the federal government to other states. That means that our relationships with Native nations, to the extent that we have them, is at a distance — partly because of that removal history, and partly because of the university’s history with a Native mascot. I’ve met a lot of people who, to their knowledge, have never met a Native American before, and who rely on media representations and stereotypes of Native Americans to even imagine what Native people look or sound like. These kinds of projects are about actual living Native people, actual Native cultures, and the diversity of Native cultures. And so I think that anytime we have the opportunity to remind folks of that, for people to see and experience that firsthand, is really important in a state like Illinois.

SP: After two and a half years, this grant is set to wrap up in December 2023. What do you want people to take away from the project?

Davis: I think on a really basic level, we have responsibilities and opportunities as an institution, and as a community, to be attentive to the kinds of collections that we have and to the histories that we’ve been a part of, and to respond to them. I think we have opportunities to always be growing, and striving towards those best practices and thinking about what they look like and to really understand them as positive and generative rather than some kind of tedious obligation or something that is keeping us from doing something else, because that is actually the important work.

And also, that we don’t exist for the intrigue and interest of others. Even if it’s academic or intellectual curiosity, that’s not actually why we exist. Those approaches that prioritize that kind of information or that kind of interest, and that don’t prioritize us as living humans who could be collaboratively engaged with, create archives that sit in the dark for 60 years.